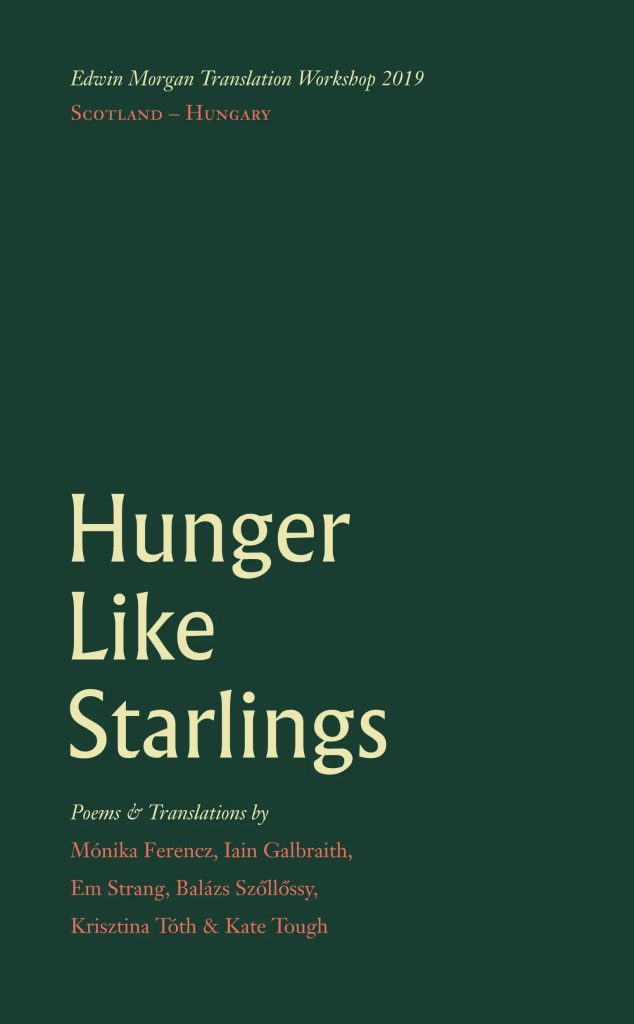

Hunger Like Starlings

Mónika Ferencz, Iain Galbraith, Em Strang, Balázs Szőllőssy, Krisztina Tóth and Kate Tough

Tapsalteerie, 2020); pbk £5

This insightful collaborative project, funded by the Edwin Morgan Trust and facilitated by Ken Cockburn in 2019, creates a firm linguistic bridge between English and Hungarian and explores what can be achieved through the art of translation. Having the same poem in two languages side by side on double-page spreads creates a real, tangible sense of collaboration. Even though an English reader might only understand the language on one side, the mirroring of enjambment, spacing and general rhythm emphasizes that no matter where we come from or what language we speak, we experience similar concerns. The epigraph of ‘Bird Woman’, ‘nothing is yet in its true form’, gives the sense that these poems are not yet at rest; this collection thrums with the anticipation of change and readjustment—with the potential to be reinterpreted and reimagined even further—thereby exploring the beautiful complexity and flexibility of language.

Through mirrored free verse, these authors and translators decipher each other’s concerns about temporality, our relationship with time, and with the fragility of human nature. Ferenz and Strang establish these central concerns in the first poem, ‘Cement factory in autumn’:

I kept hitting the concrete wall,

and realised my fist was made of porcelain.

This translation reflects the uselessness of fighting against time and death as humans reach instinctively for an impossibly divine sense of control. Yet in Ferenz’s original Hungarian poem, the last line is the shortest, thus showing how language and form changes in translation:

Ütöttem a betonfalat, és beláttam,

az öklöm porcelán.

The art of translation provides an interesting ebb and flow, as similar words and meanings create slightly differing lengths and overall structural shapes. It encapsules the push and pull of humanity as we struggle against the limits of time and lifespan. Ferenz’s narrator remarks that he thought his grandfather was ‘talking about my father, / but it turned out it was God.’ Throughout this collection we are shown the almost divine-like desire for dominance and control over our fates. The poems burn with defiance against loss, death, and intergenerational miscommunication as the poetic narrators grapple with the inevitability of degeneration and weakness. In the titular poem ‘Hunger like starlings’, Tough’s translation of Ferenz’s words defines this hunger as a desire for belonging as children watch:

their toys being hung on the grape vines

to scare away the damaging birds

of childhood.

These are the same children that were ‘setting off to look for / what became of them.’ These poems reveal how our sense of temporality and fragility are entwined with our desire for purpose and place. This hunger will only be satisfied when displacement and uncertainty is replaced with security, but collectively, these poets and translators convey how security exists only in spasms, engaged in a constant war with precarity. By bringing individual pieces of work as a uniting front, the collection reminds us that we are never alone even in the constant search for comfort and release. In ‘Columba,’ Galbraith depicts a ‘restless pigeon’ who is ‘splintered’ and searching for ‘a different land.’ Meanwhile, Strang’s ghazal ‘Doing bird’ states that ‘I show you white feathers’, yet ‘your stories unwing me.’ Their shared bird imagery reveals how even though we may never arrive at complete control and certainty, we are empowered by fortitude and forbearance. Whilst Ferenz and Tough observe in ‘Hunger like starlings’ that people ‘try to scour / from your gullet the names of the children with starlings’ hunger’, these poets stress the importance of embracing this yearning, as it defines what it means to be human.

Despite the potential for linguistic dissonance within these pages, the metaphors work effectively across both languages, thereby cementing similar human emotions and desires and exploring the complexities of our interconnected world.

Orla Davey

Leave a Reply