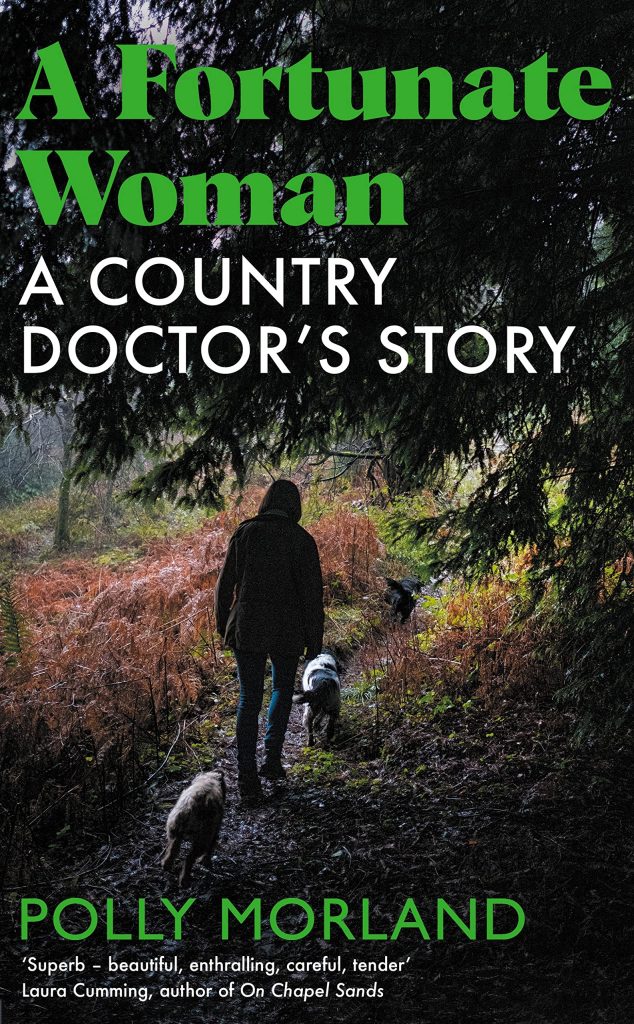

A Fortunate Woman: A Country Doctor’s Story

Polly Morland

(Picador, 2022); hbk: £16.99

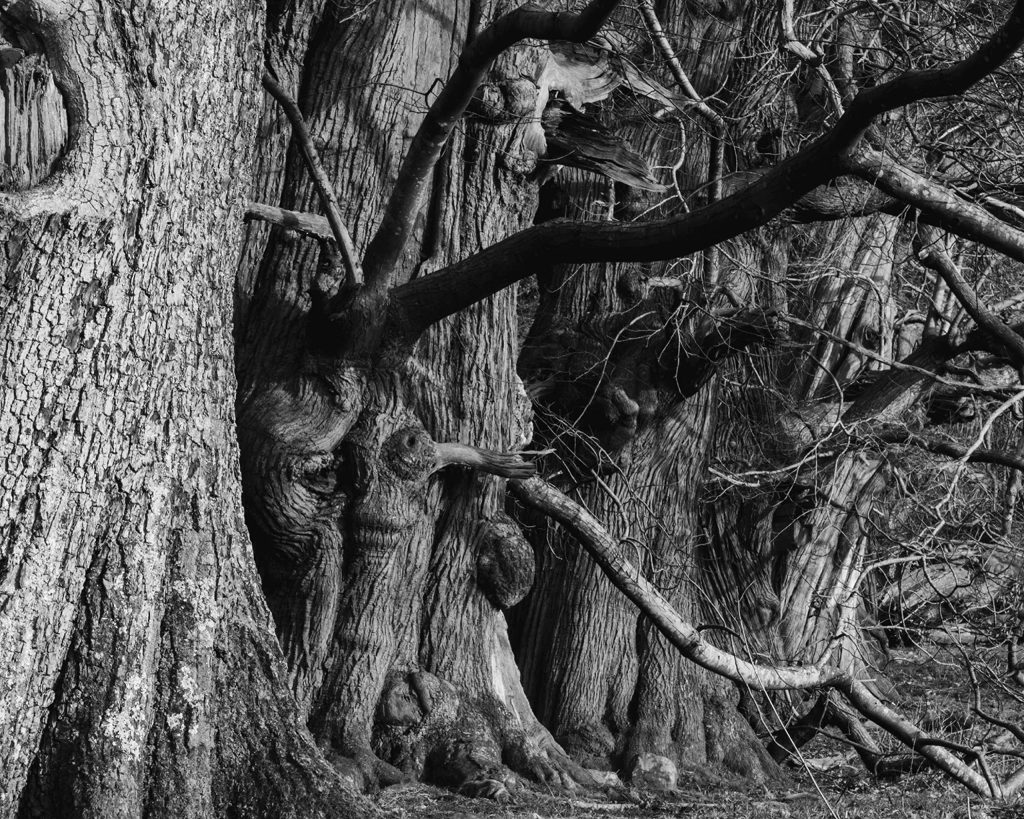

Superimposed onto a misty, monochromatic still in the ‘Prologue’ of Polly Morland’s fourth book, The Fortunate Woman: A Country Doctor’s Story, are words expressive of the primacy of place, the permanence of the valley, yet the provisional nature of the lives lived there: ‘A landscape doesn’t know who will build a life in its folds and undulations, walk in its paths, make breaths in the air.’

