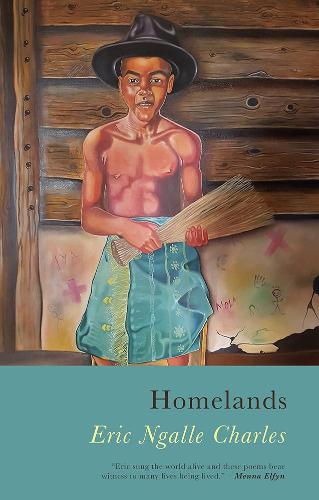

Homelands

Eric Ngalle Charles

(Seren, 2022); pbk, £9.99

Eric Ngalle Charles’ work covers his life and experiences as an individual with an identity that has been pushed, and stretched over and around the world. As the blurb describes, his life is one of displacement and trafficking, being taken from his home in Cameroon to Russia, before finally settling in Wales, from where he now describes his story.

As noted in the collections title, Charles’s writing draws from his origins in Cameroon. Utilising words, phrases, figures, and imagery amidst English adds a strange quality to his poems , a peek into different cultures. His explanatory footnotes add clarity, creating a contrast and a supplement to his poetry, allowing the reader to glimpse both facts and feelings, and experiences. ‘If Heaven Is Her Father’s Land, Her Father Can Keep It’ is one piece that embodies his unique experiences, appearing as both a story and a prayer:

Yes,

She wants to go where Evasrikuke sings:

where she can grow Mbasri side by side,

where Ezruli sucks nectar with bees as companions,

where water flows from Hvako through rocks

feeding the grass fields of Weli,

and all the dwellers along Namongeh.

The collection’s non-linearity too embodies a preoccupation with different moments and memories, continually looking backwards and digesting his life through writing. Poems such as ‘Great Grand Aunt Vera’ offer this introspection; he recalls a woman who too is caught in her own memories.

Her wrinkes like land markings, she speaks of permanent

longing, her neck moves slowly, scanning the horizon.

The speaker connects to this woman, with the poem itself being both a memory and in memory of her. One moment in the long journey that Charles undertook, the bench, ‘the Lavuchka’ where she sat, becomes an image of his time in Russia at a point where many lives passed but where, to him, one forever sits eternally.

No wailings, no choir groups singing, just

a Russian bench which reminded me

every evening at 9:30 that Teta Verya

was dead.

Movement through space and culture is paramount to his writing, and like his Cameroonian phrases, Russian and French also emerge, detailing his international existence. Yet, with the focus on his life being taken away from home, family is central.

Both ‘For Namondo, My Wife’ and ‘Small Black Box’ detail his relationships with his wife and sister respectively, but their warmth is broken upon the poem ‘Inheritance (1988)’, detailing his anger at his aunt, the one responsible for his abduction. In this poem, amongst others, pain is laid bare, but growth and change borne of his circumstances are also evident:

I promised

never to speak or write of her, ‘till she withers

and winter’s hard winds blow her skeleton

to pieces and her coffin spits her bones.

Indeed, this betrayal feeds into the spirituality that Charles invokes. ‘When They Came’ describes an invasion into the village, an attack on a woman, where he calls out Ndondondume, a figure noted earlier as a devil luring people to their doom. That the real and the spiritual blend together is reinforced by Charles’ variance of tone and structure in his pieces, as with ‘Cymru’, a disjointed piece which defies reality, but follows the collection’s tone of displacement and violence:

In Abertawe

fingers point in direction of her birth, her tongue

cut

she carries her head in a bowl, sharp blade dig

harvesting her memory.

In the uncertainties of exile,

she once

danced like a jester.

It’s fitting, that the eponymous poem ‘Homeland’ embodies the sentiment that Charles endeavours to share:

We cry for you,

here in our diaspora,

your children wandering barefoot,

are treated like knaves

with no names[.]

The vivid, violent displacement that Charles describes in ‘Homelands’ is given a new twist as he quotes Ifor ap Glyn, the National Poet of Wales, lines which draws us back to his present life and new home there, but reflecting also on his situation, and all the diaspora he writes about: “A child given Sellotape to fix their broken biscuits”.

James McLeish

Leave a Reply