Always do the thing: An Interview with Ella Frears

I never thought I would be in the realm of Zoom again. Staring back at myself in the fuzzy haze of a laptop screen brings a flood of memories of seemingly endless online classes over the last couple of years. I am here equipped with a pen in hand and a cup of tea at the ready, waiting for Ella Frears, a young poet and visual artist, to enter the call. I had already rehearsed what I was going to say, nerves rising to the surface of my skin. But I am ready.

Frears enters our call with apologies for being late. I, for one, had not even noticed what the time was. The nerves settle down as soon as we start chatting about the interview ahead. She is as warm and welcoming as I had hoped. There are no awkward fumbles or deadpan responses.

She calls me from her home office, she takes centre screen with her platinum blonde hair distracting from the noise of her neighbours working outside. I knew this would not be the first interview of its kind for Frears as she was also used to living online at this point – with her first collection Shine, Darling coming out during lockdown 2020.

We start at the beginning, as all good stories do. We talk about her ties to poetry and how she got to where she is now; essentially ‘why poetry?’ Frears tells me that she was not a fan of English in high school, being unable to pay attention to books or finding their length off-putting. She simply did not have the attention span to appreciate the form of storytelling – one that she has developed over time. In fact, Frears saw herself as more of a visual artist and went on to art school. Now she actually does like books, she says.

Yet, there was always something about words. The first poet that appeared on her horizon was Sylvia Plath. She was intrigued by how a poem could say so much whilst saying so little, ‘I just sort of remember being amazed about how much a poem can contain: music, action… all on one page,’ Frears tells me. At art school, her tutors picked up on her ability with words and told her, ‘I think you like words, you like writing.’ As a result, she transferred to study English and Creative Writing, and began her journey as both a visual artist and poet.

We always find ourselves back within poetry, both as a response to cultural phenomena and personal events (for example, weddings or funerals), Frears says. Although it is a niche form, it constantly surrounds us. However, Frears points out, the issue with poetry lies in the way we teach it. She says that poetry is often taught over our heads, as if we have to be part of some sort of elite clique to truly understand its meaning. To Frears, all interpretations matter, there should never be one singular response; ‘I think that…poetry cuts right to the core of that poet’s time, and a good poem can be read by anyone and understood by anyone.’

Before turning to her most recent pamphlet I Am The Mother Cat, I address her collection Shine, Darling. I personally adored it. It was her first collection and such a success. Frears gained a lot of traction as writer thanks to Shine, Darling; she was shortlisted for the T.S. Eliot Prize 2020 and the Forward Prize for Best First Collection 2020. Shine, Darling was created over ten years but formed around the trauma of her near abduction as a ten-year- old child. Shine, Darling is unapologetically loud; one of her most talked-about poems is titled ‘Fucking in Cornwall’. Frears tells me that she is constantly shocked that schools want her to come and speak with their students. Although she does want me to make note that she can tidy her material up for these types of visits, it seems rather strange.

Frears then talks about the stark difference between putting together Shine, Darling and I Am The Mother Cat. When Shine, Darling was finally published she worried about what would come next. She tells me that she wondered if people would expect her next collection to be in the same style and narrative – and whilst common themes of human nature, the self, body, and sex always crop up in her poetry, she wanted to maintain the freedom of being able to write about anything.

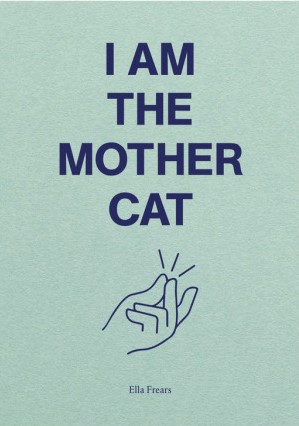

I Am The Mother Cat was written during her residency at John Hansard Gallery. It took place a year after the first lockdown, after Shine, Darling’s publication. It is all about absences and the constant need yet struggle to be creative. At first, Frears found the idea strange that she would be going from writing nothing for a year in lockdown to being in a place where she was constantly writing. However, this is why she loves residencies. Without a deadline and, she jokes, people to let down, she cannot power herself to write. Frears also admits that whilst residencies may not be for every poet, they have not only allowed her to do her best work but work as a poet full-time – an idea that sparks feelings of envy in me. She says,

it has been really sort of fruitful, as I am bad at finishing things on my own. I would write whether or not…I am asked to, but I’d never finish anything. So having deadlines allows my brain to, and I know I’m not alone in this, really clarify things. And I need that clarification, in order to make the poem its best self.

However, her biggest joy in getting to write I Am The Mother Cat is because it is so different to Shine, Darling. Part of her does not even recognise the person who wrote I Am The Mother Cat as it was written by the version of herself that had just come out of being kept in a gardenless flat for the majority of a year. It was put together in the space of six months and suddenly released. Yet, it allowed her to show that other side of her writing, enabling her to break with her past self as the version of herself in Shine, Darling; ‘I could write something totally different, and it felt sort of experimental because it was all to do with the responses to the works in this gallery’.

It is time to dive into the strange world that is I Am The Mother Cat. There are so many topics I want to touch on in this collection, especially when it comes to the focus on her lockdown experience. But I had my notes and guides in place.

