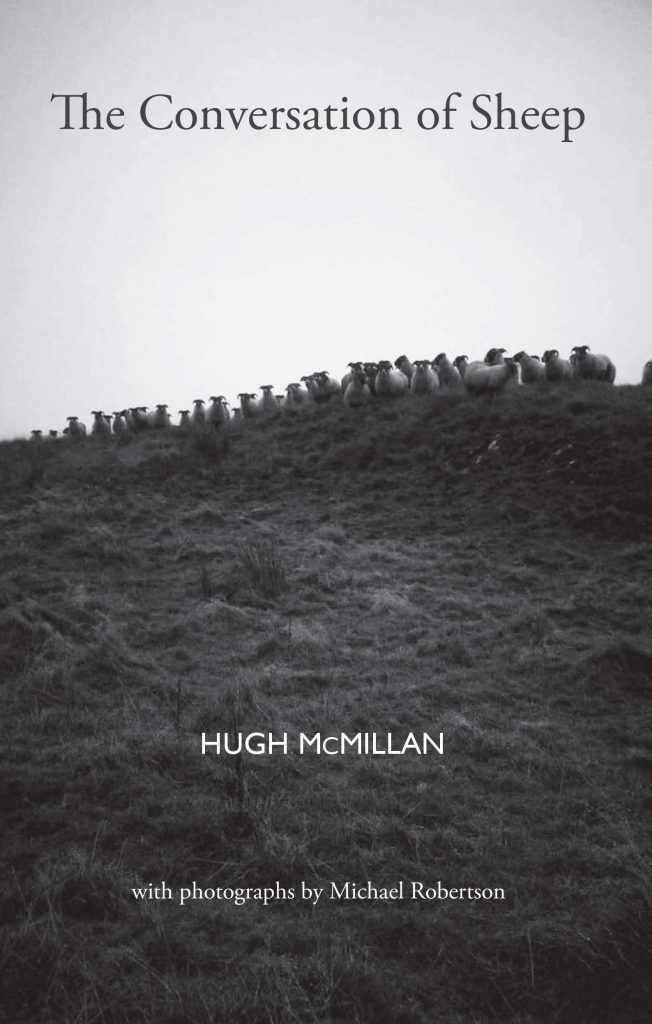

The Conversation of Sheep

Hugh McMillan

(Luath Press, 2018); pbk £8.99

I’ve never read a poetry book that has made me laugh out loud the way Hugh McMillan’s 2018 collection did (it is possible I’m reading the wrong poetry). But The Conversation of Sheep is more than just sheep jokes, and therein lies its brilliance. The artistry and rhythm of these short, mostly page-long poems is contemplative and slow, but their content is incisive and witty, with pathos hanging over everything like the mist in the photos that accompany them.

The first thing to belie the humour, and possibly the reason I was so surprised to find myself laughing, is the somewhat menacing black and white cover photo depicting the silhouette of a herd of sheep on a low hill. The monochrome contrast recalled for me first world war imagery, as if the sheep were climbing from the trenches in a last attempt on the front.

Each poem in The Conversation of Sheep is paired with a with black and white photograph by Michael Robertson, a farmer neighbour of McMillan’s. These are, if I am not mistaken, real photographs, the kind made with film in a dark room. They are grainy, shadowy and evocative and are carefully curated alongside the poems. One double page spread arranges an image of sheep standing atop a deep peat cliff alongside ‘Sahil Island’, a poem spoken by the prehistoric souls now preserved beneath ‘this casserole of soil’. The image gives the message roots; the poem wouldn’t be the same without it.

Describing the genesis of the book’s titular poem on the Poetry Library website, McMillan begins by declaring ‘I live in a depopulated area’. Not isolated or rural but depopulated. The undertow of this collection is lament:

Dykes twist to the horizon.

Where are the men who built them?

Gone to Nova Scotia

With their pipes and neckerchiefs.

I’m reminded of Pete Seeger’s famous anti-war song here, and McMillan himself references heartbroken traditional songs in ‘Simple Truths’, a subtle but weighty reflection on the pain wrought by colonialism on the disenfranchised and displaced.

The sheep, those ‘stoic punctuation marks’ are what remain. And their indifference and ulterior preoccupations are what punctures the gravity with humour.

What a burden to be the most common noun in the bible

after Lord, God and Israel

and yet not have a single speaking part?

It’s bad enough being used for food

but metaphor is worse.

Funny as they are, these lines do not amount to the punchline of this poem about sheep reclaiming their place in the Christian canon, nor is it the best gag in the collection – I wouldn’t do that to you. McMillan’s jokes are surprising; they jump out at you from behind quiet ruminations like the bleat of a lamb behind your picnic windbreak. The effect is disconcerting, but all the more brilliant for it.

‘The Path between the Mountains of the Moon’ shows McMillan’s skilful balance of humour, emotion and landscape at its best. It lets us in to ‘a local idiom’ with a chuckle in the first line: ‘The joke is…’, sweeps us up in the atmosphere of the landscape in the second stanza:

And buzzards riding thermals

above needle crags. When we pass

and by the last lines, treats us to a moving snapshot of his relationship with his daughter:

surging just ahead of me,

until she’s lost in cloud.

The flock are the quiet observers in The Conversation of Sheep, watching the comings and goings of homo-sapiens in all their ridiculousness, tenderness, grief and joy. Needless to say, the sheep are somewhat sceptical, and we learn a thing or two about our own species through their eyes.

Ellie Julings

Beautiful review, Ellie! I love your description of ‘real’ photographs!