The Hamster & the Cat: An Interview with Rachel Plummer

After two years of pandemic induced online communications, you would think I’d acclimatised to the online call by now. Yet I still find myself startled by the suddenness that is the beginning of a Zoom call. You’re alone in your room staring at yourself on the screen, checking the time, your appearance, what’s out the window?, the time, your notes, the time… Then zap, there they are, a person has manifested on your screen. In this instance, it’s poet and creative writing teacher Rachel Plummer who smiles at me across the miles from their home in Edinburgh.

Thick pixels and a musty connection distort the objects that surround Plummer who sits on a teal sofa fit for nap heaven. Wearing a knitted jumper the colour of winter clouds, their hands are busy knitting together a much smaller garment. An item of clothing so small but with the power to spark our conversation, Plummer tells me it will become a pair of trousers for a little girl, and it will eventually be adorned with fairies too. Plummer knits away, only to stop when pondering my questions. Their hands drop out of the frame as their mind starts knitting a well-thought-out answer for me.

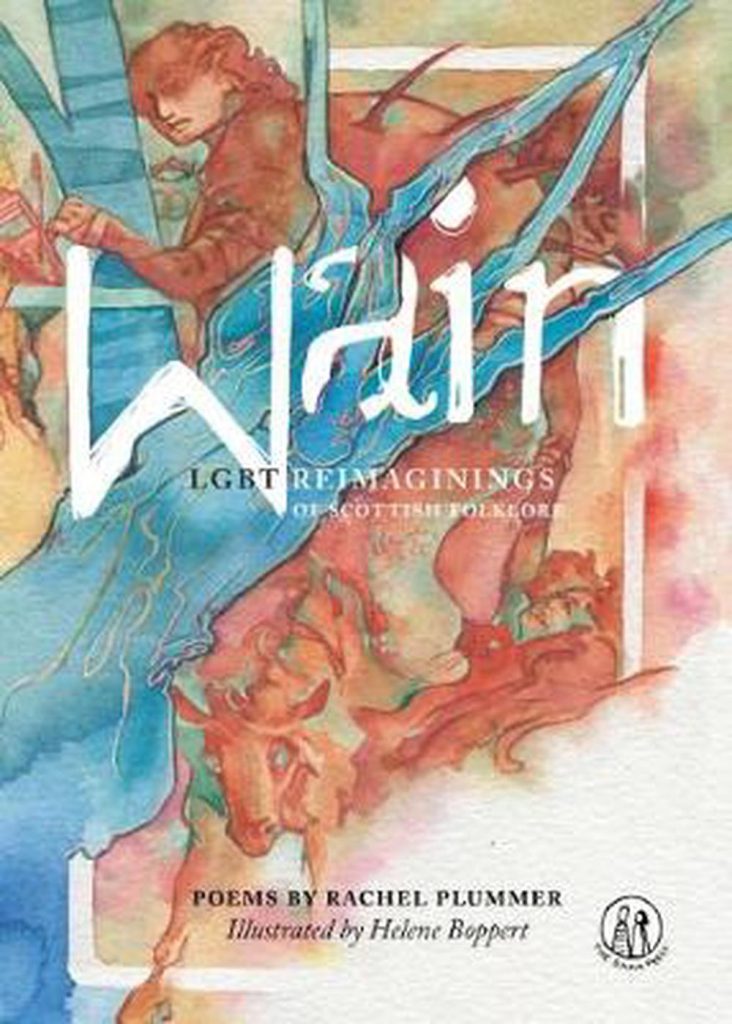

Published in 2019 by The Emma Press, Wain is a reimagining of Scottish folklore with an LGBT focus. After receiving the 2016 Scottish Book Trust New Writers Award, Plummer was commissioned by LGBT Youth Scotland to write what would become Wain. They describe the experience as fantastic and recall discussions they had with some of the staff there: ‘as LGBT people reading folklore and fairytales when we were younger we often identified more with the monster or the villain or this idea of considering ourselves to be in some way monstrous because of how society portrays us’.

