Ekphrasis

From Wiktionary:

“Ekphrasis”, from Ancient Greek ἔκφρασις (ékphrasis, “description”), from ἐκφράζω (ekphrázō, “I describe”), from ἐκ (ek, “out, ex-”) + φράζω (phrázō, “I explain, point out”).

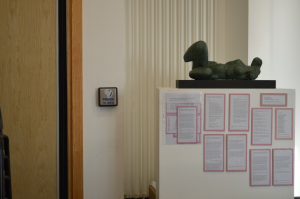

Here are five pieces from a call to respond creatively to a sculpture (circa 1995) affixed very securely to a plinth in the creative writing room at the University.

Invitation

That’s a bit rude is it no?

What is?

That green statue thing over there.

Ah, that’s not a statue, that’s a sculpture

Aye? What’s the difference?

Well, a statute is a life-size depiction of a person whereas a sculpture is three-dimensional art.

Art, aye? Ye mean like a painting?

Well, yes. Sculpture is a different medium. Looking at a painting is an entirely different experience from viewing a sculpture. Sculpture is an ancient art form. It was used to show respect for the gods and religious icons. Sculpture uses solid matter to highlight aspects of the world, our place within the world, our explorations of the world.

I dinnae get it, I mean, there’s mair tae see in a painting.

Well, that depends on which kind of painting, what the artist is communicating, the context.

Aye, right.

This particular piece has been formed from terracotta and then glazed.

Is that how it’s aw green?

Yes. That’s the glaze.

An it’s, terracotta?

Yes.

So, if I geen it a chap wi a hammer…

Well, that would be a shame.

How come?

Well, because it would be destroyed.

Looks like somebodies awready had a chap at it. Look at it, its nae heed.

I don’t understand.

What’s no tae understand? Heed, napper, bonce.

Oh! I see! Head.

Aye, Heed. Cause that’s what I cannae understand? How does it no hae a heed? Or erms? And only half its legs. Hers.

Well, it would appear that the sculptor wishes us to focus on the female form. Modern sculpture is an individual expression or exploration of what we take for granted, so perhaps this is what he is drawing our attention to, the beauty of the female form.

The beauty of the female form? Whua fir? Men?

Goodness, no! For all who wishes to view it.

So how’s there bits missing, then? And how is it, the way her legs are open, I cannae help but look at her bits, and I’m a wifie. It’s embarrassing. It’s like she’s just a lump o meat. Fair enough if she’s nae erms or legs, but she should at least hae a heed. Or have the legs and erms been removed tae make her helpless? And come tae think o it, how no just chap her legs aff aw the gither? Or wid that gie ye the boak? Are the thighs half open tae gie ye an invitation? It widnae be the same withoot them, wid it?

Well, I don’t think, I eh-

No. Ye dinnae. Is that the “ye dinnae look at the mantlepiece when yer poking the fire” scenario? Dae women no need heeds, like? Is a heed no part o the female form?

© Wanda Macgregor

***

Reclining Torso

Terracotta, green patinaed,

ancient bronze (seemingly)

she lounges. Head, arms

and feet hacked off,

legs spread open,

pried a little wider still

by hungry eyes, skin—

the texture of goose bumps.

A limpid invitation?

But really, it’s merely

a fine art labial opening.

No feet to run away

no arms to hold close

or fingers to caress, no

expression of pain

or orgasmic moan

(she’s headless after all).

Just someone’s come-

fuck-me poke hole;

a wet dream dredged up,

skewered in the mind,

enshrined atop a plinth.

Who, I wonder, put it there?

© Gail Low

***

Confined in an upside-down tumbler, its spindly legs are stark black against the white paper. Distorted and magnified by thick glass, it is trapped, and the wild fear of capturing it now a forgotten frenzy. She wonders exactly where it was planning to go and shudders to think where it had been. Taking a few moments to look closely, her heart rate settles. She stretches out her hand before her, making sure it is steady.

