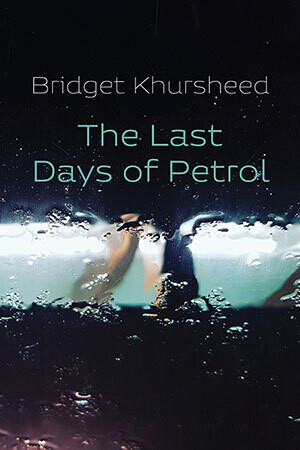

The Last Days of Petrol

Bridget Khursheed

(Shearsman Books, 2022); pbk: £10.95

When a collection’s first line is ‘How did we get here?’, and that poem is called ‘When everything is water’, it’s perhaps hard for readers of a certain age not to hear an echo of Talking Heads and wonder at what is going wrong. In this time of accelerated ecological crisis the collection’s ominous title points that way too. The cover (with the poet’s beautiful photograph ‘Selkirk swimming pool in the rain’) describes how ‘we cannot imagine that the life we know is about to change in personal, political or global terms.’ Once in a Lifetime it is.

Don’t you want to see

the tidefast end of it all;[…]

This is your migration.

(‘Bridges seduced by burns’)

Scottish Book Trust New Writers Award winner Bridget Khursheed lives in the Scottish Borders, which seems fitting. Certainly many of these poems root in that area’s very soil, but in a sense there is also a border-challenging aspect throughout The Last Days of Petrol, though not in any nationalistic sense. What are divisions? How are they bleeding and breaking down, both for good yet as is more often here in ways which should concern us? Khursheed references the environmental catastrophe already faced by a poet: ‘look at John Clare one day finding signs and fences//and walls (‘After new year’). The disaster of the Enclosures Acts and Clare’s need to respond makes a sharp parallel with the contemporary; the detonation of that poem’s final line stuns.

Khursheed’s landscape is increasingly a waterscape, but the shapes of land, sea and air interplay too with what makes the body. In ways which are neither exactly anthropomorphic, nor pantheistic, she blurs categorisations. Her quest into how we face the coming confusion becomes all the more potent as she removes barriers in poems already fairly congested with both images and questions, and often backtracked with a military or policed presence. There’s a nod to Atwood. Even the barriers of punctuation are minimised, though not eliminated. Very few of these poems are enclosed by a final full stop.

So many dichotomies. The poet announces her ‘interest in ecopoetry’ and there is a density of very direct natural enquiry, and research as a self-labelled ‘geek’. Indeed in her rigour and her self-aware realism, it’s perhaps possible to read a certain challenge to some of the cod science claims currently rioting online. Barriers may be dismantled, but expectations of close scrutiny are not. We have come to expect our environmentalist poets to hike and camp through the countryside, which Khursheed does, but here there are also so many more poems of driving, of worlds watched through windscreens. Very frequently the view is chopped by wipers as the unrelenting rain ‘purls’. Islands may be of the road traffic variety, and lochans are newly-arrived in fields as ‘[t]he house becomes tributary[.]’ (‘The river in spate’). Air is often solid with life, human bodies may be maps and overwhelmingly, dry land is usually a contradiction in terms.

From the outset, the poet responds to Hugh MacDiarmid’s thoughts on ‘a frenzied and chaotic age’, suggesting that ‘in that journey we can glimpse the possibility of transformation.’ I struggled rather with some of the pile-ups of words and images (and doubtless that was the poet’s intention as she created the needed essence of chaos), but I navigated better through her frozen scenes where ice sharpened, chilled and cut the imagery. The transformative hopes are glimpses, but where they occur, they are beautiful. For me, they tended to coincide with the close and humane, as in the unexpectedly revelatory last stanza in ‘Standing on top of the National Museum of Scotland’, and the gentle wit of ‘Study of woods’. It’s probably sign of these times that in seeking that transformation I wanted rather more channelled hope and slightly less driving rain.

That said, Khursheed’s poems deserve revisiting and careful driving. The journey is far from over.

Beth McDonough

Leave a Reply