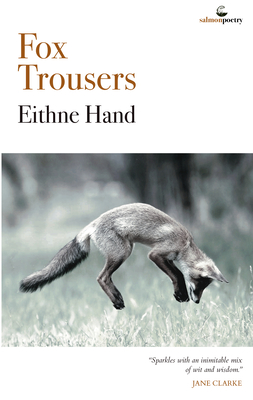

Fox Trousers

Eithne Hand

(Salmon Poetry, 2020); pbk: €12,00

Wherever your political inclinations, in the aftermath of the UK’s most recent election, it’s likely we can agree that we have all endured a certain amount of tired, repetitive debate. In poetry, probably, there are parallels in the regularly trundled out arguments polarising page and stage, discussions which could usefully be abandoned. Alas, like certain politicians, there’s still quite a lot of oxygen blowing around.

Salmon, perhaps Ireland’s foremost poetry publisher, is not particularly renowned for championing what might be pigeon-holed as ‘spoken word’. The greatly missed Jim Stewart would have been quick to remind anyone that no poem is truly finished until it’s performed, and he was absolutely clear on where the Ancient Greeks stood on that point. Yes, we’ve all heard someone, seismic at a slam, whose work really didn’t quite translate into print. Equally, who hasn’t read and loved someone’s work only to find them desperate to escape the podium give a cringe-inducing reading. Most poets, happily, will jump around somewhere between these stones. We have much to learn from one another.

[H]er story judged to be entirely fabulous

(‘The End of St. Barbara’)

Fox Trousers fires out a series of poems, gutsy in narratives and exuberantly upended memories, that certainly earning their place on the page whatever their leanings towards the stage. By all means, pick them over, parse, re-read and re-check them; they will yield more than they did on that initial reading. And surely that’s a mark of why any collection deserves be committed to print. However, it will come as no real surprise to read Hand’s biography (after the poems) and learn of her background in broadcasting and theatre. These poems are a cracking and accessible read, and if the poet ever offers a performance anywhere I can reach, I’ll be the first to book a ticket.

Perhaps there’s a slight delighting in the often punching qualities of those last lines, as in ‘blow-up doll’ sending off ‘At Sadler’s Wells Stage Door, London’, which many might suggest will appeal more on stage than on paper. However, there’s something in the poet’s humour which works hard and subversively and deserves respect. Particularly in that divided island, we’ve seen some very creatively inspired uses of comedy and absurdity, finding ways to sneak in the almost unsayable, and be received by listeners who might otherwise struggle to engage. That’s something certain traditionalists need to consider. Think of Patrick Kielty’s selfless courage. Think of Lisa McGee’s bittersweet alloy in Derry Girls. Why can’t poetry go there too? Are we really too stuffy for that? Master verse craftsman Don Paterson has plenty to say about how we dissect poems, and he’s unafraid of a bit of ludic joy, well-laced with earthiness when the occasion calls.

‘Border Bus, 1979’ crosses The Troubles with Apartheid. Yes, perhaps Eithne Hand does have a love of the double entendre, but there are various poems slipped which, partly as a result, undermine expectations, and there is so much sharp observation, recalling, for example, that ‘slouch of schoolkids’ (‘Barnaby Park 7.55am’) that hits home, harder than the now softened-up reader might expect. The poet has a way of unwinding certain collective memories, perhaps in the school gym hall or via the evocations of litanies, and she has an unerring capacity to chaperone us to ‘a summer/ when being alive seemed unnecessary.’

This is Hand’s first collection. It’s even possible it might be her last, not because she hasn’t done it well. She has, as her poetry periodical track record also tells, been spending ‘her time between Greystones and Ballinafad, Co Sligo’ apparently. Looking at her cross-genre list of achievements, I’m amazed she has any time. Her poetry, and our reading of it, is so much the richer for that mixed cultural experience.

Beth McDonough

Leave a Reply