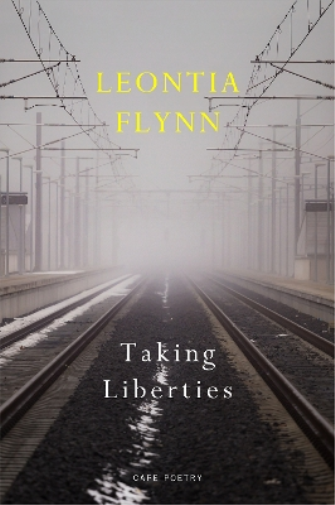

Taking Liberties

Leontia Flynn

(Cape Poetry, 2023); pbk, £12.

Is an image always a representation of something material that we see on the outside of us, or can it be something that we inhabit internally, providing us with a shape to express something otherwise that isn’t quite so easily realised? In The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard suggests that the poetic image is a confluence of the imaginative, the linguistic and material—the exterior interiorised and the interior exteriorised. Or as Richard Kearney observes in his introduction to The Poetics of Space, poiesis here is both matter and form: ‘we are made by material images that we “remake” in turn’, ‘setting verbs in motion and turning sensations into metaphors by inviting us to live figuratively.’

Reading Taking Liberties is just such a ‘live’, wordful and spatially-rich offering of rooms, houses, buildings, municipal pools, classrooms, cloisters and courtyards, public squares and art centres, motorway service stations, airport lounges and railway platforms, and more. These exterior landscapes, inhabited and interiorised, provide shape to a whole set of themes and scenarios played out within the space of a poem. ‘In the master bedrooms’ of ‘mortgage houses/in heritage/coordinated tones’, we are asked to wonder if the ‘Full Madame Bovary’ still plays out that drama of ‘ennui’ and discontent, and ‘unrealisable dreams’. In ‘It’s Solstice in the City’, the narrator scans her room wryly ‘for the remnants of/ My Gross Domestic Product.’ And in ‘All of the People’, the ways that we configure our dreams—live our modern lives—are critiqued gently when the narrator, clapping eyes on exhibits of evolutionary progress in the Natural History Museum, comes across how

Homo habilis strides, in pairs, from veldt.

The genome seeded, their wax eyes on the future

and ponders contemporary life suggested in popular catch phrases such, ‘I eat clean but train dirty’, ‘Let’s rank and yank’ and ‘When the looting starts, the shooting starts’. In ‘Dickinson in Amherst’, Bachelard is acknowledged explicitly; there images of a childhood ‘room-which-is-forever’ give a sense of a reaching inwards to render that more ethereal shape of intimacy and bonding, as the images reach backwards in actual memory:

A room, beautifully still, where the hairbrush or pitcher or the letter on the dresser is clarified in concentrated light. And nothing intrudes on the everyday arrangement to disturb its furious dreaming. The painted frame of a window suggests life’s going on elsewhere. A book is set down, a dress is draped over a chair.

Everyday objects populate Flynn’s poems but they seem to suggest a something else not always spelt out fully, as if the realism of the everyday is only the starting point for something beyond the materially seen. Her domestic interiors grounds the poetry but, more importantly, they also allow her to suggest a maternal hinterland, where ‘love’s magnetic dyad’ is embodied by and evoked through an assemblage of things that signify more than what they are.

‘In Classrooms and Science Labs’, ‘based partly on the testimony of Kimberly Rubio’ after the Uvalde school shooting in Texas’ is full of pathos as the mother of the murdered girl remembers the awful day when she ran, ‘flimsy sandals/held in my hands’, to the grounds of the school gates. As if in a film reel replayed, time flows between past of the killing, the present of its telling, the proleptic awareness of her daughter’s death in the moment of her running, and her present memory of that past. And finally, the future of a young life cut short tragically.

In the reel that keeps scrolling across my memory she turns her head and she smiles at us.

The poem’s changing of tenses from an imagined future, to a present telling, to the past tense of the mother’s remembered story, to the present tense of the grief, to the belated out-of-its-time trauma still to be reckoned with, is undertaken simply and quietly and through a temporal bead of images, tableaux even, and all the more heartbreaking for it.

Taking Liberties’ thoughtful exploration of time through a preoccupation with temporal flows and slips is evident in how one’s past lingers into the present, but also radiates into the future in poems such as ‘Nina Simone is singing’, where snatches of song stitches different times and places together. In the marvellous, ‘On Platforms and in Plate Glass Waiting Rooms’, time appears winged chariot like, in the form of a train moving through different places and landscapes ‘away from the moment’, an unspooling linguistic ribbon of names; ‘the rails stretch out// before them into the future’, ‘As a poem would carry the self far beyond the self’. If Bachelard writes, ‘the value of an image is measured by the extent of its imaginary radiance’, this lovely Bachelardian inspired collection of Flynn’s is quietly luminous.

Gail Low

Leave a Reply