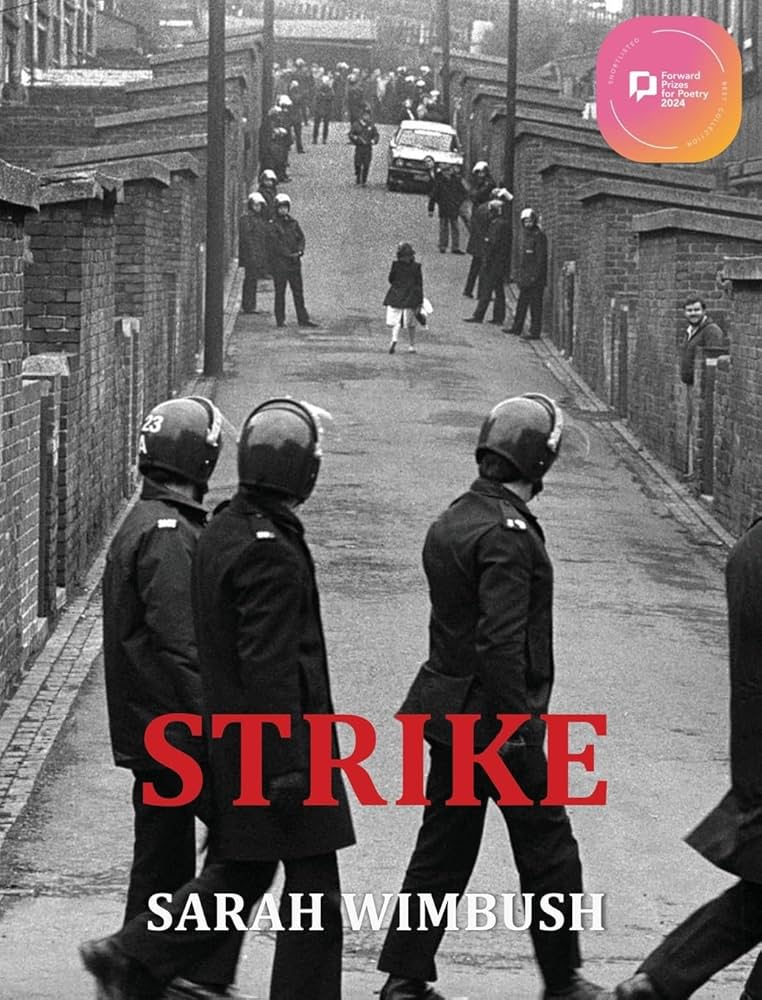

Strike (Shortlisted, Forward Poetry Prize Best Collection)

Sarah Wimbush

(Stairwell Books, 2024); pbk, £15.00

300 million years of compression

dripping through their hands.

(‘Boy Riddlers’)

Trade union activists reading Sarah Wimbush’s Strike will recognise those turbulent meetings, the passions, pains, waved placards, and they will know both the lasting comradeship and the perpetual divisions germinated during prolonged strife. They will be pulled quickly into the narratives and insistent rhythms which propel the collection’s relentless march. Arguably, no modern industrial dispute in the UK has ever been as harrowing or as devastating as the Miners’ Strike of 1984-85. A reality which significantly outlasted those dates.

Outwardly, Strike‘s formatting and consequent shape is unusual for a poetry collection. Indeed, from the outset, the book offers a feeling of grasped papers; the text’s chronological arrangement developing as each double spread layout offers a poem on the left hand page, directly addressing and interrogating the photograph on the right. It’s an effective device, positioning the poem first, leading the eye to use that to unpack the image, and then return. Be it the horror and courage of the pickets, the posters, or an NUM membership card (‘the size of a bus pass/ and the Magna Carta’), this makes for a powerful, and simultaneously haunting, progression. The typesetting, the titular capitalisation (notably usefully dropped in three poems) and the typewriter-like font, all contribute to the eighties in history build-up of news.

Wimbush charts the symbiotic relationship between mining communities and that fearsome, personified geology, taking poetic fallacy to an often extreme edge Framing that ‘muzzle of a mountain’, both as mouth and readied firearm, already the reader is ‘unpicking the scab’. Opposite that particular poem (‘Kick-off’), there’s a picture of police and pickets playing football. However, with ‘Subbuteo on the hotfoot’, and references to chess, demonstrably, the miners are already being played. In a strong seam of ludic, yet tensely sinister, wordplay the poems shape and foreshadow what is to come. Her use of repetition, rhythm and internal rhyme are propulsive. Marches, pickets and protests are conjured, and at the time of return to work, that hard-working rhythm alone tells of metal chipping at the coalface.

Some of the remembered major players like Thatcher, Kinnock and Scargill are portrayed deftly. Had I forgotten how that last ‘raises his iambic voice, that finger’, I cannot now. If I had almost forgotten Ian MacGregor, this collection will ensure I won’t again. In the ‘brass band of musicality’ (‘Stop’) these poems re-awaken the times for those of us who lived through them, and can recollect when ‘Inky corridors began to infect conservatories’ (Scargill). But these are also lines for the peers of ‘People who are children of the people who lived/ and died on the blunt end of a pick’ (‘People who support the Miners’). The litany of lost colliery names stands starkly before the poems.

Strike is not any easy, one-sided Howson-like glorification. Carefully, the poet examines conduct which was not invariably heroic; her unflinching words are nuanced and therefore brave. There are also celebrations of the wider support like that made famous in the filmPride, as Wimbush’s lines pick up Bronski Beat’s brilliance. The role of women is justly lauded, as

they stand before their husbands

instead of one step behind[…]

and pull their daughters forward

and stand them in the light.

(‘Women’s Support Group’)

Even in 2024, these materials could detonate dangerously. Unfettered fury and injustice don’t always make great poetry. And the poet’s own family history gives her more right than most to pull that pin. Her achievement is remarkable. Just as Strike will call to both those who lived it and those born later, Sarah Wimbush has achieved the extraordinary, creating a collection, harnessed tightly by formal poetic devices, which opens doors to those who might not read contemporary poetry. It will also be read and re-read by those who do.

Not so many collections manage that.

Beth McDonough

Leave a Reply