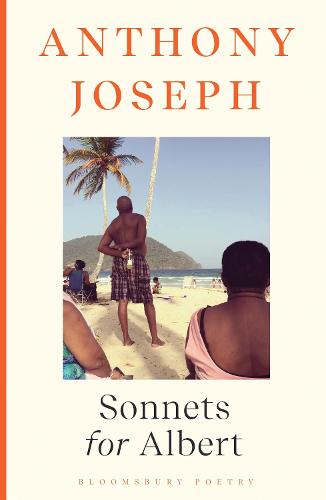

Sonnets for Albert (Shortlisted, Forward Prize for Best Collection)

Anthony Joseph

(Bloomsbury Poetry, 2022); pbk; £9.99

The sonnet is a design classic; it retains its formal appeal, with contemporary giants such as Don Paterson and Imtiaz Dharker regularly inspired by its elegance and infinite variety. Trinidadian poet Anthony Joseph has used the form to explore his relationship with his father and with himself across a sequence of more than 50 poems.

Joseph identifies his14-liners (though he takes poetic liberties with the form in places) as ‘calypso sonnets’, drawing their influence in part from the musical/spoken word style popularised in 20th Century Caribbean traditions. This might be seen as a channel of connection for Joseph – speaking with the rhythm and register of his late father is perhaps a way of sparking memory.

Albert Joseph is brought to detailed life through fragments of memory, but the sequence begins with the hours and days immediately following his death, starting with that dolorous journey that many bereaved offspring have to undertake,

When I hear my father dead

I flew ten hours into the sun.

Next morning I put black on[.]

This opening sonnet sets out the poet’s approach from the start – ostensibly simple language but laden with clear metaphors for loss and mourning or, as they state bluntly in the poem ‘Shame 2’,

Everything is symbolic in literature.

What waits at the end of the journey is no less hard than the anticipation of it; in this case, Joseph’s father in an uncharacteristically dishevelled and distressing state,

The balls of his fists were at his side,

stiff as the bag he had been zipped into.

and,

He certainly would have been ashamed

for anyone to see him this way,

with teeth protruding.

The need to give his father dignity unfolds over the next 90 pages in a way that humanises rather than canonizes. He attempts to draw aside the veil of simplicity that his father habitually wore when in his children’s presence. The essence of that uncomplicated front is alluded to in ‘Paramin’,

I saw that within the simplicity of the life Papa God gave him,

to work, fuck and pray was sufficient.

Bereavement often leads us to seek the essence of who and what we have lost. Joseph recognises that parents often hide their true selves from their children and looks to assemble his recollections of fragments of personality into a clear picture. Anecdotal and incidental memories feel as vivid as the more considered observations; alongside an extended criticism of his father’s promiscuity in ‘Broadway’ there are tiny flashes of Albert in his dirty jokes, gambling and attention to style bordering on vanity. The poet does not flinch from describing his father’s failings, sometimes observing and recording, other times striking up a rueful and occasionally bitter conversation with the departed.

The sequence climaxes with the funeral rites described in ‘The Tumuli in Santa Cruz’, with Joseph’s eye for the minor details that tell the bigger story once again to the fore,

The long hearse purred in the sloping yard. Perfume sang from the bosoms of aunts and far cousins.

And finally, the camera pulls back for the wide-angle image that draws the sequence to a close,

We shall all be rooted in this well of hours, eventually.

Interleaved between the sonnets is a series of black and white photographs depicting his father in a variety of settings across his life. As a whole, the book is an effective scrapbook of image, anecdote and observation that successfully breathe life into the myth and reality of a parent and what is inherited from them. As a study of both Joseph Snr and, by extension, Joseph Jnr it is accessible, honest and rich with rhythm and soul. It feels like a book that, the poet was compelled to write. That it was written with such precision, depth and warmth is a testament to both the poet and to the complex father who inspired it.

Andy Jackson

Leave a Reply