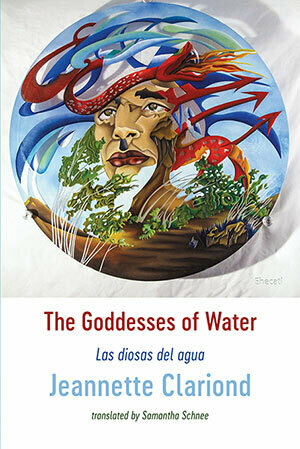

The Goddesses of Water

Jeanette L. Clariond. (Translated by Samantha Schnee)

(Shearsman Books, 2021); pbk: £12.95

A good book can seem to slow time around us, allowing us to settle ourselves into its pages. Jeanette L. Clariond’s The Goddess of Water transmogrifies reality, bringing the reader into her world and holding them long after they have left the book behind. Clariond has published many collections and her ability to not only write poetry but craft it into such a deliberate, thoughtful structure speaks to her experience. Every page proves a maze, drawing the reader in and leading them through the rich tapestry of Aztec myth, spoken with striking lyricism and intertwined skilfully with the all too contemporary subject of femicide and gendered violence in South America.

Rather than having a list of poems, The Goddess of Water has five sections, with one or multiple unnamed poems, each employing a different style and layout. This is likely a nod to the Aztec creation myth, which is known as the Tale of the Fifth Sun. The myth describes the creation and destruction cycle of the world, with our existence being a part of the fifth of these cycles. The first four sections of poetry describe the mythology of a former empire. The fifth section of poetry, much like the fifth cycle, is contemporary. This framing device also allows the Author to explore multiple interpretations and composition styles for the central mythos. All the English translations of the poems are accompanied by a copy of the original work on the left facing page and the English on the right. Both translations use words in Nahuatl when describing concepts, objects, and living things that are of cultural importance. While the original language text is a much appreciated addition, the book unfortunately lacks a pronunciation guide, so in this instance I would recommend looking up the Nahuatl vocabulary spread throughout the text. The pronunciation is key to the embouchure of the work and plays beautifully with the English translation:

It was the year 13 Pedernal.

In the morning the teponaztles

Accompanied Axayacatzin’s songs.

Perdernal: Pay-dare-nal

Teponaztles:Tay-po-nawtz-lee

Axayacatzin: Ex-aya-cats-in

The first of these sections, ‘Antecanto’, utilises a prose style that follows the tradition of oral storytelling. These pieces also use the long form structure to expand on the historic, cultural and philosophical discussions of the collection. Who Were the Goddesses sets its focus on the story of Coyolxauhqui, goddess of the moon, expanding on the mythos that roots the book in place. The ’52 Fragments’ are a series of fifty-two tercets, each portraying an image of nature important to the themes of the work and the Aztec faith. As an artist who works with images, this was a personal favourite, it’s heartening to see such concise language used to paint such an exquisite portrait of nature was fascinating to see:

The cochineal torn from the nopal

Discharges its deep red

Then the goddesses sketched their bodies in the book [.]

They cease their song employs couplets, using surreal imagery and jazz-like rhythm to blend religious scenes with stories of loss, violence, and dysphoria of the modern day. Finally, Postcanto, the final piece dwells on the ongoing violence and abuse that women face,

The Redness forms a sediment in the heart.

Let’s rush to raise a song for these dead women

for whom no one will be held accountable.

Blind eyes of stone, blind hands, Have Pity!

a reflection on the collective mourning that seems to go unheard.

As with so many great contemporary poetry collections, the book lends itself to being read in chronological order and certainly rewards the reader for taking the time to experience the work as a single large-scale piece. However, each poem can, and should also be taken as self-contained works. Each realises a space, emotive and commanding, that underpins the ability to remain distinct in the face of such a long body of work. Like the slow, deliberate beat of a drum, the pieces sound themselves out, with grammar and spacing skilfully used to direct the mind through the composition and melody of the work. The ‘52 fragments’ in particular offer very compact inflections of sound, precise language and lush imagery to echo through your mind as you are brought through this world that Clariond brings to The Goddess of Water.

Ellen Harrold

Beautiful review of a deep read book, Ellen.

Really can’t wait to read collection after reading excellent review.

Thank you, Tina, it is an excellent review and an excellent translation. My kind regards, Jeannette