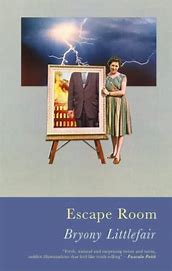

Escape Room

Bryony Littlefair

(Seren, 2022; pbk. £9.99)

Bryony Littlefair’s reflective collection Escape Room displays her resolve for happiness despite suffering from systemic pressures. She captures what it means to be human under capitalism and other oppressive structures, shaping, entangling memories and real events in her writing. This bending of words and perspectives is visible in ‘Tara Miller’

doesn’t have Facebook. I half think I made her up.

The poem then goes on to give us different versions of Tara. The intensely personal framing is crucial to the collection’s work, where Littlefair reveals the quirks and abnormalities of an unnatural world. The cruelty and abuse in ‘First job’ lays bare the workplace’s structure; simple requests are denied simply to reinforce control over her. Dehumanisation becomes especially eerie and stunted in ‘the other kitchen’, a poem that is an unrelenting wall of instructions, guidance, and reprimands all rolled into one. Her own role at work is vague, her colleagues weird and ritualistic, and the narrator feels trapped and isolated. That she must have her ‘own’ mug emphasises a false recognition of individuality, a token that ignores any real independence.

…oh it doesn’t matter i say anything is fine i say very easy-going and relaxed. no no no says mark, you must choose a mug, we all have our own one you see, it really is important that you choose a mug.

‘Lunch Room’ best emphasises the direct slander and contempt that permeates that space, the narrator’s ‘heart[…] deflating like the tired balloon it is’ as her attempts to enjoy life are punished. ‘Self-portrait at high-school graduation ceremony’ takes us back to a younger, youthful time with the narrator recalling the ‘adoring eyes’ of romantic interests while her ‘rallying’ club mates cheering her on. Even her parents, ‘divorced [but] amicable’ enforce a supportive positivity.

Yet, in this same poem she talks of Claudia, her ‘alcoholic mother and a borderline creepy dad’, who isn’t present for these joyous moments. Instead, the speaker has taken the morning coach out of this town, ‘burning up the road like a fuse’ in her escape. A suggestion emerges that Claudia’s difficult life resulted from the capitalistic modern-day systems in place, but that her escape for a life somewhere else turns out to be a false promise is evidenced by the narrator’s own experience of independent work.

‘Some therapists’, shows the result of this lie. A list of 20 different individuals, therapists, demonstrates her endless suffering. Some are helpful, some sad, some showing ‘no interest whatsoever[.]’ The narrator’s helplessness continues in the poem that follows, ‘Sertraline,’ named after the antidepressant.

Happiness could be bought

like helium in cans.

Yet, the collection shifts, evolves, recognising and taking new stances. ‘Dinner parties’, a poem divided into contrasting sections, mixing prose and poetry, is focussed on how recognition of what is real life has been brought low.

Love Island is an exploitative, heteronormative symptom of a racist, neoliberal and appearance-based society, but I just can’t stop watching it!

The narrator’s perspective changes, evolves, from her past suffering towards a better future. Embracing life, her resolve emerges in the collection’s final moments, and especially with the poem, ‘Legend has it’:

I’m still afraid but you’re here with me.

No one’s got a watch on and we’re here

to see the journey out. Death come get me.

Love come get me. We are alive and moving.

Taking real risks, embracing uncertainty, offer escape from a stunted, choked existence. Far from joining the capitalistic workforce and its lies of independence, the speaker turns to the excitement of living, creation, and experience. As such, freedom, is suggested by her quote in the penultimate poem, ‘The first time I read Frank O’Hara.’

And here I am,

the center of all beauty!

writing these poems!

Imagine!

James McLeish

Leave a Reply