Cane, Corn & Gully (FELIX DENNIS PRIZE FOR BEST FIRST COLLECTION, FORWARD PRIZE 2023, SHORTLISTED)

Safiya Kamaria Kinshasa

(Out-spoken Press, 2022); pbk, £11.99

Some books are intriguing, puzzling, challenging and yet also exhilarating. You can see patterns, strange, beautiful lines, powerful rhythms and urgent thematic preoccupations; yet each time you read, there is something so frustratingly strange about the work that the whole eludes you. But you are drawn in again and again. If a critic’s task is to ‘get it’, then I have failed miserably. I can’t put it in a box. But perhaps mastery is the least of what a critical encounter should be.

Safiya Kamaria Kinshasa’s debut collection of poetry starts with a quotation from Richard Ligon in 1657, ‘For what can poor people do, that are without Letters and Numbers, which is the soul of all business that is acted by Mortals, upon the Globe of this Word.’ Kinshasa asks, how does one speak outside of what is conventionally recognised as words? Might there be alternative languages? How might one recover from ‘the void of first-hand narratives from enslaved people (particularly women)’ something that will make sense to present lives? In ‘Preface: And if by Some Miracle’, positioned not at the start in the way of a normal preface, she writes of a transcendental dream-like encounter with past lives and stories, and of realising that through movement, enacted almost shamanistically, she is able to reach back. In her research as a poet in the colonial archive, ‘Sometimes when I danced, I inhaled the language of my ancestors’ captors, and they became mine.’ Through movement and ritual performance, connections are made imaginatively to different times,

the sisters shake day from their dresses,

lift & drop their shoulders like babies’ lungs.

swing themselves into tatty curtain shapes.

Those steps, enacted in the swaying of the body, echo across the ages—1742, 1975, 1936, 1997, 1925, 1544, 1992, 1694 (and so on)—

i became her when i was forced to let my old coast fall from my back Breadfruit & bottoms were caught like a fever past midnight i tried to undulate my destiny make note of this[…] (‘Choreography: She, My Nation’)

and on pages… with all of the fragments, white spaces and gaps that appear in the fallout of sentences and stanzas. This is a vision that makes a nonsense of time as essentially linear:

What women are these who cackle with their pelvises

thrusting thrusting thrusting

they will make totems with my hair. their nakedness.

(‘Excerpt from A True and Exact History of the Islands of Barbadoes’)

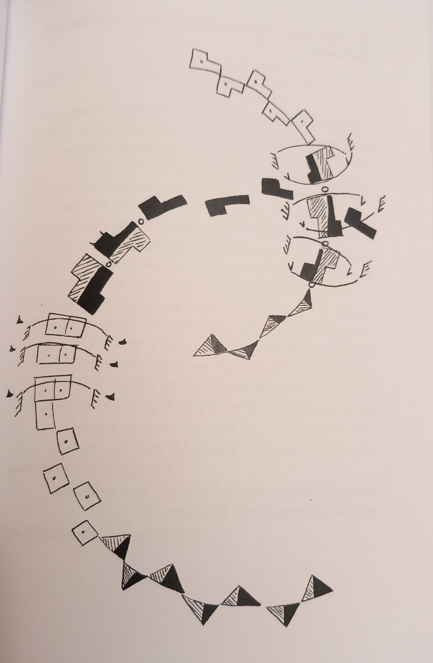

How to translate physical movement into ‘Letters and Numbers’? How to make poetry take on board the non-verbal? Kinshasa tries out different strategies – labanotation, a system of symbols developed for recording movement. These look like beautiful, strange hierographics for the uninitiated. Strategic gaps between words, punctuations where you least expect them, ampersands, italics and/or Derridean strike-throughs (to signal concepts under erasure) interrupt the ease with which one expects to read the line. In addition, there are incantatory lists, insistent rhythmic repetitions, the use of unglossed vernacular words, and the pistol shot of verbs emphasised using plosives to generate kinetic energy (for example, ‘we buckled our knees while drilling gills in our knickers’ in the poem ‘Testimonial…’). What these poems achieve is a relentless reaching for something outside the static page or sentence.

The body, or what the body is doing (or signifying) is prominent throughout, and a sly, knowing humour comes through the poem’s elaborate titles and their surprising metaphors or similes. While ‘you are strangling my butt like wet spinach’ (‘Cinderella/in Muhammed’s left fist’) made me smile, lyricism is never far away:

… i mean i made space

inside myself, the same way dusk sweeps

a gecko under its toenails[.]

(‘A Mother in Israel’)

As a collection that dares much, Cane, Corn & Gully is bewildering at times but Kinshasa is not unaware of the risks she takes:

I cannot tell you how to think or feel about my work…

but, if by some miracle you can acknowledge my

nation has always been speaking, then maybe they

can finally join in the discourse of their narratives. (‘Preface…’)

Ultimately, these are risks worth taking.

Gail Low

Leave a Reply