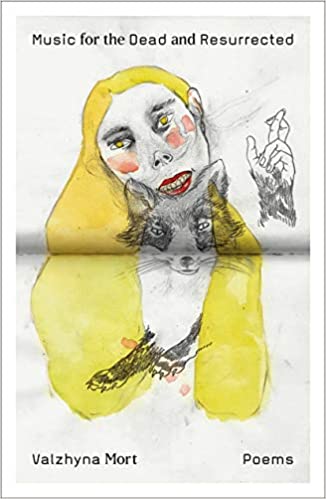

Music for the Dead and Resurrected

Valzyhna Mort

(Farrar, Straus & Giroux 2020); hbk: £19.95

Valzyna Mort’s third collection Music for the Dead and Resurrected was published in November 2020 amidst ongoing protests in her native Belarus regarding the fraudulent election of Alexander Lukashenko in August of that year. The majority of these poems take place in and around Minsk, the ‘city of iron and irony’ where Mort was born. Born Valzyhna Martynava, her pen name ‘Mort’ befits a collection dedicated to the dead. In an interview with NPR, Mort describes the deaths of her family as an ‘archive of silence’, a silence representative of the failings of ‘official’ country narratives in omitting civilian tragedies. Lines like ‘As the whips of silence rises, language tucks in its tail’ indicate the submission forced by the lack of representation and its necessity, as well as showcasing Mort’s prophetic tonality.

In one poem ‘Self-Portrait with Madonna on Pravda Avenue’, Mort writes about seeing Raphael’s Madonna inside of a classroom:

Her docile features didn’t seem beautiful.

Like hush money,

she was handing the child a breast.

The reference to hush money alludes to corruption, a common feature in societies of political tumult. Throughout the collection, an atmosphere of distrust acts as a bass note, keeping the lyrical melodies of her images in line. This distrust presents itself often as a linguistic unease — the search for the right words as a simultaneous search for a sense of self — significant as the poet also writes in Belarusian, a language considered vulnerable by the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger.

The struggle for language can also be understood by the poignant use of trees in this collection. For all the ghosts of the dead, who have been omitted from the history books, these trees stand as the last living witnesses of the tyrannies. Their testimonies have the ability to return language to the poet, like in ‘Psalm 18’:

I pray to the trees and language migrates down my legs like mute cattle.

I pray to the wooden meat that never left its roots.

Also a witness, the poet’s grandmother features prominently in this collection, the survivor of the family. In ‘Bus Stops: Ars Poetica’ she describes her grandmother’s purse:

In the purse that held —

through seven wars —

the birth certificates

of the dead, my grandmother

hid – from me –

chocolates.

The repeating image of the purse’s ‘screaming mouth’ fashions this object into a symbol of both grief and maternal love, and one senses that the grief is echoing, is practical, is a purse full of birth certificates and chocolates. It is a startling elegy.

A glimpse into the poet’s childhood in Minsk is discernible throughout the collection also. When writing about her schooldays, Mort reiterates the chlorine-scent of the school ‘chlorine, opium of the pupils, granted us purity, absolution of sins.’ The potent description of chemicals alludes to the Chernobyl disaster, of which Belarus received 70% of the atmospheric fallout. Radiation lingers in these pages, ‘an etymology of soil’ as she describes in the poem ‘Nocturne for a Moving Train’. It is a repeated motif, alongside apples, accordions, tower blocks and identities. These function much like musical notes, arranged in the melodies that comprises these pages.

Mort’s attempt to break the silence of her family and country with her music, which pays homage to her heritage whilst also asking important questions regarding this very heritage’s consequences on her conception of self – a self born from generations of displacements and disappearances. These questions are perhaps best canvassed in the long-form poem ‘An Attempt at Genealogy’.

And indeed, ‘disappearance’ is still is an issue for Belarusians regarding their ongoing protests – an conflict which finds resonance in lines such as ‘Little Songs’:

Our famous skills

in tank production

have been redirected

at students and journalists.

These are remarkable poems in a dense and beautiful collection. This is poetry of descendants asking questions about the legacy they have inherited and attempting to find answers in verse. This is poetry confronting tyranny.

Cheryl McGregor

Leave a Reply