The Saints Are Coming

a line of curses, promises, demands,

wishes, intoxicants and offerings […]

sets all the prayers in the house to glint.’

(From ‘Vespers’, All The Prayers In The House, Miriam Nash).

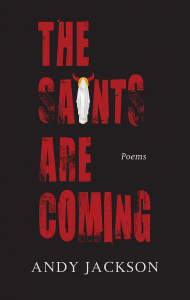

Having grown up in the Catholic faith, courted by pictures and other icons of the tradition (usually from a shrine shop in Lourdes), I was no stranger to the oft-heard invocations to saints, for example, as intoning prayers to St Anthony, patron saint of lost small things such as purses, housekeys, shillings for the meter in my grandmother’s case. There were others but none who could transform lives by throwing a bingo win in with the found items like this saint. So it’s with delight that I have in my hands, Andy Jackson’s third published collection of poetry, The Saints Are Coming, his first with Blue Diode Press. This title treats readers to a shining hagiography of saints for this anthropocenic age who, with due diligence, watch over the livingness of poets, radiographers, lottery winners, thieves, radicals, embroiderers, haemorrhoid sufferers, gamblers et al.

Observe as prosecutors

rearrange denials into damnations,

transmute honesty into culpability […](‘The Catechism of St. Catherine of Alexandria Patron saint of jurors‘)

These saintly characters cast in malleable forms, sometimes enacting the ludic virtue of a Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-in ‘watching as I die my thousand/deaths, still clinging to my shtick’ (‘The Martyrdom of St Lawrence Patron saint of comedians‘) while at other times the gravitas of a rebel drama, are resolute in their capture of the tones and cadences of their patronage:

A rebel’s not a rebel till the firing of a shot.

Plebiscites are binding till the rope begins to rot,

and nobody is feared for the things that they are not. […](‘The Chorus of St Baudilius Patron saint of radicals’)

How they fuse thoughts and feelings in the creation of dialectic and by these means gain access to the readers’ imaginations, to our personal dramas, keep us in thrall to their every intersection with common experience, and every whispered vesper.

Nacreous is ‘The Vision of St Joseph of Cupertino’ in which astronauts must furl their ‘wings’ and recalibrate, with the weight of what they’ve seen, for air:

gift will be to see things as they really are;

[…]

darkened pockets of existence where the power

dims and dies at night, a vague pod of whales

beyond the melting reef[…]

but as your flesh accepts its proper mass again,

the world will hang like boulders on your back [.]

The poet has plenty of axe to grind in ‘The Beatitudes of St Bernardine of Feltre Patron saint of bankers‘, and does so with the candour of a Steve McQueen (British film director), name-cropping sinners as he goes:

Blessed are the short-sellers,

for they reveal the weakness of the world

by leveraging their souls.[…]

Blessed are the analysts,

for the bear shall lie down with the bull

at the final closing of business….

This poetry feels political―a fountainhead of energy.

‘The Canonisation of St Brigid of Kildare’ is almost a villanelle until it rhymes out of line and energy as ‘The old nib trickles/ its last drop, shrivels/and dies’ wryly summing up what posterity has in store for poets for whom death has dried up any residual hope for more.

Revelling in a pantoum is ‘The Chant of St Edmund the Martyr’, whose interwoven prayer mimics the mutational habit of the Coronavirus, in which the first and last lines repeat as a chilling reminder of ‘what goes around, comes around’. Fragments of language that have been an intended part of the poem’s formal integrity, pop-up with the seeming randomness of ruderals in other poems, seeding the landscape with ‘dims’ and ‘dies’… just as a virus might infect others.

How are these saints coming? Loudly and unanimously singing, shouting, disclaiming? Glimmeringly with truth? All of this.

Leave a Reply