The title itself intrigues me; who was the mother cat? Was it simply Frears? Or was it a collective understanding? Frears laughs when I bring it up, for the story itself was rather odd. When she was invited along to this residency, she was also asked by Southampton University – who ran the residency – to write a poem in celebration of submitting their data to REF (a research ranking of UK universities). Frears loved the weirdness of the idea so naturally agreed. Thus, she wrote the poem ‘The Submission’ that follows the story of a stressed-out academic that is becoming undone with this work. She even goes so far as to use real people’s names and paper titles. She says the mother cat emerged from the University’s Twitter feed. For some unknown reason, they kept posting cat memes, but the one that caught her attention was a gif of a mother cat putting its kitten in the bin. This brought up a whole array of questions for Frears,

I found it really interesting if you’re an unravelling academic and your supervisors were sending that meme, like what does that mean? Are they the mother cat [who] are dropping the submission in the bin? I was trying to work out who, and [if] someone in power might see themselves as the mother cat, and it started to become a thing where it was like ‘no, I am the mother cat’.

So, it was only natural that she named the collection after those experiences too. This became her attitude toward the majority of what she wrote whilst on residency. I also pick up on the theme of holes in the pamphlet; poems such as ‘Rabbit Hole’, ‘Murder Hole’, and ‘Hole Manifesto’ feel connected – not only in their exploration of holes but in the idea that you fall down the rabbit hole, trudge through the murder hole, and are left with their manifesto. Frears was intrigued by my theory but let me know that it actually came from an art piece within the gallery that was a painting of a golf course. Her initial plan for the pamphlet was to have eighteen hole poems. Yet, this backfired once Frears started writing as she quickly realised that she was not writing poems based on holes,

I started writing about nuns and other stuff…I’m not going to shoehorn a hole into a nun. And I started taking the hole poems out so only a few remain. But holes are an absence of something anyway, so the absence of the hole poems are also conceptually making sense.

When it came to the importance of absences, and specifically absences in lockdown within this collection, I ask her about her thoughts on what it was like to remain in the lockdown headspace at the residency, even though we were out of it. However, rather than focusing on the negatives of it, Frears saw it as a healthy experience. She did not write anything during lockdown; that push to be creative felt heavy. So, by allowing herself to focus on it within a space where creativity is being pushed, it was almost like confessing and finally giving in to these feelings. We see this predominately in her prose-poem ‘Bambi Hunter’ where she talks about her struggle to be creative and watching her boyfriend play Daisy – an old survival video game. By finally making something out of that time where nothing was happening, she felt her anxiety over time wasted dissolving into the background.

Talking about ‘Bambi Hunter’, Frears says it was a weird one to have out in the open. She feels slightly embarrassed about admitting to the fact she was just watching someone else play a video game rather than playing it herself. It was at this time I tell her that this is quite normal, and many online creators have made full careers from streaming their gameplay to thousands of people daily – whether on YouTube or Twitch. Frears found this idea captivating, especially since some of these creators have tens of millions of followers.

After our brief ramble about video games, I then go back into the idea of prose-poetry and its boundaries, asking what makes a prose-poem a prose-poem. Frears explains that for her it lies in the way the person perceives it. For example, there are many pieces of flash fiction she would claim to be prose-poetry even if the writer did not. She feels similar towards her own poetry. She does not mind how a reader reads into her craft, it is their own journey once it is out of her hands, ‘it was just that I am a poet, so it turned into a prose poem.’

Another theme I found cropping up into her poetry was that of hypnosis. I wonder if it was the hypnosis of the gallery itself that enables this idea to come to the surface within her poems ‘Rabbit Hole’ and ‘Light and Shade in the Manner of a Hypnotist’, and the hand symbol that decorates the front of the pamphlet that Frears later uses in the latter poem. Frears tells me that it actually came from a film within the gallery, Morgan Quaintance’s Missing Time which used archival footage to explore medical hypnosis. This caused her to go on a deep dive into the internet to find out more about hypnosis and other ways it worked.

Thereafter, this made her think more about the performance of her work. Frears says that ‘Light and Shade in the Manner of a Hypnotist’ is actually meant to be performed. It does work on the page, but the proper effect comes through the sound of it – just as hypnotism does. Yet, this was the first time she had thought about performance as poetry. Before it was simply something in the background and never really concerned her work, but now it has expanded her idea of the forms her poetry could take.

Closing our interview, I ask Frears if she has any advice for new writers, whether it be within the craft of writing itself or the industry. She draws my attention to a sticky note that she always has just above her computer screen that reads “always do the thing”. She admits that this is not the most eloquent way to say it but it gets to the heart of what she needed at the time. It does not matter what that thing may be – writing itself or something as simple as sending an email – you just need to get out and do it. Frears says, ‘always doing the thing is such a massive difference. It sounds really obvious but so often we forget.’ We leave ideas behind, thinking we will get around to them, but they often drift into the abyss if we do not focus on them in the moment.

It is for this reason I ask her about writer’s block – the horrible condition in which so many creatives face – at the start of our interview. Like many of us, Frears knows what you are meant to do but does not always do it. Instead, she finds herself falling back into comfort shows like Love Island or Too Hot To Handle whilst eating crisps, just to avoid even the idea of facing up to writer’s block. The only way Frears has ever forced herself out of it is by signing up for residencies and putting herself under deadline pressure. She admits that whilst it is not the healthiest of mechanisms, it does work – similarly to how she ended up writing I Am The Mother Cat in the first place.

The importance all comes down to the writing. It is the craft that we adore in the first place, so as long as you are making something, something else is sure to come out of it. Frears says that is what new writers need to remember. Whilst she could list off the do’s and don’t’s of dealing with publishers or magazines, it does not matter if you have not gone out to write what it is you want to write, ‘Writing stuff is the main thing and knowing the rest will come because good work will come through as it always does.’

As we say our final goodbyes, I am truly struck with everything Frears has said to me. Her smile quickly cuts back to black, and I am once again staring at my blurry face from my laptop’s low-quality camera. I wonder if in a few more years I will be in her place, not only writing as a living but living through writing. For now, all I can do is take her words to heart, make my own sticky note, and ‘always do the thing’.

Amy Turnbull

Leave a Reply