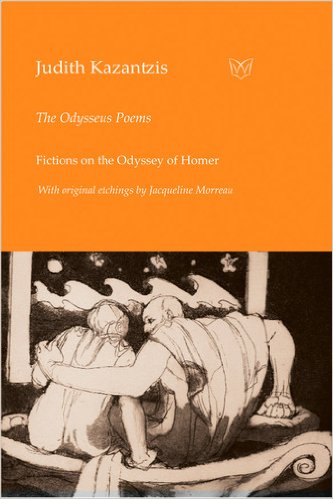

The Odyssey Poems. Fictions on the Odyssey of Homer

Homer’s epic has always prompted strong responses ever since its first appearance during Greece’s archaic period. Poets and playwrights ransacked it for stories in the later centuries BCE (Before the Common Era). The process continued through the European Middle Ages and the Renaissance, on through the various literary Augustan, Romantic, Victorian and Modernist periods, and right up to our own times. Sometimes this took the form of notable translations. At other times, writers interacted powerfully with Homer’s content. In recent times one thinks of Joyce’s Ulysses, Auden’s The Shield of Achilles, Derek Walcott’s Omeros, Christopher Logue’s War Music, Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad, and Alice Oswald’s Memorial, to name just a few of the best-known interactions with Homer. Judith Kazantzis’s suite The Odyssey Poems does not set out to appropriate epic form, as Virgil and Milton did in their time. Instead, this ensemble inhabits some of the key episodes from The Odyssey, in effect rewriting these as lyric rather than epic.

Homer’s epic has always prompted strong responses ever since its first appearance during Greece’s archaic period. Poets and playwrights ransacked it for stories in the later centuries BCE (Before the Common Era). The process continued through the European Middle Ages and the Renaissance, on through the various literary Augustan, Romantic, Victorian and Modernist periods, and right up to our own times. Sometimes this took the form of notable translations. At other times, writers interacted powerfully with Homer’s content. In recent times one thinks of Joyce’s Ulysses, Auden’s The Shield of Achilles, Derek Walcott’s Omeros, Christopher Logue’s War Music, Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad, and Alice Oswald’s Memorial, to name just a few of the best-known interactions with Homer. Judith Kazantzis’s suite The Odyssey Poems does not set out to appropriate epic form, as Virgil and Milton did in their time. Instead, this ensemble inhabits some of the key episodes from The Odyssey, in effect rewriting these as lyric rather than epic.

Spiritually, Kazantzis feels closer to Atwood than to any other of the forementioned authors, inasmuch as her rewriting can seem mischievous. Yet (as with Atwood) it is multi-perspectival; and angled in such a way as to articulate aspects of character and situation which, in Homer, are inexplicit. All the expected characters are present – Odysseus, Penelope, Telemachos, Nausikaa, Polyphemus the Cyclops, the Sirens, Kalypso, Aeolus – as are a number of famous encounters, such as Skylla and Charybdis, or the descent into Hades. But whereas Homer had presented these as autonomous people with their own lives and agendas, or as narrative events in Odysseus’s travels, Kazantzis treats them more as aspects of the central character’s psychomachy, or struggle with his own soul.

The Sirens will do very well to illustrate the tendency of the poems in this respect. Homer’s bird-women need sailors’ flesh or they don’t eat. But women and sailors’ flesh have another popular linkage that Kazantzis exploits. The siren-song, which was always in any case a come-on, is now a bid for business:

Like being tied up, sir? you seem

to like getting tied up. […]

Lick you, sir, any way you want?

Pour honey in those ears, clean out those

naughty ears? […]

Stuff that big fat mast down our throats?

[…] We can take it, oh yes, deeper … bigger,

bigger, oh … yes … YES … any way you want we do.

[…]Anything to please a passing fucker. Honey up yours.

Here, it isn’t the danger of the hero’s being seduced into becoming a literal meal that might hinder his return to his wife; but his own hedonism, a seduction pure and simple, and the offer of commitment-free hot sex. That is enough to send a reader back to the original poem, to wonder what may be going on between the lines. This note – of Odysseus fictionalising his long-delayed homeward voyage – is struck immediately:

Over the entire tale I think now

there brooded a monster uncontrolled

by reason or god.I could never describe

it to anyone, as if it sprawled

along my steering arm, a ganglion

steadily crooking my course.

The pathos of the sequence is not that of a homesick man’s thwarted reunion with wife and son. It is the sad spectacle of a conflicted self-deceiver who needs to dramatise, and externalise, his reasons for being dilatory.

Jim Stewart

Leave a Reply