‘where and who we are’: two pamphlets

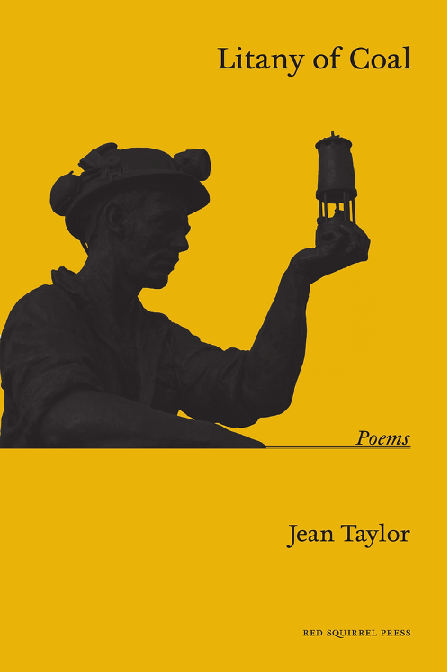

Litany of Coal

Jean Taylor

(Red Squirrel Press, 2023; pbk, £7)

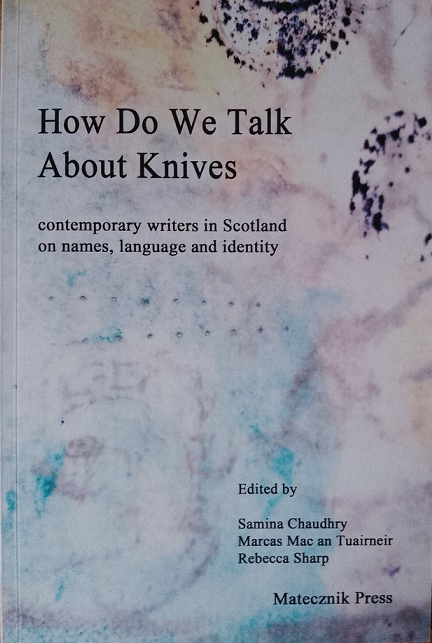

How Do We Talk About Knives

Samina Chaudhry, Marcas Mac an Tuairneir & Rebecca Sharp eds

(Matecznik Press, 2023; pbk, £10)

[…] who would I have been?

You need more than the alphabet to make a name.

(‘The Things I Carried to a Foreign Sky’)

Vietnamese-born writer Ngan Nguyen’s lines (from How Do We Talk About Knives) speaks to some of the underlying and important questions about identity and acceptance explored in these two very different short collections. Published by two vibrant independent Scottish publishers, the quality of the content and the uncompromising editorial and aesthetic standards shine a real beam of light in these difficult times for print collections, times that are in truth never easy anyway for small poetry presses. Bravo to both Red Squirrel and Matecznik for bucking the problematic trend.

Dealing first with Jean Taylor’s tightly-made family history; if you think you are familiar with the literature associated with Scottish pits, prepare yourself to be surprised. The poet’s lines are hewn not only from the Lothian coal seams but from generations of her family’s involvement with mining, both here and in Nigeria. The cover illustration, which at first glance appears to be a silhouetted portrait of a miner, on closer inspection reveals far much more detail in the darkness, and that in itself seems a fitting introductory statement. Now, look beyond those beautifully black endpapers.

We have the rhythmic, ringing and kindly strength of the blacksmith grandfather (‘Blacksmith’), with its series of compounded words. This is a poem which is in so many ways ‘a hinge for the colliery gate’, in both its positioning in the sequence, and its figurative ability to control more than one direction. The poet takes us into the tight strictures and shibboleths of the mining community where ‘Freits ruled their lives’, ‘freits’ being ‘superstitious beliefs or customs’ (‘Married In’), and that poem, paired with ‘Not from Edinburgh’ conveys that sense of being the eternal incomer, ‘through years of never settling’. Indeed, that unwelcoming truth of very closed societies strikes its uneasy chord with matters also considered in How Do We Talk About Knives.

A poem like ‘Portrait of My Father in Old Age’ is in itself seismic, mining the depths of rich personal histories, and what is left to sift as

Now he digs through

the dead nerves of his brain

seeks out dopamine[.]

There is of course the hard irony, sharply carved, of the relentless dangers and damning cruelties of the coal industry and how

I expect they chose canaries

because they were smaller

than sitting ducks[.]

The filth, the class inequalities, the environmental dangers, some of them ‘ready to suck children’ (‘Mossmorran’) are here, but it is in ‘The Plaque’ that a brave uneasiness with family pasts is first raised. And how courageously the poet holds her once-believed ‘guilt-free lineage’ to account in ‘In the Family’. There is, I think, a wider aspect of this painful realisation which needs to be shared in a Scotland too often strangely amnesiac in the examination of its own colonial past.

