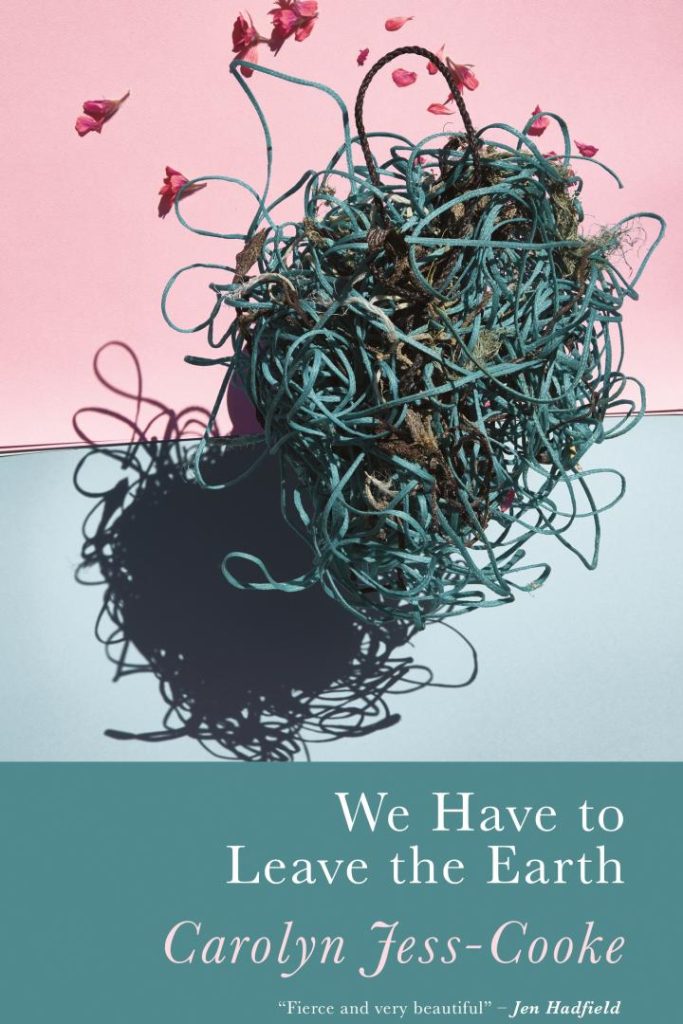

We Have to Leave the Earth

Carolyn Jess-Cooke

(Seren, 2021); pbk:£9.99

When a poet opens a collection quoting fellow-poet Ada Limón’s question,

Will you tell us the stories that make

us uncomfortable, but not complicit?

then already a great deal is being demanded of both the reader and of the writer.

Originally from Belfast, Carolyn Jess-Cooke now is very much part of Glasgow’s vibrant literary scene; she comes to We Have to Leave the Earth with a considerable backdrop of lived, researched and written experience. Pleasingly, her website describes her as being ‘not really bothered about genre’. That’s useful as the evidence of her ability to work beyond boundaries is clear.

There are four distinct sections in this book (although the themes invade one another). Each section seems far bigger, far more important than the page count suggests; every section has the assurance of a full project, fit to make a free-standing pamphlet or collection. Short, yes, but completely realised.

There’s something very courageous about prefacing the first part, ‘Songs for the Arctic’ with the poem ‘Now’. In the deceptive ease of a domestic setting where

my daughter sleeps by the dog, and I write of them only

because the folding away of light gives a voice

to what cannot be stilled [.]

Immediately, the poet meshes the globally catastrophic with the intensely personal, recognising fears and identifying responsibilities.

The sequence of poems following this engage with ‘the serrated wastes, wolf-winter,/ flukkra incessant as loneliness,/light pared to a foil[.]’ (‘Confrontation’).The experience of that topography is conveyed directly, from the typographic shaping of the poems, many in uncompromising double-spacing where whitespace dominates the textual layers. It’s impossible not to feel the arduous nature of arctic exploration in these lines, which contrast with the compacted layout of a neighbouring poem expressing hopes, sailing in the safety of a fjord, or in the elegantly controlled symmetry of ‘The Queen Aboard the Oseberg.’ Vistas are cinematic, the details precise, and the languages used throughout are as cutting as they are musical. The research (both historical and drawn from contemporary studies on global warming) lays down the gauntlet without compromise. Bravely again, the poet draws from the personal in the global in the final poem of this extraordinary sequence.

The second grouping charts the parental experience of the emergence of autism, and its attendant diagnostic process. She maps the repeated suppression of those worst fears, the impossibility of burying them, the medical confirmation and the subsequent self-interrogation and fruitless examination of the family tree. Jess-Cooke tells it truly.

The fears you believe in – know – are

coiling around your heart, your lungs

building up a muscle

you don’t realise you have.

(‘Things Will Work Out’)

These are far from graphic outspillings, and the poet’s formal care is as great as is it is in any other section of the book. However, as one who knows that territory well, my reaction was visceral. If a reader ever wants to understand how that time feels, they’ll find it described accurately in these startlingly beautiful poems.

The penultimate section’s nine poems, ‘The House of Rest’, celebrates the heroism of Josephine Butler. In a remarkable reaction to the accidental death of her own young daughter, Butler ‘threw herself into overturning the Contagious Diseases Act of 1869, which allowed any girl over the age of 13 to be forcibly subjected to a horrific medical examination of her cervix, and interned for up to a year, on mere suspicion of possessing venereal disease.’ (Notes). It’s a powerful read and ‘the only time/ the children are counted as treasure’ (Liverpool, 25th February, 1866), has prescient echoes as the US examines, or does not examine, its collective conscience on gun controls.

That final part pulls together strands, leaving that opening quotation entirely fulfilled. I cannot say enough about this significant collection. I can only urge you to read it.

That June, birdsong cleaved me

as rain splits drought, [.]

(‘Birdsong for a Breakdown’)

Beth McDonough

Leave a Reply