Migrations: A field study of adversity

Until 29 October, 2022

Meffan Museum and Art Gallery, Forfar

George Lakoff writes of metaphors—understanding and experiencing one thing in terms of another—that they are a form of “embodied thinking”, a discursive tool by which abstract concepts, thoughts and feelings are grasped and understood through the concrete and the everyday. Sometimes addressing traumatic events not directly but at a slant defamiliarizes in very insightful ways. And so it is with Derek Robertson’s thoughtful exhibition, Migrations: A Field Study of Adversity, which employs the conceit of birds migrating—their lines of flight across borders, the dangers attendant on their journeys, their vulnerabilities, and also their will to survive against the odds—to address some of the difficult issues around the plight of refugees from which we, in our comfortable homes, might routinely avert our gaze.

Roberston specialises in painting wildlife. His recent Fife Open Studio in May 2022 contained some superb studies of badgers, deer, pigs, otters, and above all, avian life. Patient watchfulness of the often overlooked ordinary lives of birds, whether feeding, nesting, in flight mid wing-beat or coming to land, are translated into form and colour in quite extraordinary ways. That element of eye-witness, gleaned from years of ornithological study, is rendered in exquisite (mostly) watercolour studies which capture light, texture, feather and movement… which catches, for example, that delicate stillness of head when a bird is on alert. Some appear as worked up sketches with side notes, testing out different poses, and are as such imbued with a sense of the fleeting and the transitory. The common garden blue-tits, curlews or the more shy water rails appear on the canvas as if caught for a second mid-action; they could disappear at any time doing what they do in their unobtrusive lives.

How might the migrations of birds compare with human migration? In 2019 interview loaded up on YouTube after the original 2018 exhibition at the Pittenweem Arts Festival (attached below), Robertson speaks of an epiphany of sorts which suggested productive lines of thinking. He had seen boatloads of people crossing the Mediterranean ‘in obvious distress’ on television; some of the commentary surrounding these images had dehumanised them in ‘bestial terms… as swarms, as plagues, as rats, as cockroaches’. As an artist ‘compelled by imagery of wild creatures’, he thought to take his art practices—’using the same processes of research and representation’ for drawing birds—to paint people and situations in order reflect and connect with what he was seeing. The human migrants were ‘taking the same lanes of flight as the birds’ he’d been studying and drawing; the consequences of climate change also pushed them out of certain environments. After a year-long travel through Europe and the Middle-East painting and drawing, and giving workshops in refugee camps, Robertson worked up a series that drew on ‘the parallels between the bird migrations’ and ‘the real human distress of the people who have ended up in these desperate lines of flight’. And what a creative response this is…

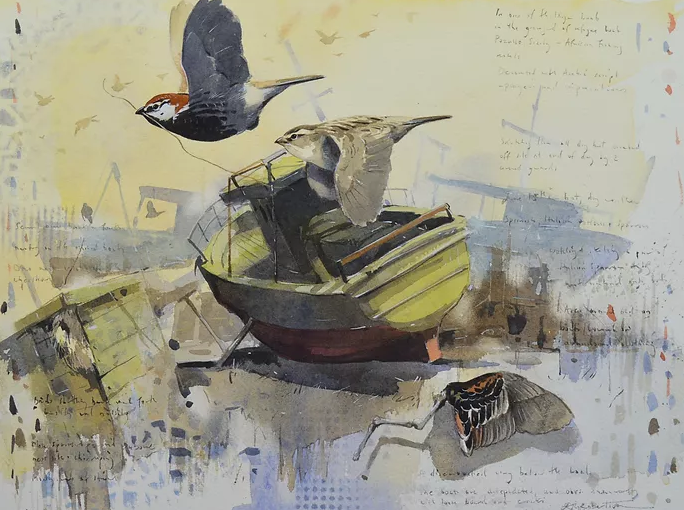

Migrations: A Field Study of Adversity is a poignant exhibition exploring not migration but also ‘homing’, ‘making a home’ as central to both animal and human life. In Nesting Sparrows, Grayeyard of Boats, Sicily, sparrows fly with odd bits of twigs in their beaks against a backdrop of abandoned boats and wrecks from refugee crossings. In Heart and Home (An Caim) set in the Outer Hebrides, the warming fire, rendered with a luminosity that only watercolour washes achieve, pulls a viewer in. This painted room is crammed with domestic objects—including socks hanging from a kitchen maid—yet at its outer fringes are shadowy outlines of deer, birds in flight and silhouettes of cottages. Interiors and exteriors coalesce, and memory finds form as an ache… as the pull of place. We make a home where we are, but we also remember… and bring stories with us. Inserting this picture into a larger exhibition about displacement creates questions about the ways people need homes and where they can find them (or not). If so for us, why not for others?

Graveyard of Refugee Boats also plays on light and shade; the darkness and shadows surrounding abandoned boats contrast with the delicate translucent yellow washes of the background, adding to the painting’s pathos. Propped up by support beams, rickety wooden boats painted in sombre blue tug at our conscience; the absence of human life here speaks volumes. Elsewhere, there are small studies of birds painted inside discarded box-like frames, (for example, Refuge Box). In order to generate a rawer presence, these shouldn’t really have been framed conventionally in glass and wood but left as they are; however, the paintings themselves suggest the cruelty of entrapment and incarceration powerfully. Birds are, of course, meant to be free—they move between borders.

Other paintings include the larger, visually surreal paintings such as When we Crossed The Dessert (a bird laden with boats, people and luggage); the Children of the Clouds where a fantasy figure stands upright, shrouded in loose desert clothing that seem to flap in the wind; and the very striking exotic canvases of red ibis set against Arabic-looking architecture and patterning. But for me the small avian studies steal the show. Here scale is used to signal beauty, fragility, determination and vulnerability all bound up together, and the various shades of brown used in the paintings suggest also a quotidian ordinariness that must surely strike a chord in all of us. Finally, the strategy of working up a painterly representation of the sketchbook, replete with writing as documenting (some texts are legible and others not) is perfectly pitched, hinting at the temporality of eye-witness, a proleptic sense of loss… the pathos of time (and life) never to be recovered.

Migrations: A field study of adversity now on tour at the Meffan Museum and Art Gallery takes seriously the art of witness. Take time to see, pause, imagine and reflect, and to see again for the exhibition reminds us that we—animal and human—share the same planetary spaces together.

Gail Low

Leave a Reply