Painful, yes, but also hopeful; this collection, written with ‘the sharpness of anthracite’ (‘In His Shoes’), ultimately readies us to understand and accept what is ‘scooped from the rich seams/ that lie untroubled now/beneath the Firth (‘Spring Tide’). Litany of Coal contains a remarkable span in twenty poems.

How Do We Talk About Knives is subtitled ‘contemporary writers in Scotland on names, language and identity’. Before embarking on any of the poetry, it’s certainly worth giving full attention to the three editors’ excellent introductions, and also to the Foreword written by Kirsty McHugh and Ian Scott (curators, National Library of Scotland), followed by former Stanza Director Anna Crowe’s ‘Contemplation’. Anthologies, by their sometimes disparate nature, can be awkward to capture in a review. This one, however, makes its case powerfully from the outset, and is then able to allow a remarkable range of writers to tackle the subject from very differing perspectives.

Editor Rebecca Sharp’s own surname prompted the title, and her superb titular poem asks us to consider those ‘shimmering dualities’ referenced in her opening words.

What, after all, are names? The patronymic looms large, of course, not only in English, but in Gaelic. Fellow editor Marcas Mac an Tuairneir invites us to look at Gaelic traditions, so seemingly familiar to all in that ‘Mac’, but also he enquires about what has been handed down via occupations, religious practices and, of course, nicknaming (how many really know about those twisted-mouth Campbells and bent-nosed Camerons?). Mac an Tuairneir is himself a new Scot, a Gaelic learner from Yorkshire , and his discussion on the ‘Gaelic Baptism’ is moving indeed.

What of the New Scots who have arrived here from more distant parts? Samina Chaudhry, editor of Scottish PEN Writers-in-Exile, is wise in her examination of how ‘we navigate the push and pull between self-expression and what a society implicitly enforces in the guise of assimilation and integration’.

Then, there are the pen names, which may allow writers ‘to fit in or stand out’, or ‘to create a distinctive authorial brand’. In truth, there is already meat for several anthologies before the poems have cast a single line.

The variety is extraordinary, and gives a real flavour of what it is to name yourself anywhere in Scotland in 2023. David Bleiman’s surname travels from a Lithuanian shtetl, with shades of Yiddish and Hebrew, closing on a rather a glorious nom de plume/nom de plomb pun (‘Plumb Lines’). Whereas, Gillebride MacMillan’s list poem of questions asks

A gealtair’ mi nach d’ atharraich m’ ainm air ais gum dhualchas fhìnAm I coward not changing my name back to own heritage[.]

(‘Ciod e m’ ainm?/ What’s in a name?’)

Certainly, that’s a vexed question for several contributors, and there’s a strong sense that some of the female Gaelic poets, notably Cairistìona Nic Dhòmhnaill Stone, are making brave moves to challenge the patronymic, rather as their Irish counterparents are already able to do without recourse to deed polls and extensive legal vexations. ‘Cò do Dhaoine/Who Are Your People?’ Ask, how much does your name carry from your foremothers as well as your forefathers?

Then we have the surprise of Italian-named ‘Malgrati’, Paul Malgrati’s joy of an encompassing macaronic, kicking off in an Italian still strongly shaded by Latin, nipping through French, English, and finishing in Scots. Readers would do well to seek out the freshness of his Franco-Scots poetry…a unique voice indeed.

I opened this review with a Vietnamese-born poet’s words, but there is also the surging Shona riding through Tawona Sithole’s extraordinary ‘praise praise poetry’:

long awaited rain is pronounced by words

tonhodzai pasi changamire

long awaited rain is announced by birds

kwoovira kwoovira

inenge yaa kuti tsvo tsvo tsvo tsvo

wild ways of witnessing

that leads seamlessly to Stirling Makar Laura Fyfe’s ‘peelywiwally, skinnibelinkie/nymph (‘Termite Quine’) and Christie Williamson’s Shetlandic assertion that he ‘wis up da stairs/wi a nem/I gied tae him/an annsir tae’ (‘Annsir’).

Names of choice, challenge, change, convenience and far more. It certainly feels as if How Do We Talk About Knives has lit a certain touch paper, and it would be wonderful to hear and consider more. The editors have prepared various readings and talks on their themes to launch and promote the book, countrywide.

How Do We Talk About Knives is an entirely different kind of collection from Litany of Coal, and yet there is a substrata in both which questions where and who we are, and if we are really what we first think, or find ourselves presenting to the world beyond. We need to keep asking these questions.

Beth McDonough (Beth Campbell/Beth Craig)

Leave a Reply