A Democracy of Poisons

Tim Allen

(Shearsman Books, 2021); pbk. £10.95

Squirrel made of seven black holes repeats the pattern on a pincushion but the needles are long gone shot at light speed towards the eye of the deity.

(‘30. Line’)

Tim Allen’s A Democracy of Poisons, his third collection with Shearsman, possesses rich, surreal imagery—visions that float or collide with the reader, betraying his avant tendencies. However, his dreams aren’t pleasant—they’re anxious, tense:

I walk into a narrative I don’t run I don’t crawl or creep I casually insert my self into the forest.

(‘1. Walk’)

Allen’s collection seems frantic—prose poetry with extremes of punctuation and morphed writing structures create work that is bare, raw, and nightmarish. Both clear and vague simultaneously, his visualisations crash as seemingly nonsensical pieces; in ‘3. Growing’

It is growing cold. The cold grows rows of black puddings but residual hotcakes linger in the puddings long after the potlatch. We lack for no reason. Our blood sausage is made from blankets.

Yet just as he embraces contradictory phrasing, Allen’s ideas seep out—political unrest in a barricaded Parisian street in ‘27. Who’; the paradoxical ‘blank space for your personal message’ in ‘39. Mammals’; hints of his personal experiences going to the 1982 League Cup Final with ‘Labour Party racists’ at a time when there were ‘no black and brown in Plymouth.’ (‘54. In’) In such a manner, his forward thinking, unconventional writing puts him at odds with conventional, conservative Britain.

The confusing and unpleasantness of Allen’s rapturous collection is captured by Andrew Duncan, quoted on the collection’s blurb. The title evokes a ‘camaraderie of bad ideas’; ‘a 24-hour media slew in which toxic ideas try to win popularity contests.’ Duncan emphasises Allen’s fearlessness of awkwardness, his unrelenting writing opening ‘a new world, with new conventions.’

Allen’s life in Plymouth, before his moving and engagement with the ‘avant wing of the North-West poetry scene’ (collection’s blurb) of Lancashire, has him imbue his collection with frustration. Anger simmers, manifesting in his rant-like poetry, building up as each piece interacts and follows one another, and appearing in depictions of failing civilisations.

a one-eyed waterfall where exposed pipes shirk work and shredded pools trickle to a damn of tat, the path ending in a dank tunnel beneath our improvised civilisations one-lane bridge.

(’44. Life’)

Other pieces, such as ‘48. Old’ support this: a city where the ‘devil is not in the detail it’s found in the sprawl’; unchecked developments spilling across the landscape. Here a rotten underbelly is covered up, in ‘blitzed-out night bebops’, where the ugliness is obscured despite ‘Poison drizzle’ and ‘Poetry is screwed on.’

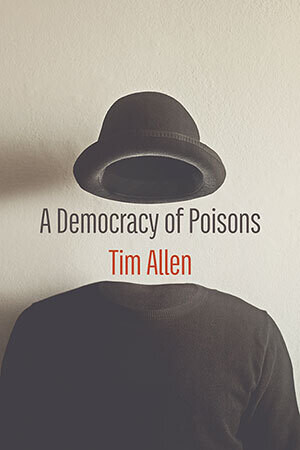

In the same poem, Allen betrays the source of his collection’s cover; Rene Magritte’s ‘Bowler Hat.’ In so doing, he calls on Magritte’s use of the bowler hat as representing an anonymous ‘everyman’.

A professional has style even when on his knees he grazes with the cattle

(’49. Luck’)

The collections cover is apt—a neatly dressed invisible figure. Nothing beyond surface level ‘decoration’, the hat also evokes a particular idea of English gentry out in their Sunday best.

‘63. Extreme’ captures the core of his collection, and of his frustrations:

A Titanic lounge where a poker game continues as cool as cucumber even as the table tilts

a wealthy, hubristic Britain having fun whilst everything collapses around them, finery dissolving into ruin.

Allen’s work (apparently) betrays itself with self-conflicting self-reflections:

The prose poem is a mindless form, the perfect vehicle for someone supporting democracy […]

(’72. Prose’)

By ‘demeaning’ prose poetry, he admonishes his own collection. Yet his work, imbued with real frustrations and feeling, is clearly mindful. In doing so, has he made his nonsensical rhetoric more cerebral and meaningful than conventional poetry? Duncan believes so.

Allen’s work demands the reader to pay attention, to read and re-read, to enter the depths of his grounded surrealism… much like a sea which swallows even the Titanic.

James McLeish

Oooo I’m so glad you enjoyed it James MacLeish. You have made me want to read it again.