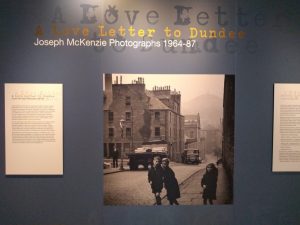

A Love Letter to Dundee: Joseph McKenzie Photographs 1964-1987

To shout ‘I love you’ from the rooftops seems such a 70’s thing to do but that’s exactly what one student living in Dundee’s Hawkhill did for his girlfriend around 1970. Joseph McKenzie (1929-2015) immortalised the romantic gesture in a black and white still that inspired the title for this exhibition. The student painted his declaration on tenement slates and McKenzie captured the moment, just as he did with so many elements of everyday life in the city from 1964-1987.

To shout ‘I love you’ from the rooftops seems such a 70’s thing to do but that’s exactly what one student living in Dundee’s Hawkhill did for his girlfriend around 1970. Joseph McKenzie (1929-2015) immortalised the romantic gesture in a black and white still that inspired the title for this exhibition. The student painted his declaration on tenement slates and McKenzie captured the moment, just as he did with so many elements of everyday life in the city from 1964-1987.

The two photo essays, entitled Dundee: City in Transition and Hawkhill: Death of a Living Community, aim to take visitors on a contrasting journey through the city’s past from the perspective of a master-photographer. Born in the East End of London and evacuated to Dorset, McKenzie was no stranger to hardship and developed deep empathy for those  living in deprived communities. This was evident from his 1960s Glasgow study, Gorbals Children, inspired by the paintings of Joan Eardley and reminiscent of similar portrayals by Bert Hardy in the 1940s, as well as the psychologically penetrating imagery of working class children produced by Edith Tudor-Hart in the mid 1930s.

living in deprived communities. This was evident from his 1960s Glasgow study, Gorbals Children, inspired by the paintings of Joan Eardley and reminiscent of similar portrayals by Bert Hardy in the 1940s, as well as the psychologically penetrating imagery of working class children produced by Edith Tudor-Hart in the mid 1930s.

In 1964, McKenzie became Head of Photography at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and began to chronicle the conditions Dundee’s working class. The ‘father of modern Scottish photography’ produced a series of documentary prints, full of subtle grey tones and black areas, conveying meaning and sensitivity for his subject. His cameras were loaded with slow film, rendering the range of tones possible and capturing detail to create that ‘decisive moment in time’, drawing contemporary viewers into a by-gone era. As to his development techniques, former student Calum Colvin described him as a ‘darkroom alchemist’.

McKenzie’s ‘love letter’ begins with the end of the line for Dundee West Station, where the enormous wheels of a steam locomotive are set side by side with the tragic destruction of the grand Victorian facade. Fireworks later burst over the Tay Rail Bridge to mark the opening of the Tay Road Bridge. where McKenzie’s images expose us to the processes and expressions behind construction. Beside shots of the ‘Abercraig’, author Jim Crumley echoes this, writing that the Fifies ‘let you become a moving fragment of the Tay itself’ and laments how much he missed the little ferries.

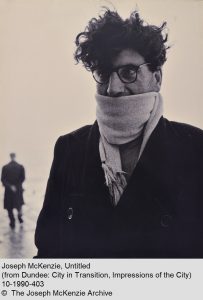

The harshness of bridge building is realistically portrayed but McKenzie’s angles allow the viewer to connect with the faces of workers, and the sweep and curves of the design. Later, the bitter chill of the north-east climate leaps out in one particular photo of a slim, young man with heavy-rimmed glasses and woollen face-covering. This precaution against the cold marks an uncanny connection to the present-day covid crisis for me. Cheeky street children and bairns falling out of prams, remind us of Hardy’s style, but his later ‘gangland’ shots of the Lochee Fleet and the ‘death of a living community’ photographs bear a resemblance to Oscar Marzaroli’s images of Glasgow also under the same sentence.

The harshness of bridge building is realistically portrayed but McKenzie’s angles allow the viewer to connect with the faces of workers, and the sweep and curves of the design. Later, the bitter chill of the north-east climate leaps out in one particular photo of a slim, young man with heavy-rimmed glasses and woollen face-covering. This precaution against the cold marks an uncanny connection to the present-day covid crisis for me. Cheeky street children and bairns falling out of prams, remind us of Hardy’s style, but his later ‘gangland’ shots of the Lochee Fleet and the ‘death of a living community’ photographs bear a resemblance to Oscar Marzaroli’s images of Glasgow also under the same sentence.

In the Hawkhill collection, McKenzie documents the decline of major Dundonian enterprises, like Cox’s Camperdown Works and the legendary Wallace Pie Shop in Hawkhill. Bleak landscapes reminiscent of the Clydebank Blitz sit alongside beehive hairdos, gossiping women, nimble weavers and cool students on motor-cycles, scooting through the centre of the university hub. An STV documentary, produced in the same period, gives visitors the background to these changes and residents’ hopes for a brighter future, but like countless other love stories, McKenzie’s photo essays are poignant reminders of the twists and turns in the ever-evolving life of a city.

In the Hawkhill collection, McKenzie documents the decline of major Dundonian enterprises, like Cox’s Camperdown Works and the legendary Wallace Pie Shop in Hawkhill. Bleak landscapes reminiscent of the Clydebank Blitz sit alongside beehive hairdos, gossiping women, nimble weavers and cool students on motor-cycles, scooting through the centre of the university hub. An STV documentary, produced in the same period, gives visitors the background to these changes and residents’ hopes for a brighter future, but like countless other love stories, McKenzie’s photo essays are poignant reminders of the twists and turns in the ever-evolving life of a city.

This exhibition is no ‘Jam, Jute and Journalism’ portrayal of Dundee’s past; instead it illustrates how change and progress can drag a city into the future with no real regrets, only to mourn its passing many decades on.

I remember my mum, Gran and I going to see this exhibition in 2000. There was a photograph of my Grandad in it. He was a Railway worker and the photograph showed him standing face on covered in soot. I think their might have been an opportunity to buy but my Gran didn’t want to as he was always very “dapper “ and the photograph didn’t represent him. I just wondered if the photograph was still part of the exhibition, where it was and if it was possible to see it.

You might try asking the McManus gallery curators? Think the exhibition has ended…