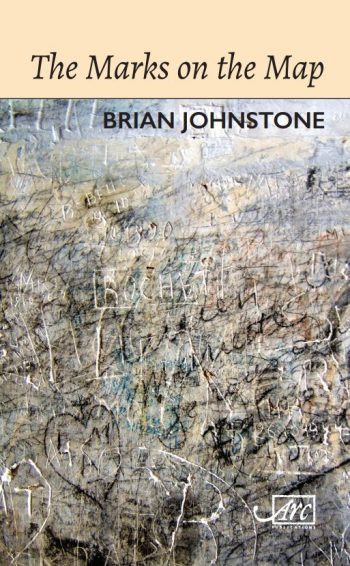

The Marks on the Map

Brian Johnstone,

(Arc Publications, 2021); pbk: £10.99

Brian Johnstone is far too well-known a figure in the Scottish poetry scene to require any potted biography here. That said, which Brian Johnstone will you meet in The Marks on the Map, his most recent collection?

Ask the avowed Hellenophile Brian Johnstone about nostalgia, and he will answer carefully. Tracing the etymology of that now-depleted word, he will alert you to its much more powerful and encompassing origins. The Homeric νόστος (nóstos), meaning ‘homecoming’, compounded with ἄλγος (álgos), giving ‘pain’ or ‘ache’ and this 17th century Swiss medical student’s coinage offers a great deal more than the English word’s current saccharine nature. That very ache in exploring the elsewheres of both a personal and a collective past is at the heart of his poetry.

Then, there’s the storyteller Johnstone who unravels narratives found on gable ends and pounded into paths hardly dotted on maps. Indeed the poet has long connections with cartography dating back to his earlier reflections on Terra Incognita (2009).

Sometimes Johntone’s poems develop from evidence on photographic plates. That makes sense; he is also a keen photographer:

[…]to dramatize the things we’d have forgotten

but for an eye like his

that framed this group of dwellings

harried by the sand Minch winds were drifting in [.] (‘Adam on Mingulay.’)

So very Johnstone (as well as so very Robert Adam), that timely finding of the theatre and recognising the importance in what so had so nearly peeled away. His is the deep examination, comprehension and cherishing of heritage before it’s lost forever. That’s equally true whether he is studying an ancient road or considering a fleeting, but key moment in the life of a Greek family at the kafeterion.

Many of the opening poems describe an architectural place of entry or exchange: ‘I can open your door, if I think myself back’ (‘Heritance’), ‘The windows are open to air the flat’ (‘A Back Street in Leith, 1911’), as indeed the reader crosses certain thresholds and is walked through tightly contained tercets or couplets into another time, and often into another place. Here, we have the poet as an archaeologist. If the photographer in the poet shines through in his attentiveness to a scene’s composition, and his ability to isolate the almost overlooked intrigue amongst the commonplace, then his jazz musicianship will be heard in the pacing, pausing and pronounced rhythm of his lines. It is well worth hearing Johnstone read to appreciate that quality in its fullness.

Taped off, out of bounds,

the curious kept at bay[.](‘Wreck to Ruin.’)

Already, we have so many Johnstones. There’s the historian poet, meeting fellow creatives Louis Armstrong, Gainsborough, John Clare and more. Sometimes he meets a boyhood self too, as here in ‘British Bulldogs’:

It’s these you must encounter, run towards

as if there wasn’t a tomorrow, only yesterdays

they believe in, you do not.

Revelations of pasts almost invariably have messages for the present and how we meet the future, of course. The generous endnotes tell us that this relating of a childhood team game ‘might also be read as an allegorical take on the Brexit referendum’. True, and perhaps it is threaded through with still more continuing parallels, which the highly politically-aware poet sees all too well.

They have the stubs, some fifty-six of these,

all punched, a blank triangle

nicked from every ticket’s edge [.](‘The Last Train from St Fort’)

Yes, indeed there’s the train enthusiast Johnston, framing images with his photographer’s eye. Consider that insistent opening line, presenting those hard-hitting visual facts, then moving to the steadily more tiny detail, with its echoing metaphor, to record the Tay Bridge Disaster in a way that a notorious predecessor poet never could.

The Marks on the Map offers so many journeys, and so many Brian Johnstones. We are fortunate in being able to travel them all in this collection without narrowing our choices.

Beth McDonough

Leave a Reply