Plummer’s research process while creating the collection included visiting a storytelling centre as well as reading up on folklore books and old Scottish nursery rhymes where they examined the stories from different places. Plummer calls themselves a keen student of Scottish folklore, ‘I’m still not in any way an expert,’ they confess, ‘there’s still so much. I would have to study for a really long time to be anything like an expert’. At this point, Plummer’s son twirls into the room. He soon becomes the star of the show, a little whirlwind of joy, hopping about on the back of the sofa behind Plummer. He reminds me of a question I wanted to ask but had forgotten to write down regarding children’s toys and literature. I enquire about Plummer’s thoughts on how heteronormative these things still are today. In response, Plummer sighs in agreement and comments, ‘It’s shocking how regressive children’s literature is particularly. And I’m not even talking about historic children’s literature but the stuff that’s being put out today, it’s so old-fashioned, even in terms of-‘ Plummer pauses to answer a fake phone call that has been presented to them by a small hand. At this point Plummer escapes across the room, retreating into a corner.

Now framed by a curtain patterned with wildlife and a clay jug engraved with a design the pixels won’t allow me to see, Plummer continues their answer,

What I wanted to see more of was queer people just existing within the universe of the story. Villains, side characters, main characters whose story isn’t necessarily about being queer; it’s just part of their identity.

Another inspiration for Plummer which fueled their writing of the collection was a survey by LGBT Scotland which they stumbled upon during their research. Plummer describes being particularly inspired by the comments left by young people who wanted more representation, not necessarily just to see themselves in literature but for straight cisgender people to see that they exist in literature as well. Plummer continues,

I don’t use the word “lesbian” or “trans” or “asexual” anywhere in the book because I think even from quite a young age we come at those words with quite a lot of baggage and preconceived ideas of what they mean. I wanted to write this with none of those words. I wanted people to put their own experiences onto that and relate to it in different ways so that somebody who maybe wasn’t LGBT, maybe a cis person, could read a poem about a trans character but still felt they could identify with them and take that through to empathy.

The beauty of this book extends further than the words. It explodes in colour through the illustrations by Helene Boppert. Her work truly makes this collection stand out, the watercolour designs of the fairytale creatures emphasise the beauty of the poetry and set one’s imagination alight. Plummer comments on their journey to find the perfect illustrator for the collection: ‘I was really keen to work with an LGBT illustrator or someone who had some stake in our community rather than just the in-house illustrators The Emma Press usually use. The Emma Press were really great too, they put out an open call for illustrators where people had to submit a portfolio and a little statement about themselves and their work’. Out of hundreds of submissions a long list was created from which Helene Boppert was chosen.

Plummer talks of sewing the collection together like a patchwork blanket. They begin by laying out the poems and deciding which will fit well together both visually and thematically on the page, which poems will bookend the collection, and which will land on the third page – as they have heard that’s where readers look when they first pick up a book. We go on to discuss the finer details that have major impact on the writing, such as the title. Wain was the working title for the collection though it still went through a few different iterations. Originally spelt ‘wean’, it was changed due to concerns that an English audience might not understand the Scots and believe the book to be about weaning a baby. Speaking of babies, this reminds me of a wonderful quote from Plummer about writing poetry: ‘It’s a horrible metaphor so apologies,’ They said, ‘but it’s like throwing up – writing a poem – it comes to a point where it’s gonna come out of you and you can’t stop it’. I couldn’t agree more.

Possibly the opposite of the projectile poem is writer’s block. Plummer conquers this notorious condition through teaching. They teach for all ages from primary school children to adults in workshops, though it’s working with children that inspires them greatly.

I think part of it is you can get jaded with industry stuff where we maybe lose track of why we are doing it and then you get into a room with these young people who are just literally bouncing around. I’ve had kids climb up on the table because they’re so excited by an idea they’ve had. That’s why I do it, because I want to feel that feeling and I want to create something. Not because I want to win some award or be patted on the back by some big wig. That’s my cure for writer’s block.

The teaching world isn’t the only place where Plummer finds inspiration, the natural world is just as motivating for their writing. Plummer is writer in residence for Craiglockhart Hill in Edinburgh and spends as much time as they can there. Mushroom spotting and walks in the woods are both a passion of theirs as well as fuel for their creativity. Plummer’s love of mushrooms is deep rooted; they hold up a handmade, pocket sized mushroom dressed in a red cap with buttons growing up its stem.

Whenever I go out for a walk in the woods, by the time I come home I’ve got words. Don Paterson calls them the lines you get for free. When you come back and you’ve got a few lines or phrases ready to go and you just need to build the poem around them.