Morland’s book builds on the irony of first finding a copy of The Fortunate Man (1967) hanging ‘in suspended animation’ while clearing out her mother’s house, John Berger’s witness account of the vicissitudes of a country doctor’s life in the same Gloucestershire valley in which the author now resides. This find sets in motion a series of emotionally charged events pinning memory, persons, place to what it is to be a woman GP in a country practice in the last two years of Covid.

Unlike Berger’s doctor who was given the pseudonym of Dr John Sassalls, the unnamed protagonist doctor of The Fortunate Woman leads us through a landscape of case histories and much more: intimate spaces in which patients share details of their lives, their vulnerabilities, their health in crisis vis-à-vis the pandemic. In these various interactions, we learn about the real skillset of the doctor ‘approaching care with the same dedication, empathy and effectiveness.’ Through Polly’s luminous descriptions of the landscape, we connect with a deeper beauty, the allure of the past.

This double-focus, a perceptual bridging with Berger’s witness account, offers something more. A different way of looking and seeing perhaps. The quotidian of life in the valley, everyday illnesses and the medical emergencies occurring in the community, suggest an awareness about the interconnectedness of rural life. Critically, it offers a historical perspective on how country practice has been affected over time by policy changes within the NHS. Polly writes,‘He limps into the room, trailing a faint tang of sheep.’ In this instance, it’s a fractured leg. In another case, massive bleeding; and in another, a life-threatening arrhythmia. Through this way of telling, a combination of the observer’s voice and transcripts of conversations, we learn what it is to be this doctor in this country practice. But it could be true of all community practitioners. We learn of the diverse nature of the work, the time-critical decisions that must be made; the pregnant woman with vaginal bleeding and the young man with a dangerously low blood oxygen level because of a Covid infection who survive because of the doctor’s skill and empathy in understanding:

not just a medical history but also a personal history, a winding corridor of experience and emotion, the patient’s whole life […] talking to people, listening to their stories, every bit as much as it’s about clinical examination.

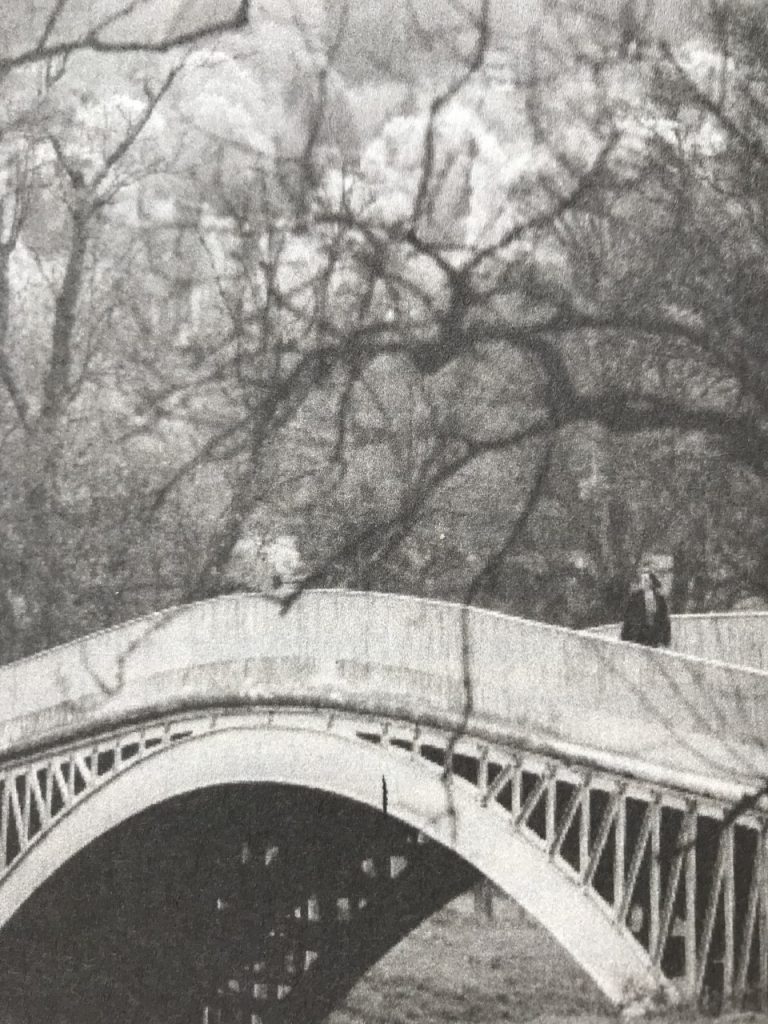

Photographic images by Richard Baker proliferate and are integral to Polly’s story – not only do they continuously link persons to places but they also link-up ideas not unlike a Möbius strip. One particular image depicting an off-road Range Rover deeply entangled in bushes and bearing the humorous forward, ‘(t)hese early years in the valley were all about finding her way as a doctor – in every sense of the word […]’, acts as a launchpad of sorts for reflection on life there in the valley as a ‘labyrinth’ with ‘little logic to their convolutions, bifurcations and occasional dead ends […]’. Another portentous image is of the doctor on a bridge looking outward; many more with her donning mask, visor, gloves and apron treating patients at the height of the pandemic in a variety of locations, engaging with them as persons.

Beautiful and fascinating then. Beautiful in the way it combines the structural elements of storytelling with the skill of real-life reporting, clustering them in the brilliance of a cloisonné-finish. Fascinating how it visualises the past through its frequent references to John Berger’s story. An intensely enjoyable read.

William Hume

Leave a Reply