Life Without Air

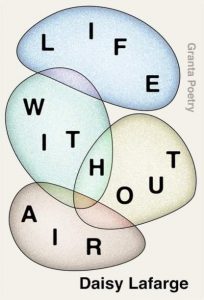

Daisy Lafarge’s debut collection Life Without Air shortlisted for the T.S. Eliot Prize, is the ferment of a busy mind drawing from Louis Pasteur’s process of fermentation. Like the intersecting cells on the jacket, suggestive of their proximity, seven sections explore the complexity of human and ecological co-dependence,

The inaugural poem, ‘Meridian Dream’, sits title-less and centre page in a single section. Three quatrains open with the titular refrain ‘meridian’ from which an anagram is formed in the proceeding lines, a spontaneous generation of meaning:

Meridian

I dream in

I rid name

I mend air

Meridian

Marine id

Né midair

I drain meMeridian

I’m in dear

Mired in a

Mined air [.]

There is an energy which flows through these lines as the syllables of the root words re-form, in a dichotomy of wistful freedom and churning toxicity. The gentle humming consonance of the ‘m’, and the sighing assonance of the ‘a’ and the ‘e’, leads us into a false sense of sonic security until these elements bind with our semantic understanding. Like air, these words evoke the intangible, for to be ‘mired’ is to be stuck and the toxicity of ‘mined air’ is invisible, and it is from this that Lafarge encourages us to consider the complexity of our interactions with each other — ecology, atmosphere, stratosphere and beyond ― in air and, in airlessness.

In ‘axiology’ the underlying theme of the title is juxtaposed with a theme of infidelity, a concept that we feel before it becomes conscious. The betrayed speaker, world collapsing, awakens to ‘the grating wrack of a mechanical sun/it was ticking on its side’. The clue is in the line: ‘from the too-soon moon’, an allusion to The Water Boys track, You Saw The Whole of The Moon and the bigger picture is exposed as it [the moon] is: ‘flung up in its [the sun’s] place and held/ there in cuckolded sky […]’. Here Lafarge’s aural play is demonstrable with harsh ‘k’ plosives set against the wailing assonance of ‘green’ and ‘Verdigris’ and ‘screeched’, creating a maelstrom that validates rather than values a toxic relationship.

‘Dredging the Baotou Lake’ explores the human paradox of rare mineral mining for green technology, delivered in a ten-poem sequence. Neat couplets inhabit the page in ‘The pipework of CERN’ where: ‘[…] they understand that sometimes/you have to be your own knife/[…]’ the sharp edge later chiming from within in a single word: ‘nihilism’. This is a stark contrast to ‘Matter’, a lyrical couplet that stamps the message home with its metrical feet:

as with the moon, so with our mothers

it is what we make with the fallout that mattersLike air, its resonance perfuses the blank page beneath.

In ‘understudies for air’, a further sequence of ten poems, Lafarge urges us to look for what remains unseen but is, yet, visible. Take ‘Falsification Air’:

[…] consider the sheets of air

gridlocked in double glazing. now

are you beginning to understand?

In ‘Gaslit Air’, the ominous tone of the title seeps–insidious–into the lines: ‘I was told to conduct my body like an hourglass’ and ‘soon I became one with my public face’. The title invokes images of the industrial, the environmental-yet all remain, in this instance, toxic.

In the titular poem, ‘Life without Air’, there is much to consider as the speaker declares:

Empedocles was a woman

in a sex of natural disasters [.]

I have spent some time peering into this poem spanning three pages like the ‘rim of the crater’ into which the philosopher is said to have thrown himself. Here, human relationships and ecology converge as we learn:

Exhaling with fumarolic dissent

that to be in your element is to die in it.

Like spontaneous bacterial growths, Larfarge’s observations take us on a mutational journey of understanding which resonates so strongly right now — the creation of liminal spaces that morph into heightened awareness.

Leave a Reply