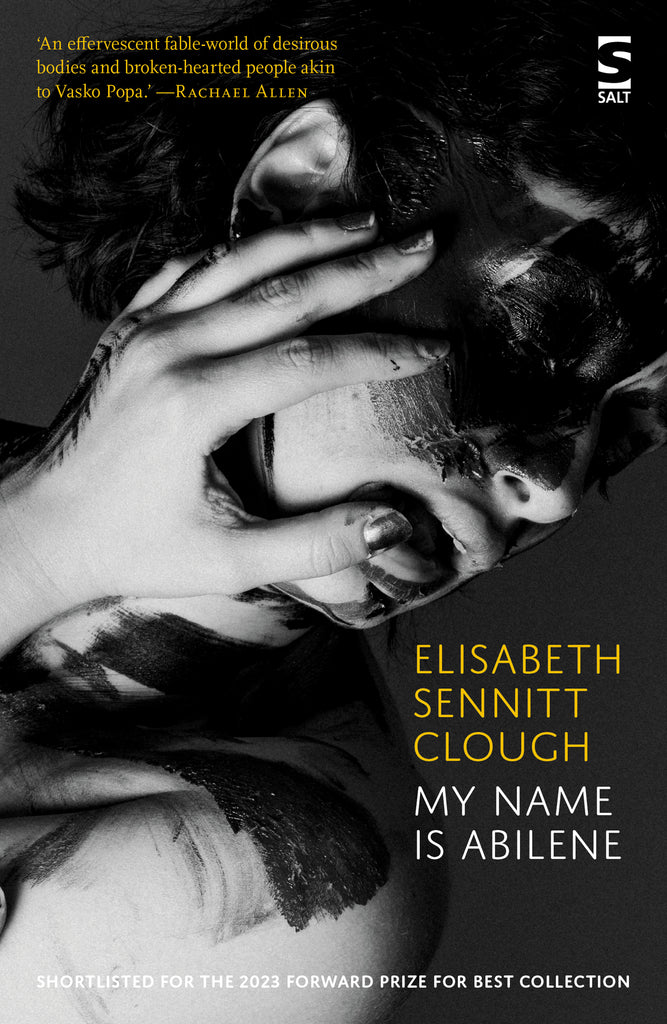

my name is abilene (Forward Prize for Best Collection 2023, Shortlisted)

Elisabeth Sennitt Clough

(Salt Publishing, 2023; pbk: £10.99)

What becomes of the broken-hearted? How did the shattering occur? Who wears the scars and for how long? Such is the sway of the power ballad for the titular abilene. Why is it abilene, and why is she already shorn of the normal confidence of an upper case opening letter? It’s not even her real name.

Rachael Allen describes a collection which ‘is a haunting’, whilst John Greening terms it ‘almost a verse novel’. I’m uncertain where the parameters lie, but in this Fenland Gothic tale, Elisabeth Sennit Clough (who is from that area) conveys the almost-trippy drift from the subconscious, ingrained with something painfully real. And all of it arrives with a level of formal poetic crafting which lifts this narrative into the extraordinary. For me, it is a verse novel, which in its telling, depths, and its sharply-employed devices, drives the relatively few words and white space of poetry to create a far bigger, more ambitious picture. Even the symbols which separate stanzas are chosen for their precise meaning. This is poetry on the page at its most intense. Equally, performed, my name is abilene must detonate.

what kind of woman kneels before such neglect?

(john calls abilene dramatic)

There’s the Fens’ inescapable flatness, and the protagonist’s resultant inability to find a figurative perspective, as everything reeks with the eely, unpunctuated darkness of unending soil and water. An often dangerous anthropomorphism broods through the flora, fauna and cultivation of the area. Understandably, John Clare is invoked, and with him shades of both nature and madness.

The collection opens by establishing the pattern of the maternal aspect of abilene’s intergenerational trauma, a history already too well-established to be readily slipped. Not that abilene is an easy victim caricature, unable to kick out or attempt to challenge her fate. Sennitt Clough’s characterisation is far too rounded for that. The not fitting-in locally, the learned cruelty, the superficial gentrification of the first section all rise towards the shockingly brilliant revelation of ‘When I Talk About Codes’. Without giving away the poem’s content, that titular capitalisation is the first use of uppercase type in the book. Typically, in this collection, the poem’s structure speaks as sharply as its words.

i believe in the sadness of rivers

sluiced off from their own mouths

[…]

how the ouse crawls to the ocean

a river on its knees

(my name is abilene)

Despite the naming of the section called ‘abilene’, john’s presence already looms:

in the pale-stone patio years of my life, john, I want to live with you in windmill gardens,

(abilene canvassing in windmill gardens)

and we know from the beginning, he’s not good news, undermining, gaslighting, and despite her attempts, of course as the poem title states, ‘nothing really severs’. That’s not to say she doesn’t give some excellent attempts, perhaps most strongly in ‘hanging out with rexie’, and in the bravely wonderful ‘abecedarian for the vagina’. Not many poems give so much in the title alone.

Structurally, the closing poem ‘Your Receipt’ (only the second poem employing upper case letters) mirrors what the listing of ‘the box of maternal recall’ does at the beginning. In that first section, already ominous with the title ‘before john’, after the unstoppable gallop of the unnamed first poem, it details what abilene’s mother handed her. Her daughter acknowledges:

none of this is your fault

That final receipt, sent to john, does hold him accountable.

Why abilene indeed? That far-off Texan town, with the complex and apt nature of the paradox named after it? Then again, there’s that power ballad.

The Hebrew name Abilene means ‘stream, meadow, grassy area’.

But when the poet fed her own full name into an online anagram maker, it offered ‘Abilene Fluorescent Nightclothes’. Sennitt Clough challenged herself to make a full poetry collection from that.

my name is abilene is the extraordinary, harrowing and brilliant outcome. Very much ‘a haunting’.

Beth McDonough

Leave a Reply