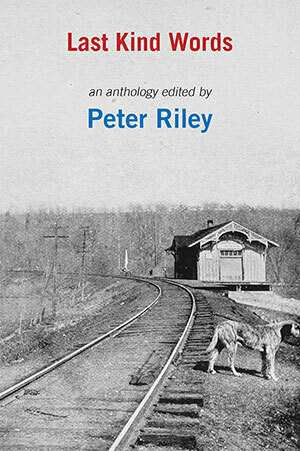

Last Kind Words: An Anthology

Peter Riley ed.

(Shearsman Books, 2021); pbk: £10.95

In response to an old Blues song performed by Geeshie Wiley, Peter Riley has brought together established poets of varying styles. Notwithstanding a spelling error, a misdate and some distracting formatting, Riley and his troop have created a muddy-watered pool for the reader to lounge in.

Peter Riley’s stanzas are laid out simply, later using Tom Waitsian imagery and establishing both the call and response format, and the theme of communicating with the dead. This theme is central to the performance of the anthology, with key examples being the works of Ian Duhig, Judith Willson, Tony Baker and Laura Potts. Each of these poets tackles the format with individuality, though their contributions are sown together by a sense of communality.

sketches in black ink with no

substance, no names, what are they?(Riley, untitled)

Rhythm, rhyme and repetition are key to the traditional song structure of the Blues. This is mimicked well by Kelvin Corcoran and assisted further through his alliteration and assonance, which adds weight to socially-concerned metaphors. Additionally, these techniques are pushed further by Zoë Skoulding, whose subtle interpretation and scattered punctuation play with the interpretation of sound, of how it is both heard and unheard.

it was an owl for wisdom, but I can’t remember

the sound of the words, only how I understood them(‘Anecdote for the Birds’)

Interpretation of history links with the ever-present theme, played out through intertextuality within several of the poets’ works. Michael Haslam responds to the prompt with essayistic prose, calling to mind the way in which the Blues acts as a cultural touchstone, and uses historical events as a catalyst for this exploration.

This is linked to John Seed’s structural dissection and rearranging of Geeshie Wiley’s ‘call’. Within this poem, Seed makes reference to poet Hart Crane and the never-built masterpiece of Tatlin’s Tower. These notions of artists being disassembled by the concepts they wished to communicate with are assisted by the aforementioned structure, contributing to the communal ‘response’.

Communality is retold in new form through Tom Lowenstein’s intriguing interpretation of intergenerational preservation of art and history, complemented through the poet’s short, impactful stanza structure and syntactical complexity.

The concept of syntactical interplay is performed effectively in Jon Thompson’s poem, which conveys the rumination of an isolated person. The poet’s use of syntactical thought-loops is particularly effective – the ultimate lines of stanzas having interrelating re-readability. Although this could be regarded as stagnating on topics, I think through lingering on such lines we, as readers, are able to contribute to the communal aspect of the anthology.

An inward loneliness moves over the field.

The stillness that accompanies a prisoner’s last meal.(‘Names Made for us in Another Century’)

The most noticeable poem risks being interpreted as nonsensical. However, I think that Khaled Hakim’s jargon-heavy and syntax-subverting exploration of often brutal imagery is effective precisely because it is challenging. Additionally, through its aggressive formatting, a line can be drawn between Hakim and the hoarse cries of Howlin’ Wolf.

ONTIL I CANNOT SPEEK O LORD

until the pips has sqweekt

singing O WO WOAH WO, OH WO WO(‘The Ballad of Geechie and LV’)

This echoing of previous Blues figures, their legacies and through that a communication with the dead is lulled to sleep by Peter Hughes’ closing poem. This poem’s beautiful use of lyrical wordplay and assonance melds together a continuous stanza of imagery akin to Blind Willie Johnson’s classic instrumental song – I won’t spoil it for you!

Riley’s troop successfully plays with the Blues’ tenet of community, banding together to both strengthen and build upon one another’s writings and the original words of Wiley. Go lounge a while with these writers, bring yourself into the conversation and enjoy that muddy-watered pool.

Nathan Fordyce-Wright

Leave a Reply