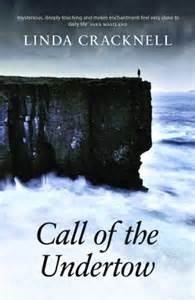

Call of the Undertow

There is something compelling about the recent spate of texts that employ cartography or walking as a trope for addressing how we inhabit our environments: finding the rhythms of place and space, marking your body in relation not only to the world around you but also to physical, textual and figural ‘others’ that have traversed the same ground. Linda Cracknell’s “footbook” Doubling Back, recently reviewed on DURA, and her debut novel Call of the Undertow, published late last year, attest to such preoccupations.

There is something compelling about the recent spate of texts that employ cartography or walking as a trope for addressing how we inhabit our environments: finding the rhythms of place and space, marking your body in relation not only to the world around you but also to physical, textual and figural ‘others’ that have traversed the same ground. Linda Cracknell’s “footbook” Doubling Back, recently reviewed on DURA, and her debut novel Call of the Undertow, published late last year, attest to such preoccupations.

Call of the Undertow concerns a middle-aged woman who deliberately flees from a cosy, middle-class and suburban Oxford to the wilds of Caithness in North Eastern Scotland, in an attempt to escape a past trauma that still, of course, haunts her. Maggie, a cartographer, is reserved and defensive, and has trouble forming friends among the villagers she meets who mostly treat her as a passing tourist or incomer. Drawn to a young nine year old boy, Trothan, who is equally set apart, the pair bond over the making of maps. Literally a wild child because of his habit of roaming the countryside alone, shunning human company, Trothan as a character is also associated with the selkies; seal-like sea-creatures who might take on human form for a time before returning to their watery home. The lesson Maggie learns from her charge is that place is not simply what you see but also concerns stories, affective connections and imaginative relations. Unlike Maggie’s professional work, which is based on empirical evidence and used for information retrieval, Trothan’s map puts more in, charting a kinship which takes in the historical, the aesthetic, the fabular and the mythic. His map making is “highly detailed, figurative, but also conveying a real geography”, connecting the land and the depths of the seabed; “it seemed to take the artistic merit of early maps, the later passion for accurate geography, but then add a further layer of story and subjective interpretation of the landscape.” Maggie’s troubled bonding with Trothan allows the reader a delayed glimpse into her own difficult past and enables Cracknell to plot a redemptive healing and a final settlement.

Reading Call is like savouring slow food; however, the wider society of Quarrytown village, or even Scotland, is not the novel’s preoccupation. Instead, the novel offers Maggie’s present troubled psyche and her commitment to a boy who ultimately remains unknowable to her (or even to his own family); details of her past life are deliberately withheld from the reader till late in the novel and only sketched fleetingly. The evocation of Scotland’s sublime landscape (in the Edmund Burkean sense) is Cracknell’s main focus and the locus of its intensity; in this, Trothan’s liminality – human and animal/mythic – is key. The best sections of the novel hint at a strangeness that is beyond human ken, an unhomeliness that is neither a full-blown gothic supernatural nor an oddity that can be explained away; this ambivalence and its potential for menace (or later melancholia) begins with disquieting incursions into Maggie’s private garden in the novel’s opening pages.

Cracknell’s novel works best as a mood piece. The more homely narrative of Maggie’s story doesn’t always sit easily with the bigger canvas of the literary sublime nor with the redemption suggested by the congruence of the natural and the human at the novel’s close; the conclusion seems seems a tad “pat”. Other issues taken up and then dropped – how communities draw lines between insiders and outsiders, what exactly Trothan signifies for Maggie, the wider politics and dynamics of belonging – suggest at times a book that hasn’t really settled in itself and having opened a Pandora’s box of themes hasn’t quite managed to put them all back. Despite these reservations, Call of the Undertow sustains its marvellous depth of feeling. The cartographic and/or perambulating trope, and the sublime evoked that is in turns beautiful and terrifying, are very finely wrought. Call’s engagement with hearts as well as minds responds to the question posed poignantly in Kei Miller’s The Cartographer Tries to Map a Way to Zion; “how does one map a place that is not quite a place?”

Gail Low

Click HERE to see Linda Cracknell and Jean Rafferty in conversation with Kirsty Gunn at the Writers Read series at the University of Dundee.

Leave a Reply