A General Practice

Anna-Louise Milne

(The Cahiers Series & Sylph Editions, 2021); pbk, £14

“Mr Bennett and Mrs Brown”, Virgina Woolf’s manifesto for a new kind of fiction, starts with a small, seemingly innocuous figure who teases her, “Come and catch me if you can”. A General Practice presents a tableau vivant of brief encounters between doctor and patient in a clinic in the forgotten back streets of an unnamed French city, “tucked away behind a row of bargain shops and fast food outfits”. In its imaginative attentiveness to place, suggestion of character, and its sensitivity to the passing of time, the world that we enter in these pages is luminous with the lives of those forgotten, ignored or made invisible.

Dr Hoda Al Asadi’s patients are often refugees or homeless — ordinary and undistinguished. Like five minute life drawing sketches where sweeping lines might capture the essence of the figure, Milne’s portraits are very economically drawn –— a scarf wound around a head, a heavy coat, a bent back, the rise and fall of breath. No back story or fully rounded characters here; instead, mood and story are suggested through objects, external appearances, and above all. bodily manifestations:

He shakes his head, still wordless, groping further round his torso, up his back, into his armpit, his forearm tensing like a brace across his chest, and then he folds, falling forward, his hands reaching for the desk, head bowed, rising and falling with each breath, as if stalled, his hair hanging like two crescent moons between his outstretched arms.

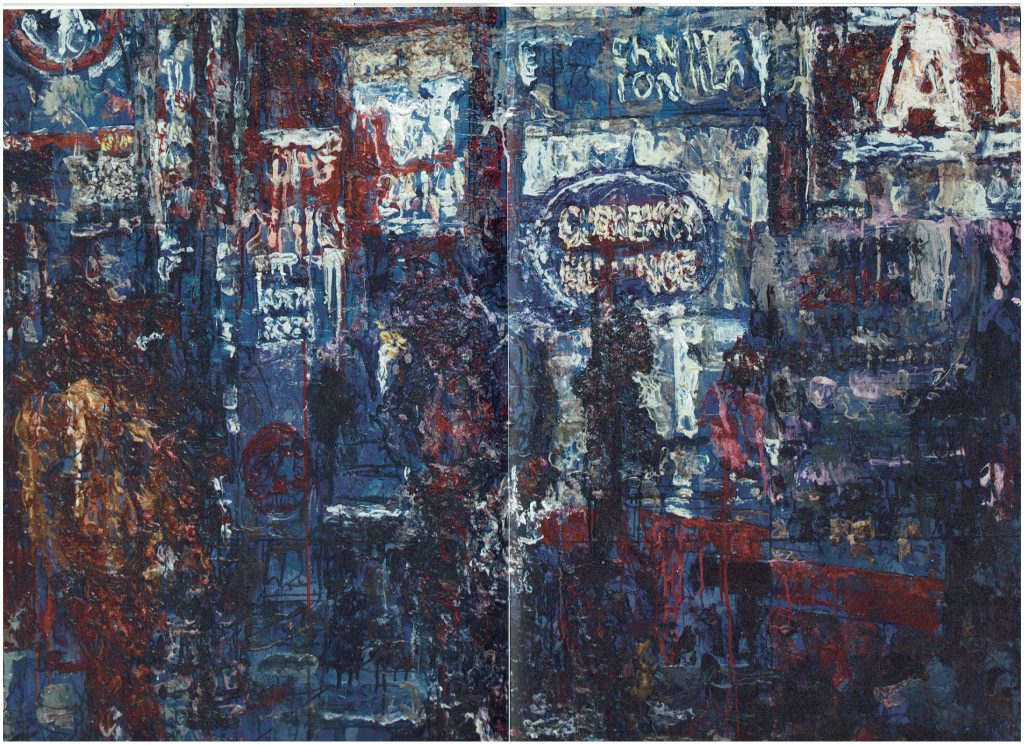

Andy Robert’s abstract paintings folded into the text hint at an occasional figure, portraits faintly discernable from thickly applied paint drips, blobs or finely drawn lines. In this way, we seem to arrive at a character, story and form from little things, scenarios where layers of words, paint, colour and textures coalesce into live people.

Perception, of course, relies on the viewer. Hoda, our proxy within the text, is a reader of corporeal signs. We are not privy to what goes on in patients’ heads and lives; written (mostly) in third person limited, we see (predominantly) what Hoda sees and hears – their complaints, grunts, shrugs and even their silences. Such eloquence demands a translation; the “swelling in the soft tissue” just above the “sternomanbrial junction” could indicate a possible “compression fracture with misalignment”. Yet if this consulting room becomes a space of translation, where non-verbal corporeal signs are transcribed into a professionalised medical language that Hoda will record in reference cards to be archived, it is also where an emotional connection, however fleeting, might be sparked between individuals.

The surgery’s practices are routinised: the physical examination, the recording of information, the washing of hands. Yet these are routinised in a manner that does suggest an anthropological fascination with rituals. Rituals are, of course, symbolic, impersonal forms that are experienced in a personal, intimate way. The consulting room becomes a sacred space of sorts. Patients make their way to a space where they are acknowledged, touched, and where healing hands might be laid upon them. Architecture is significant; doorways, waiting rooms become threshold spaces between the hushed, cloistered, safe intimacy within and the noisy boulevards full of urban life outside. Each object, routine and practice within is made luminous, and charged with meaning that seem to suggest a presence beyond themselves. Matter in all its forms is vibrant and carefully tended; the “empty shells of the chairs, stuck along the wall like open mouths, a newspaper rolled into the metal underneath, leaning in, pulling, the bins by the door, then the bucket in the cupboard.” And the women who minister this space – Hoda and her assistant, Ollie — overlooked and all but invisible to the outside world are finely attuned to its rhythms. And something of their personal relationship is sketched near the end of the text, underwritten by their domestic roles as mothers and carers.

Written in present tense, here are “moments of being” in the Woolfean sense. And such delicacy is given additional lyric charge in those long, languid sentences — perfectly punctuated – that treat writing as a musical score. In “World into Word”, Mark Doty begins his essay with the difficulty of translating life — in all its quickness and quiddity — into words… to feel “a seamless, unruptured rendering, at least for a moment, language clicking into place”. This is a fine example of that in a beautifully conceived and produced pamphlet series.

Gail Low

Leave a Reply