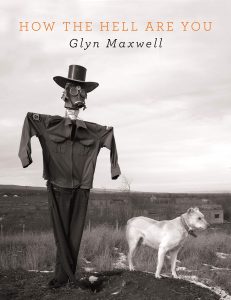

How the Hell are You

It is not the question of How the Hell are You, but rather the question of

It is not the question of How the Hell are You, but rather the question of

who the hell were we

(‘How The Hell Are You.’)

that encapsulates Glyn Maxwell’s most recent poetry collection of the same title. Maxwell has won many awards for his poetry and has been previously shortlisted twice for the TS Elliot Prize. However, this collection sounds a darker tone in his poetic oeuvre. It concerns the nature of our present world and how time has the ever-menacing tendency to slip out of sight. It is poetry from all walks of life, whether that be a sonnet from artificial intelligence or lost poetry about private dwellings. The collection also gives way to reflect on the form of poetry itself, looking back to critique what it was and what it has become.

Thus, we get that peculiar title, How the Hell are You. It brings you to the centre of a collection of poems that may not be meant for your eyes, only for the speaker to then turn around and ask why you are here. The “you” on the outside of the book is both a stranger and also someone of some significance to the speaker, in a relation that has not been named – perhaps the role of the reader; both passer-by and confidante:

Two creatures with no history

who dreamed it would be otherwise but

who the hell were we.(‘How The Hell Are You.’)

Maxwell is concerned with our relationship with time and our need to worry over the ways in which we spend it.

You ask me what I do

and I say I’ve no time for you,

you make small talk with me,

you make it with eternity.(‘Small Talk With Time.’)

In repeating this stanza, Maxwell shows the cyclical nature of time. Whilst we may ponder and become lost in the thought of running out of time, to focus too much on it is to lose it faster.

Other poems in the collection seem as though they have been picked up out of time. They are often dedicated to other people, as if the reader were not meant to see such an intimate creation. For example, ‘Seven Things Wrong With The Love Sonnet’ is dedicated to ‘Anna’ and criticises traditional love sonnets written as private confessions of one’s feelings for another. For these to be published figures an intrusion on such relationships.

It’s planned – we weren’t. It’s structured to unfold

in a set time – we haven’t and we shouldn’t

It lets no silence in – we do and share it.

Maxwell comments on the flaw of modern-day posting. We share, we tweet, we open up these private moments in hope for those blessed 15 minutes of fame. However, he notes that this is not a new problem, the history of love sonnets —how they made their rounds long before internet was at our fingertips — is a case in point. It is perhaps human nature to gossip but what right do we have to break down these lines, and create our own meaning when it was not meant for us in the first place?

Throughout the collection, Maxwell’s tone is very bold, blunt, but also arch at times. There are no any grand observations for the reader to think over, but rather that his words come from somewhere within. He knows more than us. It is here we see how he views poetry as ‘truth-telling’. Maxwell wants the reader to understand that whilst we may view his works as pessimistic, someone must show us the truth of our natures.

Leave a Reply