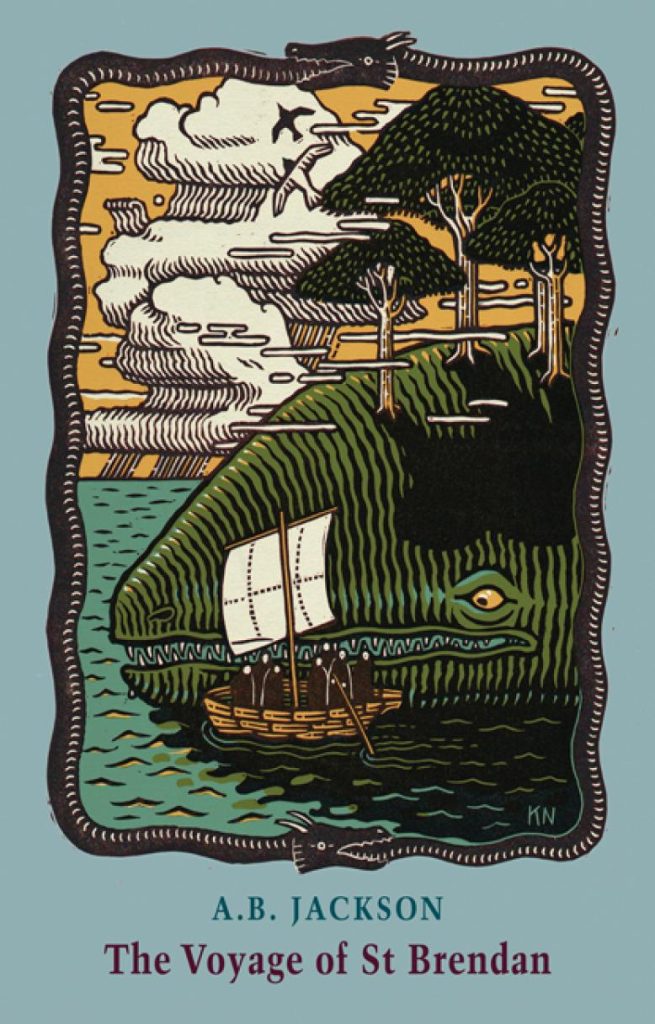

The Voyage of St Brendan

A.B.Jackson

(Bloodaxe, 2021); pbk: £10.99

The book you burned, that marvel-busy book

is fact not fiction. Abbot, hear my curse:

you’ll sail abroad, prove wonderstuff on earth.

(‘The Boat’)

If ever a book wears its scholarly research as a jolly cloak, then it is The Voyage of St Brendan. When A.B. Jackson reaches the final page of his post-collection notes, he quotes George Mackay Brown’s play The Voyage of St Brandon: ‘Imagine, say, a couple of country children on a roadside on a spring day. Tell the story of the voyage as if it was for their ears only.’ Jackson finishes his book, responding to that urging with ‘ It is advice I have kept in mind for my own version’.

How many variants of the St Brendan legend survive from early Irish immrama, through the 9th C Latin Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis,through Anglo-Norman texts, Middle Dutch and High German, and indeed far more? Though the poet has studied them all, this interpretation is drawn principally from the 14th C Middle Dutch. The roots of his quest into the legend are detailed after the poems, and make for an engaging read in themselves. Yet if I am making this sound a slightly worthy chore then I am failing this glorious book. The fully epic poem of ancient legend meets Michael Palin’s Ripping Yarns. A veritable romp of ‘an odyssey defined by sublime fictions’. Fabulous.

Those with a fondness for Anglo-Saxon ways will pick up on allitero-stressed patterns, kennings and compounds. Jackson delivers the narrative in both rhyming stanzaic forms and prose poems. Wisely, he reins in the former enough to avoid an overdose of the perhaps expected heroic couplets, which at book length become ‘too much hammer, not enough harp’. In his endnotes he details his reasons for using the prose poems as he does, but I’d recommend reading explanations afterwards, and finding intuitively why his shaping works. You will notice enjoyable changes in structures as our heroes move from dry land to that ‘coagulated sea’.

Certainly, it would do no harm to compare Coleridge’s much more miserable Ancient Mariner’s becalming with the genial and holy Brendan’s voyage on his Cog (a currach or coracle). Ancient he may be but Jackson’s references cross the centuries with

Dead-eye loan sharks

crap-wigged kleptocratic bampots

with shilling hearts.

(‘Hellmouth’)

I wondered briefly if some of the references might be too contemporary. How will a sly dig at Tik-Tok stand up in the longer term, for example? This, after all, is a venerable tale. But I was missing the point. St Brendan’s legend has had so many incarnations, well-documented here by the poet, and Jackson is the current storyteller telling it for our times. How someone recounts the voyage for those who may or may not be around in centuries to come is hardly Jackson’s concern. He carries the grail for now. The poet’s decision to write in the present tense makes perfect sense.

We need to enjoy how ‘Brendan’s mind was fruit bats in a tent’ (‘Thirsting Souls’). If you are not convinced yet, consider:

His pet fly, Quilty, was in truth many flies called Quilty over countless generations of one original fly, or some said, any fly whatsoever that flitted through Brendan’s day, due to the cracked milk pail of memory and the lack of distinguishing features in houseflies. In this way, also, he avoided such grief as follows the loss of a precious companion.

(‘Brendan’)

Yes, The Voyage of St Brendan has an opulence of images, tales and language, and it’s a book to share at a fireside. For me, in this time of darkness, it was something more too. Rightly, currently we are somewhat swamped by calls for poems of pestilence and environmental catastrophe. Poets need to address our dire times. But in the travels of this couthy, quirky saint, agog at the world’s marvels, brimming with forgiveness and compassion, I read of a planet worth saving. I read hope.

Beth McDonough

Leave a Reply