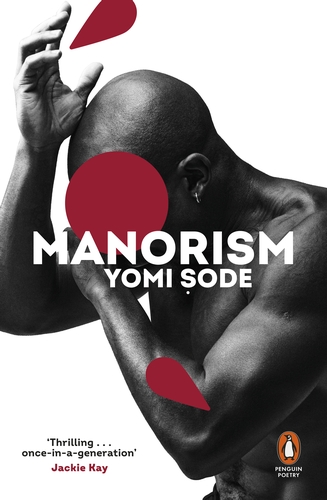

Manorism (SHORTLISTED, TS ELIOT PRIZE)

Yomi Ṣode

(Penguin Poetry, 2022); pbk; £12.99

The working poet is required to remain on duty, ready for the moment when they are inspired or moved to write. In the case of Yomi Sode, this role is more proactive, requiring the poet to actively sift the airwaves and social media in search of those who wish to ignore, belittle or simply redact the spoken and written experience of black lives. This is a draining but necessary responsibility, and one which Yomi Sode takes seriously in his collection Manorism in which he rails against the slave trade, white privilege, the scandal of Grenfell and Police brutality. He quotes from the reactionary observations of Piers Morgan, Dominic Raab and historian David Starkey, from conversations on Twitter and radio talk shows;

A year later, I’ll read

Slavery was not genocide, otherwise there

wouldn’t be so many damn blacks in Africa or in

Britain, would there? – David Starkey.

No-one is allowed the benefit of the doubt – nor, given the seriousness of the issues in question, should they be.

Given Sode’s watching brief on media oppression, one might think his poetry may be bitter and exclusive, particularly to readers like myself who haven’t been subject to the same prejudice. It is, however, balanced and layered, leavened with beauty and eloquence. It is lit from all angles like the works of Caravaggio which are referenced throughout, not flinching from the ugliness of oppression but showing it to us in painterly detail. It shifts from rage to tenderness in a beat, evidenced in ‘Confessions of a Penitent’ where Sode displays shame at his inability to face up to serious illness in a loved one;

Most days, I failed. I watched the phone like a

hatching bird in my palm. I did not call.

He recounts with barely-restrained anger his experience in a restaurant where he is required to pay for his food in advance while his white fellow-diners do not;

That evening, I too dreamt of violence. I no longer

had the benefit of the doubt to give.

I imagined pulling that waiter’s tie in over a lit

candle. I imagined holding him there, his throat

hovering over the flame. I pressed the final digit

in.

The poet interweaves English with Yoruba and street slang and is also happy to invent terms for the emotions he and many others experience that have no name. One such term is ‘aneephya’ which he describes in a BBC interview as “the stress toxin of inherited trauma, which leads to fear, violence and sometimes death”. Manorism, the title of the collection, is itself a neologism, standing for the attitude of mind that comes from the place of one’s upbringing – one’s ‘Manor’. This attitude manifests as a survival instinct in the face of oppression, and a necessary suspicion of the motives of authority. Even if the reader does not identify with Sode’s experiences, there is much for the empathetic to get angry about.

Poems range from lyrical, occasionally formal, to prose pieces that feel like they were written for the stage, an environment Sode is comfortable in. His poems go beyond merely expressing anger to explore how this emotion is accommodated in relationships with family and lovers. It seeks answers to questions about masculinity and identity, as in ‘Questions to My Mother’,

We keep so many secrets in our family. Why?

Why is sickness a secret?

The collection is necessarily a challenging one, but it brings the reader into the poet’s world in stages – life, culture, religion, family. As a collection of poetry, it reminds us that we are a depressingly long way from resolving issues of equality and oppression, and that there is no room for complacency.

Yomi Sode’s collection is peppered with references to British urban music – Grime, Hip-hop and other styles of which I’m ashamed to say I’m desperately ill-prepared to speak on, though their provenance is extensively documented in the Notes. Public Image Ltd’s John Lydon observed that ‘Anger is an energy’. Manorism is an extraordinary collection steeped in positive anger and purposeful energy. It is demanding to read yet impossible to look away from.

Andy Jackson

Leave a Reply