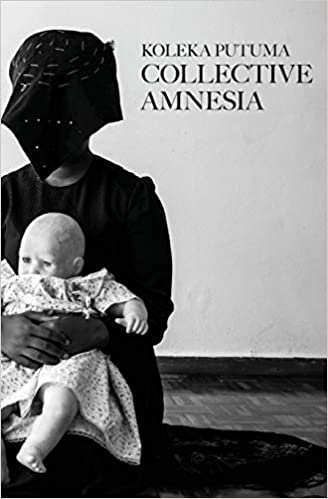

Collective Amnesia

Koleka Putuma

(uHlanga, 2017); pbk £14.00

In her poem ‘hand-me-downs’, placed boldly near the very beginning of her debut collection Collective Amnesia, South African poet Koleka Putuma writes: ‘I have learnt how to say my glass is half full even when it’s broken’. This collection as a cohesive entity offers no such pretence or platitude. Beautiful, thought-provoking, and scorching in its honesty, Collective Amnesia is a cathartic pouring-forth of words left unsaid for far too long.

Putuma’s poetry is heavily intertwined with her own identity. Here, she explores what it means to be a womxn (her own insistent terminology) in a world where men feel entitled to your space and your body; what it means to be a lesbian under the eyes of Christianity, or under the hands of a lover; what it means to be a Black South African living in a country that white people laid unjust colonial claim to.

You can’t go up the mountain without going past my property,

She says.

I ask if she owns the mountain

And she says she owns this land.

(‘mountain’)

Much of the third act of the collection, ‘Postmemory’ (following ‘Inherited Memory’ and ‘Buried Memory’), picks apart the hypocrisy of colonizers and their descendants claiming they can own anything on stolen land. ‘mountain’ in particular focuses on how unthinkable it should be for someone to take a mountain in a country they essentially invaded and claim it as private property – and yet it happens, with mountains, with people, with ways of life. The repetition in this poem, over and over again, describing how colonialism and its knock-on effects wear one down little by little, is exquisite. It gives the impression that while this collection is powerful on paper, it could be transcendent if performed aloud.

Her prose carries something of Audre Lorde in it – both ephemerally and quite literally. Putuma goes as far as to name her as part of her ‘lifeline’ in what is presented as the poem-that-is-not-a-poem of the same name.

Several of the poems in Collective Amnesia tell stories that so enrapture you to the point where you find yourself carried across several pages before you remember to blink. Others take the opposite approach, though both have equal power. In poems such as ‘suicide’ and ‘apartheid’, Putuma affixes a footnote to the title, no more than a heavy sentence or so in content, and leaves the reader there in the liminal white space between introduction and resolution. The collection even begins with one such poem, entitled ‘storytelling’, so that each subsequent invocation of the form brings to mind that same clarity and anticipation experienced when opening the book for the first time, that first look with fresh eyes. Memory. A micro-history between the pages.

The collection contains two centrepieces at opposite ends of a very storied table – ‘water’ and ‘no Easter Sunday for queers’ are far and away the standouts in a collection that makes for very tough competition.

“Our Father” is a mantra/a bridle/a stutter on the playground with mean

kids/a prayer malfunctioning in my lesbian mouth/our Father/my

father is a stranger on the pulpit.

(‘no Easter Sunday for queers’)

You have taken a liberty to colonise the concept of God,

gave God a gender, a skin colour,

and a name in a language we had to twist our mouths around.

(‘water’)

Both explore what it is like to be constantly exposed to Christianity through a straight, white lens when one is neither. The former does so in a particularly fascinating way, flowing from contrasting bullet-pointed lists to free verse segments to stanzas of overlapping stream of consciousness and back again. Form and content mix together here in a way that allows each to strengthen the other.

Black girl –

Live!

Live!

Live!

(‘lifeline’)

At its crux, Putuma’s work embodies life. Memories, as she presents, are proof that someone has lived, is alive, will continue to live on even in death.

Simon Jordan

Leave a Reply