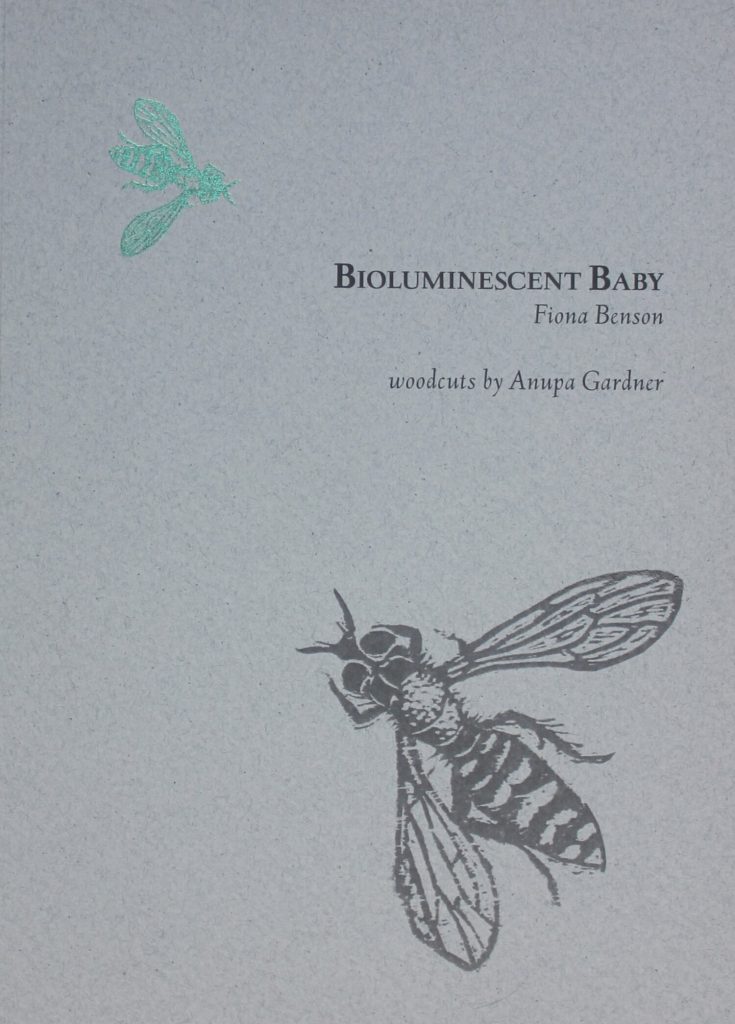

Bioluminescent Baby

Fiona Benson, (with woodcuts by Anupa Gardner)

(Guillemot Press, 2021), pbk, £10.00

The poems in Fiona Benson’s Bioluminescent Baby detail the short, intense lives of insects. They were originally commissioned by University of Exeter’s ‘Project Urgency’ as a commentary on the looming biodiversity disaster, yet these various crawly creatures compel us even further through Benson’s careful and evocative words.

After opening with a love poem to the common glow-worm (‘Love Poem, Lampyridae’), Benson moves swiftly to the gut-punch of social inequity in ‘Mosquitoes, Mozambique’, a three-page narrative that explores the mechanisms of the mosquito bite:

they use two serrated needles

to cut through your tissues, two needles to hold the flesh apart,

one to insert a chemical spit to keep your blood running,

and a proboscis to home in, to suck […]

whilst also naming those who fear them, strain to keep safe from them, researchers searching to neutralise them, and the children who succumb to them:

the malaria swells and burns till her girl arches

from her pallet bed and drums her heels, her eyes

rolled back in her head, raised beyond and gone

though her mother tries to call her home. Daughter.

Baby Girl. […]

Benson moves between the dispassionately clinical and the empathetically human without ever letting go of either, taking us with her to land on the juxtaposition at the end, the lifesaving inoculation reserved only for those on her ‘privileged Northern isle’.

The thirteen poems each reference a particular insect and are often subtitled with their Latin biological name. Although the acknowledgements page is filled with the names of scientists and conservationists, Benson’s sequence of work seems underpinned as much by an unearthing of beauty as an acute interest in the specificity of arthropod research. This capacity to turn unexpected subject matter into raw emotion is surely Benson’s gift. ‘Blue Ghost Firefly’ evokes such awe; speaking to a female dragonfly larviform, described anatomically as it takes a protective form around its eggs, but comparing it to the universality of motherhood’s sacrifices:

I too keep guard –

my daughtersthe softest part of me –

and will die

at my post

Each poem is bedded in the intricacies of life within the natural world – hidden details of mating and reproduction, feeding and survival – magnified so that we might see ourselves in their reflection.

Benson varies form throughout, with ‘Magicicadas’ and ‘Notes Towards An Understanding of Butterfly Wings’ are written as numbered instalments, others are in couplets, and ‘Wax Moths’ arranges whitespace on the page to form shaped stanzas. Danger lurks in the scant lines of ‘Wasp Theology’ while the abundant and urgent flow of words in ‘Blue Morpho, Crypsis’ reminds us of what we do to them:

Oil from my fingers rolls in tiny beads across their film,

The stains proliferate and breed: all my dirty human effluents.

The variety showcases Benson’s intellect; each subject is individually invited. Thematic precision pulls everything together: the anthropomorphising of that which we consider the most minute, insignificant and often grotesque of our natural world. The culmination of this is arguably ‘Mama Cockroach, I Love You’, which is a nothing short of a triumph of feminine empathy towards a life lived under suspicion and judgement. Benson revels in repulsive corporeality,

Or carry them as yolks

and give live birth, then feed your pale brood

secretions from your anus, or your armpit glands,

like milk; […]

whilst celebrating Mama Cockroach’s promiscuity, her grotesquely bodily birthing, joy and sacrifice in motherhood:

…Because strokingly

you caress your off-springs’ backs, and gentle them

with pretty pheromones and chirps. Because

you purr when your young stroke your face.

Forever alluding to the larger issues of climate, and the meaning and fragility of our own existence, Benson also keeps us in check, reminding of the inevitability of all our basal natures yet compelling us to find joy in the way we ascribe meaning to our instincts, framing them as choice, as love, as endeavour.

Hannah Whaley

Leave a Reply