Picking up the tweezers, she keeps an eye on it. No longer scurrying, it is dead still but not dead. She moves her left hand on to the glass and begins to tilt it creating a slight gap between the paper and the rim. As quick as a blink it jerks and halts back into a freeze frame. Slowly, with her right hand she slides the tweezers through the widest point. Accurate and quick, she remembers she is an expert eyebrow plucker. She edges the sharp blades of the tweezers towards one of the eight legs that juts out towards the centre of the glass.

You have to be exact before you snip the pincers. You can’t miss.

GOT IT.

There is a blur of movement as it spasms and contorts at speed around the inside of the glass. She pulls the leg towards her and once the body nears the rim and the metal tongs are fully outside of the glass, she slams the tumbler down and yanks hard. Leg clean off. It flurries about in a crazy ramble before placing its remaining legs up the wall leaving a few on the paper. It stiffens back into stillness, retaining its silence. She sits back in her chair. Lifting the tweezers to the light she studies the bodyless leg. Lifeless and unremarkable, like a plucked hair.

Slipping the silver pincers back under the tumbler she moves them in slow motion until she reaches the next leg. Each pluck brings the same response until the fourth. The abdomen droops onto the paper causing it to sit lopsided. She is repulsed by its vulnerability. By the time the fifth limb is pulled off there is no more fight.

Game over.

After the last leg is tugged from the shrivelling body it resembles a thumbnail sized clump of dirt muddying up the bright page. Disappointed, she lifts the glass and sets it aside. Tipping the tiny torso onto her windowsill, she leaves it there like an ornament and realises it wasn’t the spider that she was afraid of but its legs.

© Victoria Lothian

***

I lie there flat on my back, flailing like a beetle upended. I struggle to right myself but my legs slide on the hospital tiles and my hands claw the floor ineffectually, too weak to lift the weight of my own body. I stop trying and stare up at the strip lights. Cold creeps through the thin fabric of my gown numbing my back where it meets the hard floor. I hear a chorus of voices shouting for help. Nurse! Nurse! An alarm erupts in a shrill wail and I wait.

It is quite an experience to fall so hard it knocks the wind out of you. I recall an over-ambitious dive from a bunk bed as a child, an ill-advised ride on a friend’s skittery horse as a teenager, the numerous stumbles that have increased with passing years as limbs swell and drag and refuse to cooperate. And now this.

Admittedly, there’s a brief delicious space to it, after you land.

An unbearable terror accompanies the preceding moments as you feel your footing slide and you eye the surface coming up to meet you, envisioning the impact on your body as it hits.

There is a visceral tension as time slows and focus narrows; eliminating everything but this one concern, to avoid the inevitable.

But the immediate impact offers an incredible release, if you can remain alert to it. All struggle is suspended. The moment your body meets the hard surface, you are freed from the agonising responsibility of preventing this awful thing from happening. It has happened.

Immediately before the physical sensation of pain rips through the body, there is one precious second where the breath is forced out of the lungs in a single violent expiration and, scrambling to decipher sensation and information, the mind wears itself out. For one beautiful second, it rests like a stopped clock.

For one beautiful second, I rest.

Until then the pain registers, thoughts regain their hold and the awful struggle begins again.

© Collette Cowie

***

The Sculptor

The sculptor does not know that we are here—

might guess in quiet moments,

then twist away mistaking us for doubt.

Nobody notices our twitching toes

in lonely warehouses at dawn

or hears our fingers crack in dark museum halls.

Human bodies do not hear the magic in their art—

it hums a possibility to bind or free,

or blind or see, or manifest the unexamined,

ill-formed parts as faithfully

as any truth a body awestruck, apprehends.

Know that bodies will complete themselves if left unformed.

We are the knees you severed,

too enchanted with the thighs you wrought,

we hold the gaze you couldn’t meet, so didn’t make.

We converse, confront with lips and minds,

ideas and expressions feared

by calloused hands that trace dismembered counter-parts.

Do we miss those swelling curves, that vaulting charge?

Erotic reverence in form, that flesh of stone? Of course.

They are our birth-right; we are beauty invert, they are us.

Do not deceive yourself; you know

those bodies are ours;

we will return to them.

© Ellie Julings

Leave a Reply