Plummer writes whenever they can, wherever they can, and that is the advice they pass on to me. They tell me there was a time when they followed the advice of having a wide open window in a quiet place to write but now they will write on the back of a receipt with CBeebies blaring in their face. Such is parenthood. In fact, being a parent is what set Plummer on the journey of writing the collection in the first place. Their daughter is also a lover of Scottish folklore, a budding young fan of the fantastical stories which contain the unsettling lure of the uncanny. Plummer remarks:

I started out doing it for her and whenever I would read stories to her I would often gender swap the characters because I wanted to reflect families like ours and people we knew that were missing from the literature she was reading…from most children’s literature actually.

Wain is not solely for a younger audience, though Plummer did have young people in mind when writing the collection. Plummer tells me they wanted there to be a cross generational appeal, especially since it’s the adults who buy the books for their children. ‘I hoped when I was writing it that certainly some of the poems would speak to people of all ages’. The first poem they wrote, long before the idea of the collection came about, was ‘Selkie’ which they tell me was not written with young people in mind at all. It was only following the commission and advice from the Scottish Book Trust that Plummer began writing for a more universal audience, one that is inclusive of the younger generation, ‘The advice they gave was basically “when you’re writing this you have to imagine where it’s going to be on the shelves in a bookshop and write into that space”’. We discuss the constraints and demands of the industry and what writing for a specific audience means.

Plummer will be giving a talk at the StAnza poetry festival on March 10th with Andrés N. Ordorica about the author-editor relationship that they share. I wanted to pick Plummer’s brain about the editing process; they describe it as ‘the best nerdy fun’. Plummer is a freelance editor, they like to pick authors whose work they enjoy and who they know and whose work they can make useful suggestions towards, ‘It really is fun to dig in huge detail to someone’s poems and nerd out over it and spend hours on the phone discussing the details’. After sharing a few editing tips such as splitting up the poetry into line edits first before moving on to the larger structural edits, I draw Plummer’s attention back to their own collection.

When pondering the subject of their favourite poem to write, Plummer rolls the question around in their mind before speaking: ‘There’s a few. I have a real fond spot for ‘Selkie’ as I wrote it first, and I suppose I wrote that before the whole idea of the book came together so that was quite fun to write without pressure and expectation’. Then Plummer mentions my favourite poem of the collection, ‘Nessie’. Their enthusiasm pours through the screen only to be met with my own bubbling excitement. Another favourite of both myself and Plummer was ‘The Seven Big Women of Jura’. They tell me these women ‘crop up in a lot of other stories but they don’t have their own story all to themselves. I wanted to give them their own poem. I imagine them as this kind of polyamorous commune of giant lesbians’. We share a laugh at this fantastical idea.

It wasn’t all smooth sailing and giant lesbians however, there were a few poems that challenged Plummer during their conception. They found themselves at the stage where they had written most of the collection but felt something was missing. This was due to Plummer’s ambition to encompass all identities within the book,

I wanted to include lots of different identities and experiences so what I found difficult was trying to write a poem about asexuality without using the term asexual. How do I convey that in a way that makes sense to people?

Eventually, they got there and felt the book represented people of all identities and was ready for publication. But how do you know when a collection is truly complete? Well, Plummer argues that it depends on the project, ‘It’s maybe more of an art than a science. A mentor of mine once told me that you know you are done when you have started working on the next thing’.

Plummer, with the kindness and curiosity of a true nature lover, asks about my own writing and offers advice for breaking into the industry. They flip their laptop around to show me a bookcase full of leaning books and sleepy poetry pamphlets. The pamphlets, full of dreams, spill out from their designated shelf and invade the shelves below. That’s the advice here: invade the industry with your work, ‘Pamphlets give a snapshot of a writer,’ Plummer says, and often it’s something that feels more raw and in progress and there’s something really interesting about that. They feel transient, experimental, and like they were of that moment’. The pamphlets are tucked into corners and in-between novels, breaking bookshelves and industries with the weight of their ambition.

I close the conversation with a final question: ‘If you could describe your writing as an animal what would it be?’ I tell Plummer that for me it would be a cat because they sleep twenty hours a day but when they go, they go, and they are bouncing off the walls full speed ahead. That is my writing. Plummer barely even needs to deliberate the question, ‘A hamster,’ they say, ‘who gathers things up and stores them for later’. At once, they have provided a brilliant answer to my question and summed up the influence of this interview perfectly. Plummer shared with me their store: seeds of wisdom and grains of inspiration which I will carry with me for years to come. And so The Hamster and The Cat share their future plans and projects with one another before waving goodbye. They hang up the call, but the voice of the other still echoes in their ears.

Renni Keay

Leave a Reply