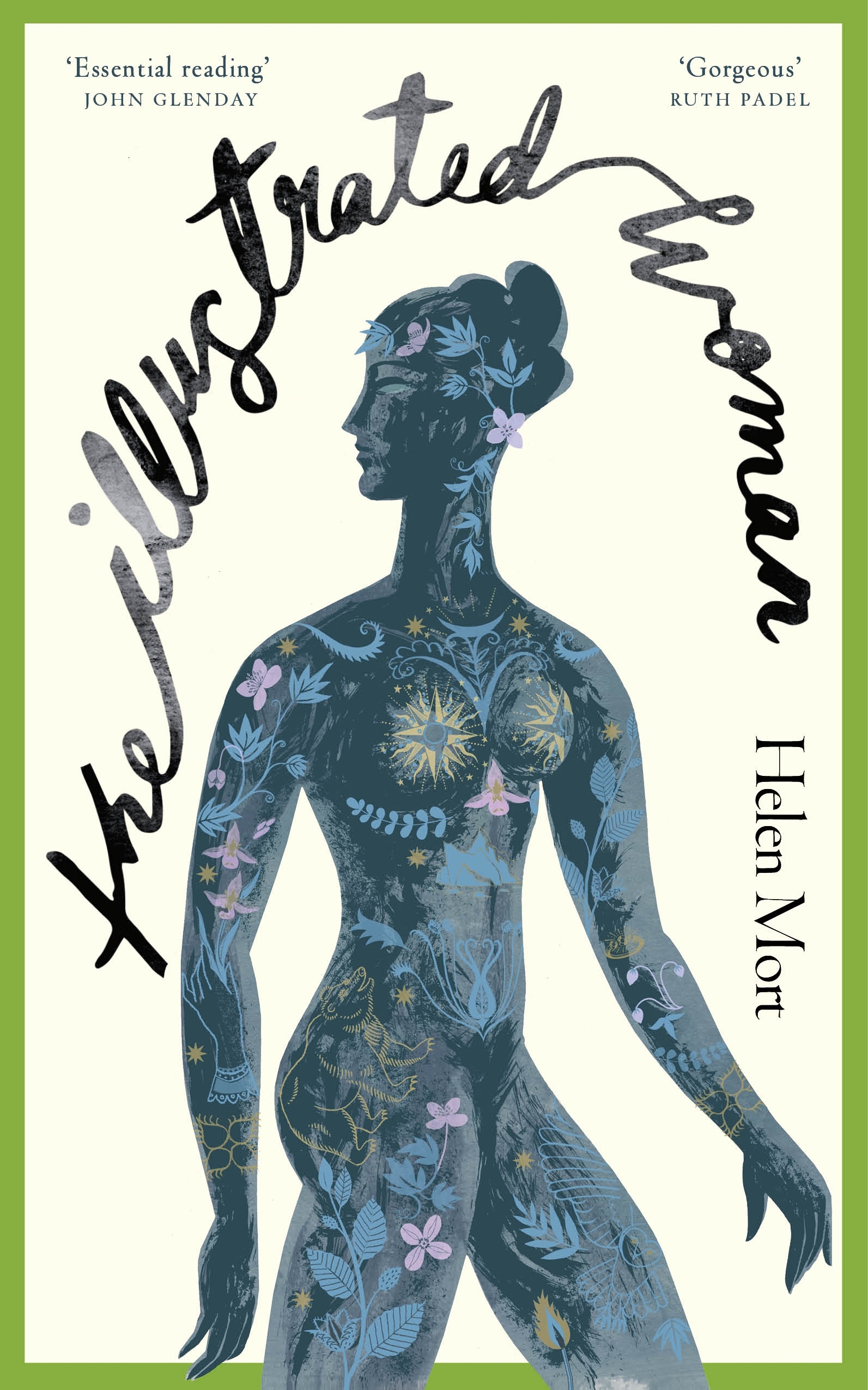

The Illustrated Woman (SHORTLISTED, FORWARD PRIZE FOR BEST COLLECTION)

Helen Mort

(Chatto & Windus, 2022); pbk, £12.99

I picked up this title initially because I still blanche whenever my daughter shows me her new tattoos; but I also heard Helen Mort’s very interesting exchange with Lou Hopper about ‘getting inked’ on Radio 4’s One to One in February last year. Mort is, of course, an award-winning poet that is based in Sheffield and whose interests take in an astonishing range–mountain climbing, trail running, northern cites, conflict and motherhood—all handled with a sure and delicate lyricism, and a poet’s ear for the cadence and fall of the line. So The Illustrated Woman promised much.

Beyond its more obvious reference to tattooing, the choice of collection’s title catches the word ‘illustrated’ in the sense of display and information. But Mort’s is different. How and in what ways can one illustrate woman? Mort’s explorations of what and how we see women, and by extension what we can’t or don’t see, form a richly textured thematic strand throughout the collection that takes sexism, voyeurism, pornography, love, maternity, feisty women inked women who ‘designed’ themselves, but also women who have had to trade their bodies for cash. The narrator inhabits each of these portraits imaginatively, reflectively, sympathetically—like the wearing of a silver ring passed down between grandmother, mother and daughter in ‘Precious’:

I put my fingers through

and I am entering their bodies, gently —but I will carry its coolness, the ache

of near invisibility….We are born bright and we burn

down to the precious metal of our bones,ashes to ashes,

flawed gold to gold.

The collection’s tripartite division—’skin’, ‘skinless’ and ‘skinned’—is inspired. It encourages us to ponder on skin’s metaphoric associations: as surface, a liminal border between what is inside the human body and what’s outside. Skin can feel and record the impact of the external world (the phrase ‘thin skinned’ gestures towards this); skin can also be marked deliberately or accidentally in tattoos and scars. Skin is thus as much the body’s membrane as a boundary. The collection plumbs the subjective interior as much as it describes exteriors; in ‘Rain Twice’, love and reciprocity finds itself in the image of falling rain soaking the skin into a translucent transparency, ‘held to the light’,

so you can

see right through me,

how I break

and make the world

seem solid again.

In ‘Recurring dream’, the inked illustration gets up ‘stretches her limbs, extends one foot/then disembarks your leg and walks into the world’. Change, movement and a porousness between landscapes outside and the landscapes of the mind haunt these poems with an emotional charge that is enhanced by Mort’s ability to handle description and images to suggest, project or introject emotions. Much is risked in love poems about Alfie her son, but the boldness of her ‘skinless’ venture pays off. For why shouldn’t women write about that intimacy between mother and child? ‘Truth is a milky thing’. The collection’s tonal changes also allow for different key signatures such as the marvellously clever and sly ‘A Well-known Beach’, where repetition of key word clusters and their changing placement in the line brings the message home of how tattooed women are stereotypically perceived by men. And in poems about pornography, and about Mort’s own experience with deepfake images of her used to create violent pornographic images online, much more distressing and disturbing notes are sounded—and also resisted:

This is you doing your worst.

This is language reduced to words.

This is me using you hard in a poem

where I decide what’s shown.

In The Illustrated Women then, words and inks are used to tell stories ‘skimmed over too long’; this is a collection

Chosen to surface

what’s inside and wear it brightly.

While Mort’s collection may not assuage my fear of my daughter’s hoard of tattoos growing, it does go a long way to bear witness to being a woman in complex ways that are full of head and heart.

Gail Low

Leave a Reply