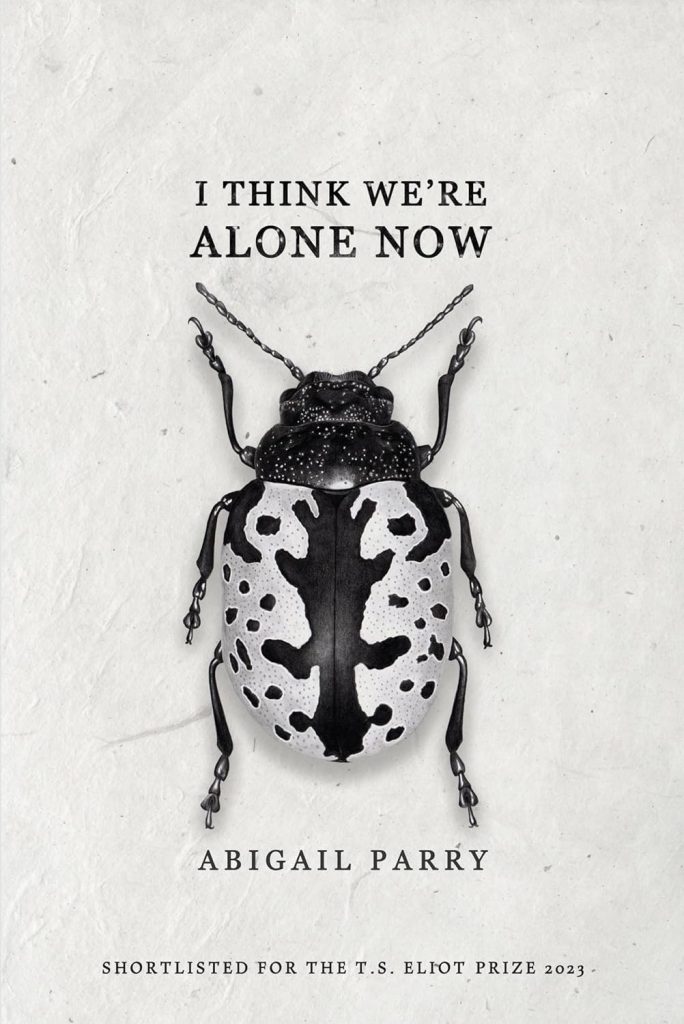

I Think We’re Alone Now (Shortlisted, TS Eliot Prize 2023)

Abigail Parry

(Bloodaxe, 2023; pbk, £12)

And this has always been the case,

but no one thought to tell me.

(‘some remarks on the General

Theory of Relativity’)

A title like ‘The brain of the rat in stereotaxic space’ makes a bold opening gambit. The reviewer is aware the poet has had a past career in toymaking and is soon alert to the intricate care inherent in the constructing of these poems; a planning, an almost archaeologically labelled or museum-catalogued craft. These impressively, formally varied poems are precision-assembled, and there is something in each—be they sonnets, sets of sestets, runes, guitar chords, or even a tightly metrical poem where only one of its 33 lines and title does not end on the name ‘Rosemarie’— which tells of meticulous planning, exacting execution and a mesmerising, unrelentingly creative mind. Foolishly, however the reviewer has failed to read the collection’s Thom Gunn epigram in time:

For if the watcher of the watcher shown

There in the distant glass, should be watched too,

Who can be master, free of others; who

can look around and say he is alone?

If poet Abigail Parry’s challenge was to examine intimacy, does she do this, or does she spin the tables? You might think, with the subject of her second poem (‘Speculum’) being a smear test, that she’s going where you could reasonably expect on that theme. But with her ludic joy, and some Sharon Olds-equalling double-entendres, shot through with Lewis Carroll, Hamlet and more than a dash of ‘First Corinthians’, the mirror isn’t playing that straight.

The reader may pick apart marvellous devices, underscoring certain narrative propulsions, and likely recognise the grim waitress, who in ‘the brutal/certainty of being seventeen’ finishes with that relish of glorious zeugma:

She’ll pull this city to the ground before

she’ll take your plate, let alone your pity.

(‘In the dream of the cold restaurant’)

Possibly you begin to feel you know where you’re going with this poet; but there are more aces up her sleeve, tucked behind a whole suit from the Minor Arcana. Also, there’s a lurking irony, taking an excellent twist on the didactic nature of what a colonising language might do to learners. The poet’s next move could be filmic, or have a theatrical, even Shakespearean aspect:

Roll over, feel the slow

poison of the sentence sinking in

(‘Romeo and Juliet’)

and perhaps the reader might be lulled into the shanty-like repetitions of ‘Lore’ and find fun in that subversive use of rules in ‘A beetle in a box’. Who better too than black and white artist Escher to be referenced in these perplexing illusions?

But Sir, I know an initiate when I see one

(‘The Fly-Dressers’ Guide’)

Hopefully, by now the reader has been reading the endnotes, because whilst some readers may be familiar with the game of Giallo, this reader certainly wasn’t, and in fairness, not so many might have seen that particular angel mural in a London pub. In the intermingling of epigrams, epigraphs, differently mapped notes, and quotations from anything from classical literature to a pop song, the reader will certainly recognise the need to manoeuvre around a formidable strategist. And just when you draw up your chair and furrow your brow:

But listen, pal, I’ll take

whatever gets me through today,

so unless you’ve got diazepam, it’s runes.

(‘Rune poem for a funeral’)

That’s a freakishly cheeky and familiar intervention, when you least expected it, and a quite brilliant take-down of funeral rituals. The end of the game is in sight, of course, and by now you shouldn’t be surprised that Abigail Parry has decided to close on openings.

This reviewer knows she has been played. Spectacularly. And when was it ever a contest between the reader and the poet? Sometimes it’s good not to know so very much, and to revel in the joyous certainty that you’ll want to come back again, and again and again.

Beth McDonough

Leave a Reply