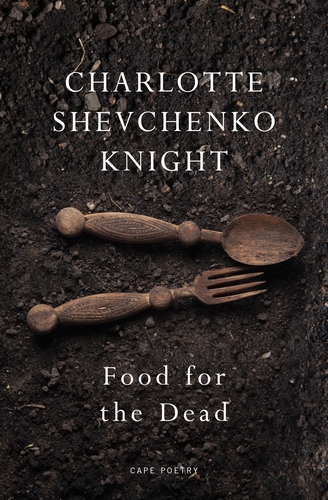

Food for the Dead (Shortlisted, Forward Prizes for Best First Collection)

Charlotte Shevchenko Knight

(Jonathan Cape, 2024); pbk, £13,

Food for the Dead by Charlotte Shevchenko Knight is a hauntingly evocative poetry collection that weaves together Ukrainian history, personal memory, and the deep scars of generational trauma. At the heart of the collection is a powerful timeline of interconnected poems, moving backwards from Kyiv in 2021 to Donetsk in 1929, creating a poignant thread of shared suffering and survival across the decades. Through this reverse chronology, Knight explores how events like the Holodomor, World War II, and the Chornobyl disaster remain embedded in the collective Ukrainian consciousness.

Knight’s long poem that stretches from Kyiv to Donetsk intertwines images of food—beetroot, tomatoes, and seeds—with visceral metaphors of blood and hunger, symbolizing both sustenance and loss. While ostensibly about food, the imagery emphasises how the tragedies of one generation echo in the bones of the next, highlighting a painful legacy that unites Ukrainians across time and space. Central to the collection is the role of Ukrainian women, particularly the babusi (grandmothers), who act as both survivors and preservers of culture and memory. The poems evoke their battle to simply ‘be’, crawling, gathering and sometimes laughing but ultimately surviving while their men are ‘nowhere to be seen/presumed fishing/or dead’ (‘Dnipro 1933’).

Her writing style is marked by its lyrical, fragmented quality, with an emphasis on the sensory and the visceral. Her language is raw yet delicate, creating an intimate and almost tactile experience for readers as she navigates complex themes like famine, war, and survival. She interweaves themes of food throughout her work, where the consumption of food becomes a proxy for the consumption of lives in the suffering she depicts.

Her ability to balance personal and collective narratives is another hallmark of her style. She often shifts between intimate, familial moments and broader historical reflections, seamlessly blending the individual with the generational. This creates a sense of continuity, where the traumas of the past are passed down and still felt in the present, adding emotional depth and resonance to her work.

The experience of women as survivors pervades the work, where their survivor guilt is intermingled with their guilt over food consumption. For example, ‘mama steels the government-granted baby food for her sister….meat glimmering with its own sweat/as though guilty of feeding/the wrong child’ (‘donesk 1984’). Food imagery, and at times starvation and desperate hunger is interspersed throughout the poem. The hunger is the ‘disaster’ they fear, at times more than death itself. For example, the poem describes the aftermath of an attack where the only remaining sustenance is the dirt under the fingers of a dead man. This is contrasted with the extreme colour of ‘neon strawberries’ (‘donesk 1986’), watermelons and drying clementines.

From the perspective of the western reader, sitting in a comfortable and safe home in the UK, little moments of revelation and connection emphasise that these experiences could so easily have been shared – the fisher price phone (‘donesk 1999’) – at the same time as portraying extreme differences – the family cow is shot by soldiers (‘donesk 1932’).

This journey not only connects historical events but also emphasises the cyclical nature of oppression and survival, and the indomitable spirit of Ukrainian women. The poem offers a tapestry of inter-generational experience connected by food and sensory awareness, revealing how the past continually informs the present. Knight’s collection is both a lament for a nation and a tribute to its endurance and is therefore a necessary contribution to contemporary poetry, offering an elegant counterpoint to historical and modern oppressions.

Susan Kinnear

Leave a Reply