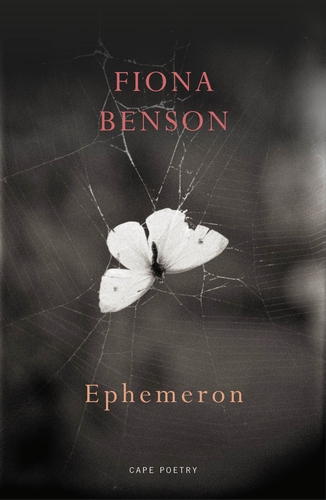

Ephemeron (Shortlisted, TS Eliot Prize)

Fiona Benson

(Jonathan Cape, 2022; pbk: £12)

[…] She sang, and all the hurt

and beautiful universe, all the souls

came crowding in.

(‘Edelweiss’)

If the title Ephemeron conjures insignificant transience, that would be a misreading. Fiona Benson’s most recent collection examines the fragile, the momentary, the nearly unseen, all of which merit observation, understanding, and a permanent record.

Divided into four parts with seemingly disparate subject-matter, ‘Insect Love Songs’, ‘Boarding-School Tales’, ‘Translations from the Pasiphaë’ and ‘Daughter Mother’, the poet uncovers interconnections between them. The subtlety of that structuring and sequencing feat is remarkable.

Benson’s study of insects combines the rigorously scientific with the lyrical. From the outset, her use of form is integral to the content’s anatomy. Consider the unbroken density of ‘Mosquitoes, Mozambique’, summoning humanity’s swarmed-around fears, even before the ‘How we collectively itch’ opens the poem’s malaria ward narrative. Elsewhere, there are the fly lightnesses of staggered, spaced tercets, and assuredly tight couplets on couplings in a series which knows the cycle of love, sex, nurture and death in senses that far transcend the simply anthropomorphic. Brava to the poet too for addressing her private phobia in extraordinary lines to the maligned creature in ‘Mama Cockroach, I Love You’. ‘Someone must care for the dirt’.

Currently, arguably there is a certain knee-jerked reaction to privilege and if the opportunity arises it’s worth hearing Benson address her own wisely in her introduction to ‘Boarding-School Tales’ at a performance earlier in the year. Anyone reading this book enjoys at least one form of privilege. The problem is surely when there’s a lack of awareness, and the poet is scalpel-bright in dissecting her own past. There is that glorious understanding, both positive and negative, of the nature of passing through adolescence in an all-female environment. The evocative ‘Like a Prayer’ encapsulates the urgency of emerging sexuality whilst limbering up at the school show, in a toothy poem balancing seriousness with humour. Think what Lisa McGee achieved in Derry Girls, and Benson’s ‘sexed-up church’—channelling Madonna—does it perfectly in five packed quintains. I was fortunate enough to attend Benson’s reading from Ephemeron early this year and apparently the final poem in this section, ‘Boarding-School Crush # 17: Wonderwall’, gives her own mother issues as her straight daughter writes graphically of her teenage pash. Nonetheless, the poet reads this at all readings from Ephermeron, honouring the LBQTI community still facing far worse terrors.

W.N. Herbert suspects that there comes a time in any serious poet’s development when there’s a need to re-visit the ancient texts. In ‘Translations from the Pasiphaë’ Benson interprets the Minotaur myth, considering the possibility that the sorceress Queen of Crete’s son, Asterios, is not a beast but a child ‘with a disability or deformation’. The poet’s end notes quote Aristotle and the consequent practices

of exposing unwanted children [left by the roadside] is thought to have led to the

deaths of countless disabled children, as well as extraneous, and perhaps most often female, children.

Pasiphaë is the abused, the defiant, the ultimate protector of her beloved son, who is also subjected to her husband’s intense cruelty, society’s mores and darker gossip:

I could no longer hold office at the temple

for fear I would defile other women[.]

(‘Pasiphaë on her Denouncement’)

In ‘Ariadne: On my Brother’s Falling Sickness’, we hear how

each upper eyelid

flickering, the tremor that built to a drumming

of heels[.]

grow in his sister’s understanding, draw out her role in his death and her consequent grief, ‘You didn’t know me; you didn’t know yourself’.

There are too may wonders to quote adequately in Ephemeron. As the mother of a son with a disability, I found these poems harrowing in the extreme, and absolutely brilliant and right. Few people lacking direct experience could write and convince me. Fiona Benson does.

After that, the shorter concluding section Daughter Mother was needed; it relives early, anxious motherhood and its hopes, perfectly.

Benson avers that Kim Moore’s last collection should become canonical. It should. The superb Ephemeron is at least as deserving of that same status.

Beth McDonough

Leave a Reply