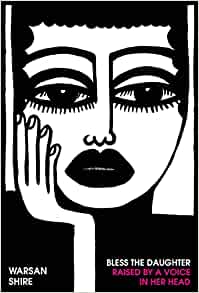

Bless the Daughter Raised By a Voice In Her Head (Shortlisted for the Felix Dennix Prize for First Collection)

Warsan Shire

(Penguin Random House, 2022); hbk £12.99

Somali-British poet, Warsan Shire draws us into the complexities of the transition from girl to woman, immigrant to citizen, in this, her much awaited and first full collection. With an array of accolades which include her much circulated and highly influential poem ‘Home’, and her work with Beyoncè Knowles-Carter on the Album Lemonade, this much awaited collection is written with sensitivity and without pretence.

The title of a poetry collection tends to be the nail from which the works are hung, but the inaugural poem, ‘Extreme Girlhood’ is that nail; Shire encapsulates intergenerational trauma, in three succinct lines:

A loop, a girl born

to each family,

prelude to suffering.

Italicised lyrics chime in a dichotomous weave of pain and suffering as Gloria Gaynor synthesises in our minds, ‘At first I was afraid, I was petrified[.]’ A sense of strength and resilience takes hold as the mind filters through and we connect; the allegory is instinctual, evoking a feeling of empowerment and emancipation as this concerto of confidence resounds in the ears of all women, irrespective of race, age or displacement.

Shire deftly crossfades English with her native Somali as we consider her world:

The child reads surahs each night

to veil her from il[.]

The assonance of ‘veil’ and ‘il’ (the evil eye in Somali culture) is no coincidence, this is a demonstration of Shire’s technical agility that renders the narrative of this assemblage alive across all four sections. The howling elongates into a cry of fear as the speaker (Shire)

[…] wakes with a fright,

[…]

something creeping

deep inside her.

The influential and reworked poem ‘HOME’ lays bare the fallacy and social predicament of refugees; do they enter the western world to freedom? No. Instead. to prejudice and ‘prison everywhere’. To believe that a person ‘would choose to make a refugee camp home for a year’ is an absurd choice. What would any of us do if ‘Home [was] the barrel of a gun’? The new addition, part II, brings the corporeal experience of the female asylum seeker to the fore. Cast adrift ‘longing’ to ‘belong’, their home ‘disappearing’, their ‘beauty is not beauty here’.

In ‘ASSIMILATION’ we recoil as:

[…] the refugee is asked

are you human?

Depersonalised and objectified to ‘it’, self-loathing manifests as an eating disorder and riffs through ‘BLESS THE BULIMIC’. ‘The Famine back home’, is personified as the speaker pleads shamefully ‘forgive me’.

Yet, what chance does a child have to flourish if mother is absent in presence or mind? The epigraph ‘AFTER IDRA NOVEY’ in ‘HOOYO ISN’T HOME’ lays bare the legacy of stolen childhoods,

While our milk teeth were forced down our gullets.

This startling imagery is mixed with a high register that sticks in our throats:

While the statistics show 1 in 3 girls, 1 in 5 boys.

Subordinated conjunctions act as threads of traumatic memory gathered in a single point of time, disconnected from emotion as mind is from body before it ‘breaks’:

When the body remembers, it bucks wildly.

[…]

While you wash your body you realise it is not your body.

And at the same time, it is the only body you have.

But where is father? Motif and tone are beautifully juxtaposed in ‘LULLABY FOR FATHER’ which opens with soft Somali assonance:

Soo bari, aabo […]

Here, Shire draws on the metaphysical. ‘Children’ are ‘distant galaxies’ while father ‘hang[s] on the edge of the moon’, as unreachable as innocence lost. There is pain, regret and anger in the gentle, wistful tone, as ‘dreams [are] macerated under grief’s gaze.’ But even Aabo was innocent once, as was Hooyo and the generations of Africans scattered by ‘the white gloved hand of Europe[.]’

This collection is not a diatribe. As an exploration of patriarchal legacies, it is an education that urges us to question the manumission of then and of now.

Wanda McGregor.

Leave a Reply