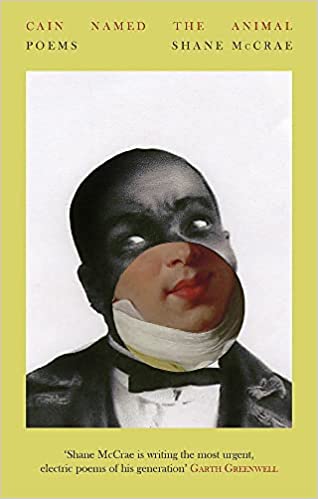

Cain Named the Animal (Shortlisted, Forward Prize for Best Collection)

Shane McCrae

(Corsair, 2022); pbk £10.99

There are cracks running visibly through the poems in Cain Named the Animal. From reading reviews of American poet Shane McCrae’s earlier collections, National Book Award Finalist In the Language of My Captor and T S Eliot prize shortlisted Sometimes I Never Suffered, cracks persist throughout them too as well as no punctuation with space instead serving as a kind of punc- tuation coupled with stumbling repetitions stumbling and the odd / line break depicted odd as you would write it in an essay or review. it is an arresting device and one that initially to me, initially was a distraction seeming to get i n the way of me hearing the poems in my head.

But those spaces stayed with me. Turned initial feelings of annoyance and frustration that I wasn’t quite getting it or maybe it was just an artifice with nothing ‘to get’ into something else. It made me revisit the poems: in various moods and states of tiredness.

Cain Named the Animal is McCrae’s eighth collection. Divided into three sections, the second, entitled ‘Recapitulations’ and the third ‘Cain Named the Animal’ continue ideas begun in an epic poem in earlier collections. Evoking Milton, McCrae revisits the characters of Jim Limber and the Hastily Assembled Angel, adding new creations such as the Lost Tribe of Eden and a talking robot bird. These sections have a very dreamlike, incantatory quality, and at their best evoke the likes of Ginsberg. At the same time, while the stories such as that of time entering the Garden of Eden intrigue, I am not entirely sure what to make of them.

The same cannot be said of the powerful first section, ‘Love Poems and Others’. These draw heavily on McCrae’s own remarkable story: born mixed race, his maternal grandparents—who were white supremacists—kidnapped him aged three, lied to him that his black father had abandoned him, and subjected him to physical and mental abuse. With this in mind, the visual metaphor of cracked poems begins to make sense and several of the book’s most powerful moments concern these people and events. ‘Worldful’ reflects first on the passing of time since his grandmother died, before the speaker catches sight of an old man on the metro who might just be the grandfather that he has not spoken to for twenty-eight years:

I wanted to rise from my seat

And throw my arms around him and to not

Remember why I want to never speak

To him again I wanted to and then

Remembered why I want to never touch

Him or be touched by him again instead I watched[.]

‘Whom I have blocked out’ is about the memory of being thrown from a horse, but as the speaker tells us, ‘I trusted what men said was gentle / to hurt’, there seem to be other traumas being repressed. In ‘To Make a Wound’ McCrae addresses his grandmother directly: ‘I know I should feel wounded by your death / I write to you to make a wound write back.’

Other highlights include ‘Arm in the Excavator’s shovel’, where the white space in the poem suggests the shape of bones in the earth itself. ’The Butterflies the Mountain and the Lake’ takes for its subject the path monarch butterflies fly whilst migrating south over Lake Superior, turning half way to avoid a mountain that disappeared a millennia ago. In McCrae’s work, heightened situations and descriptions contrast with vernacular to great effect. In my favourite poem, the overtly political ‘Some Heavens Are All Silence’, McCrae addresses ‘y’all got a heaven just for y’all’

…listen

Bow your head that is the voice of God that breath[.]

Kate Kellaway asserts of McCrae that “The pauses in the poems are political: they interrupt the narrative, the stalling powerfully suggestive of an imperfect freedom of speech.” For me, the cracks do this and more: evoking personal trauma, the inadequacies of language, moments of silence, and being silenced. From what at times is a transcendent collection, the cracks in Cain Named the Animal have stayed with me.

Stephen Carruthers

Leave a Reply