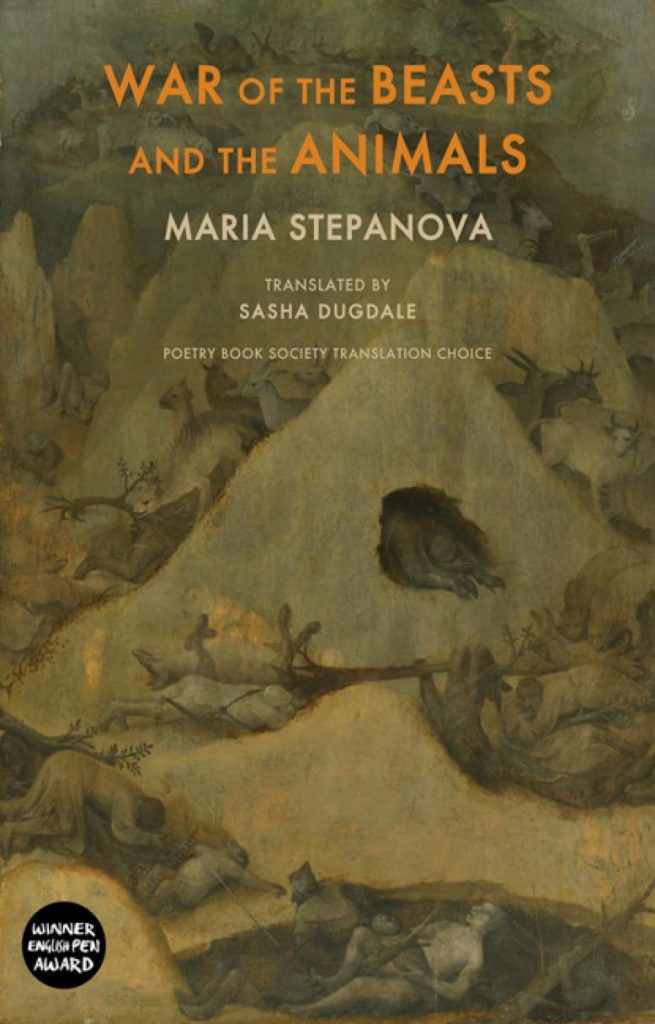

War of the Beasts and the Animals

Maria Stepanova (translation by Sasha Dugdale)

(Bloodaxe, 2021); pbk £12

The forthcoming War of the Beasts and the Animals is Maria Stepanova’s first collection to be translated into English, and the second of three of her books to introduce themselves to the English-speaking world this year. In her native Russia however, she has won several prestigious awards for her poetry, essays and journalism.

The translator’s forward, in which Sasha Dugdale explains the challenge of translating something so culturally and linguistically specific, is in itself a fascinating read for anyone interested in the art of poetic translation. She describes their work together as ‘a triangulation rather than a translation. It is the result of a dance between the original poem, Maria and I’.

The collection opens with two long poems; ‘Spolia’ and ‘War of the Beasts and the Animals’. Similar in form, they are both chaotic and deeply layered. In both poems, Stepanova sifts through language, culture and identity in an attempt to make sense of them all. She reaches no conclusions, but something fascinating is revealed in the attempt. In her poetry, Russia is a country torn apart and remade line by line, a patchwork of truth, myth and dogma stitched together with shreds of memory.

‘Spolia’ is an onslaught of images and references, each line appearing momentarily as if lit by a camera flash. The effect is an illumination of the whole far more nuanced and evocative than ordinary daylight could reveal. Dugdale describes for the English reader how dense these poems are with reference and quotes. I no doubt missed most of them but the poems with their varied rhythms and scenes nonetheless maintain a sense of archive – a history unfolding from amongst its own records.

words are attached to things

with old twine

and people lay down with their tubers

in the ground for all time[.]

‘War of the beasts and the animals’ is ‘Spolia’s’ more violent and visceral counterpart, diving deeper into the heart and earth of the matter:

life, you are a gash in need of stitching

death, you are a crust that yearns for filling[.]

The juxtaposition of imagery is stark in this poem, an effect that casts a vivid light on each subject, whether in light or shadow:

the sightlessness of moss on boughs

anxious flight

armoured vehicles

lenses

aimed at movement[.]

The middle section of the book gathers together earlier poems including the surreal ‘Fish’, a poem that plays within the claustrophobic shadows of wilderness exploration and the myths that make it out of the ice. Equipment is sabotaged, helicopters circle and a monster appears:

And there, to the soothing hiss of the radio

The fish and the mechanic are playing snap.

War of the Beasts and the Animals closes with another long poem interrogating the role of poetry in the face of war. Commissioned for the centenary of WW1, ‘The Body Returns’ is certainly embodied; by human, landscape, even poetry itself is given form: ‘Poetry, speaking Danish, lying under the earth, female’. Its voice is sometimes strangled, sometimes screaming, sometimes wry at the atrocities of conflict:

And poetry speaks and knows what it says: I said

You are gods, I said, and all of you are children of the most High

But you shall die like fools[.]

Ellie Julings

War of the Beasts and the Animals is published by Bloodaxe on 25 March. In Memory of Memory is out now from Fitzcarraldo Editions. The Voice Over, a collection of essays and poetry is released by Colombia University Press on 23 March. Maria Stepanova appears at StAnza’s Poetry Centre Stage on Saturday 13 March at 4pm.

Leave a Reply