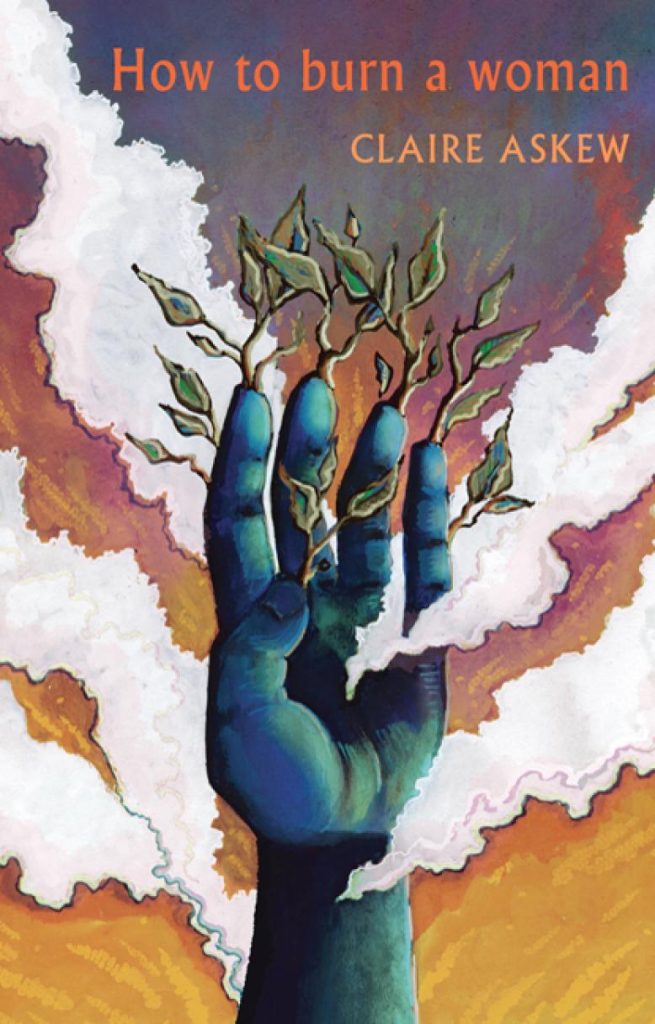

How to burn a woman

Claire Askew,

(Bloodaxe Books, 2021); pbk £10.99

In her second full-length poetry collection, Claire Askew searches for security and self-assurance within a patriarchal world where institutional power reigns over individuals. Here is fiery free verse that captures beautifully the uneven forces of female empowerment and misogyny. The resolution to this tension is addressed through deftly poetic explorations of dysfunctional relationships, exploitation of the natural world, and interpretations of Salem witch trials. By blending contemporary issues with our history, Askew exposes the claims to power, and suggests that as long as we cling to institutional influences and gendered assumptions, we will always be ‘in control of essentially nothing.’

As Askew observes in ‘Nessie to the unaccompanied minor’:

I know what it means

to be hunted: to have nets cast

in your wake, nets barbed

with all the ways they’d like to take

you apart.

Yet, ultimately, nothing can be policed completely within patriarchy and consumerism. The recurring fishing motif both symbolises women escaping male harassment, and fossil fuels and other natural resources evading extraction. Askew’s nuanced insights convey a narrator who recognises the entrapments embedded within her world but struggles to escape them. She manifests these ideas through an ironic critique of her own creative work as she states in ‘Playing it cool’,

When you get to the point

of writing poems about a man,

that’s it.

Her stark enjambment might suggest a defeatist tone, but there’s irony in the very writing on the topic that she believes taints her creative originality. The lyrical combination of natural resource extraction and male-female power dynamics expands the theme of a lack of personal and creative control:

forearms like brown rope mooring

yet another poem.

Attributing male body parts as the cause of ‘yet another’ of her creations encapsulates internalised misogyny and the lack of seriousness directed towards creative industries even as they remain enveloped by patriarchy. Initial defeatism is then set alight, and Askew’s subsequent poetry begins to blaze with rage over these injustices. Her collection is very much structured like a fire: there’s the initial cool period of finding a match and waiting for a spark to take flame – but once it begins, her poetry is set ablaze until the reader feels engulfed by its heat.

The starkness of her poetic voice lies in the self-engulfing bitterness of jealousy, hatred, and the pain of not understanding why someone stopped loving you. In ‘The women who’ve loved you,’ she writes about a woman overcoming a failed relationship, whilst the other women rejected by the same man now ‘hate her / stinking blood.’ Askew’s narrator in ‘May’ is also described as ‘a shadow thrown / to contrast my sister’s glow.’ Perfectly timed enjambment and assonance intensifies the heat in her voice, as she remarks on a sexual competitiveness that prevents female solidarity. Additionally, the poem ‘A spell for the departed’ seethes with the longing for revenge, as the narrator wishes that the life of her bedbound enemy was full of suffering: ‘I hope it was every bit this bad / and worse.’ Self-doubt and entrapment turn into consequential rage and anger; these words burn with fury that is in danger also of becoming consumed in flames.

Like all fires, there must be an end, an extinguishment, and this narrative ultimately dissolves into ashes. Her seemingly final poem ‘How to burn a woman’ states, ‘Burn me,’ and blazes with defiance:

do it

because we took the plain

thoughts from our own heads

into the square, and spoke.

Yet a few blank pages later, Askew’s real conclusion in ‘Foreplay’ observes, ‘He’s told me to, so I’ll wait, and wait, and wait.’ Her collection is Achillean in nature – a short-lived, sudden blaze of self-empowerment and growth through which she explosively expresses wrath and rage towards injustice, and asserts her identity in a world of institutionalised oppression.

Orla Davey

Leave a Reply