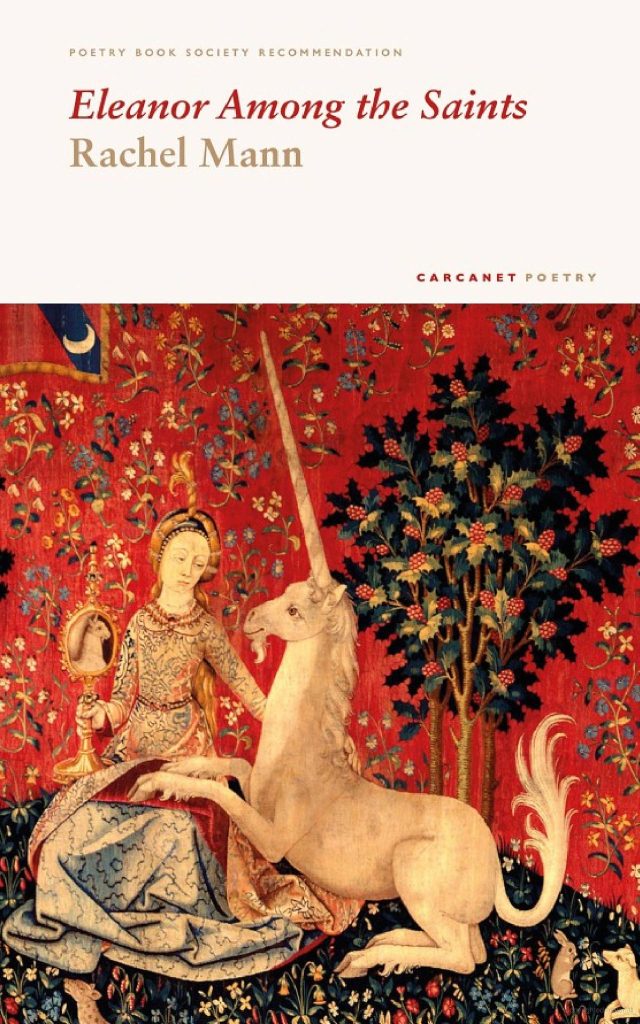

Eleanor Among the Saints

Rachel Mann

(Carcanet 2024); £11.99

Rachel Mann’s second poetry collection, Eleanor Among the Saints, begins in the seamstress’s workshop with the poem ‘Embroidering a Priest’.

He I we shall be complete, he will forget (we all do)

The mysteries of his making, a birth. He will be

All flounce, a skin, layers of bride mesh,

He shall know folds.

What is happening here in this poem of neat four-line stanzas spattered with Latin phrases? Is this blasphemy or worship? Is this irreverence or supplication? These questions are no more easily answered when you know that Rachel Mann is an ordained priest and archdeacon of Salford and Bolton, or that this poetry collection takes as its protagonist a trans woman sex worker and seamstress who was arrested while working in 1394. That last line grabs attention. An ambiguous declarative? Joyful or threatening? These are strange words worth paying attention to lest they slip under the page and change before the reader can grasp their significance.

Religious sumptuary runs through this collection as do bodily fluids. Swearwords are slipped between folds of incantation and its grammar is, at its core, queer. The last stanza of the first poem of the collection, ‘Embroidering a Priest’, sets out its stall.

This is bodily love poetry reminiscent of Allen Ginsberg at his most tender and gory. But where Ginsberg’s angels were psychedelic, Mann’s are troubled, made strange and complex, brought down to earth and often bleeding along with the rest of us ‘His burnt-out wing, the stumps of near divine’.

The collection is divided into three parts, the first, ‘Eleanor Among the Saints’ imagines Eleanor Ryker in conversation with three saints, all roughly contemporary to her: Catherine of Sienna, Katherine of Alexandria (famous namesake of the Catherine Wheel) and Saint Perpetua, ‘an early martyr of the church who reputedly changed sex from female to male at the moment of her death in the Roman Arena.’

The second part, ‘Praise’, is the most liturgical, a priest’s grappling with the shape of her work during lockdown, a daughter holding vigil at her father’s deathbed. The effort towards praise during such dark times is deeply moving. Poetry with such overt religious feeling could risk alienating readers who do not share the poet’s particular beliefs, but these words cut through to something elementally human in their reaching towards faith and gratitude in such painful times. ‘The Lord be with you, and my mask slips from nose’… ‘I can hear song above technology (headphones, unmute, cue in, 3,2,1).’

‘A Charm to Change Sex’ is the final part, speaking most directly to Mann’s experience of her own body; its relationship to earth, life, her God. ‘A Charm to Change Sex (3)’, and the two preceding poems are short, single-stanza poems written in the two-columned form of an Anglo-Saxon metrical charm:

Nail, nail a tree splits, sap drips, wood is meat And meat is iron worthy of praise, iron-meat[.]

It’s in this section we find the poem ‘#TDOR’, a heartbreaking, weary poem written in the tone of a breathless string of polite and well-meaning emails requesting the poet attend events to remember trans people killed in the past year. Its impact should be experienced in full, rather than in a short quote. It is a powerful view into the emotional toll and relentless word-work needed to be a trans person in the public eye.

Rowan Williams is quoted in praise of Eleanor Among the Saints on its back cover, with a comment elegantly appraising Mann’s work, and this collection in particular, as written with ‘exhilarating verbal energy and emotional subtlety, a poetry that is solid and fluid at the same time, as bodies are.’ This is the sense one is left with after reading or hearing Mann’s poems: a sense of words transforming bodies, of bodies transforming words.

Ellie Julings

Leave a Reply