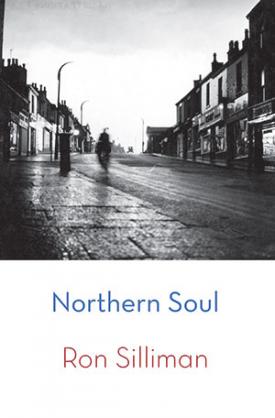

Northern Soul

Ron Silliman is an American poet with a distinctive voice and an extensive publishing history in poetry. Taken as a whole, however, his is a relatively meagre canon; he views his work as essentially consisting of several long poems spread over a large number of collections stemming back to the 1970s but which should be viewed as part of a larger whole. Many words, but relatively few poems.

Ron Silliman is an American poet with a distinctive voice and an extensive publishing history in poetry. Taken as a whole, however, his is a relatively meagre canon; he views his work as essentially consisting of several long poems spread over a large number of collections stemming back to the 1970s but which should be viewed as part of a larger whole. Many words, but relatively few poems.

Thus Northern Soul is the second in what he hopes will be a 360-poem cycle entitled Universe. His current rate of progress puts the completion of the work some centuries into the future, but every poet needs to set themselves targets. Northern Soul isn’t so much a “collection” as an unfinished fragment; the poem contained within its covers is formally consistent – over its 70 page length – with short lines of 4-5 words, no breaks or sections, nor any pauses for breath.

It’s a daunting read, but ultimately an enjoyable one: a travelogue of sorts, starting in Bury (a northern town famous for its black puddings) but journeying back and forth across the Atlantic to various locations – New Jersey, Manchester, Delaware and many other places – both recognisable and mysterious. The one location which stands out, however, is the nameless dreamlike existence of Silliman’s imagination, something which he acknowledges early on, describing how it is

Sweet sad

to awaken,

just when the dream’s

taken an erotic turn

your friend, without warning,

after all these years

to have opened her robe

the dress falling

just as you startle awake[.]

There are many such instances of the blurring of the dream and the real, serving to darken the work and to convey a sense of panic as the poem and its author hurtle along, out of control. The darkness is tempered, however, with nuggets of wit on every page. I particularly enjoyed his musing on

A daddy-long-legs bright orange

in the grass, those tiny

purple flowers so much larger

than he (how not

to assign gender)[,]

and also his wonderful insight on our conditioned response to narrative (possibly referring to the narrative he plans to extend across the centuries as part of his longer project)

Page 43

you will read

differently if

there are 94 to the book

than if there are just

What about

523 what then[.]

In parts, Silliman steps out of his flow, almost, to reflect on his poetic technique. This is a curious trick; although not entirely out of place given the monumental ambitions of the project, in the face of which most poets would question their worth. For example, on p.17

what I’m after

here is a tone

that is not

the vibration of phonemes

set into motion

but an emotion[,]

and on p.26

What occurs in the line

is itself prose

tho the line is not

How do I know

what I meant by that[?]

On p.41 Silliman again questions his own technique

Nobody gets

(me least of all)

the secrets

of the linebreak

and maybe even, in one of his dozens of references to birds he recognises the limitations of the form he has adopted

That one bird with

the same five-note song

over and over [.]

The sense of a work that can only ever be unfinished is evident towards the end, as the poet feels the pressure of age

what visit

will be my last

to survive is

to sneak past

all the traps [.]

Ultimately, the challenge of keeping pace with the headlong rush of Silliman’s style was too difficult for me; I yearned for the ebb and flow of narrative, the variations in tone and form which a more traditional assembly of poems brings. The fault is mine, however. Silliman’s triumph here is to show less what a poem should be and more what it can be.

Andy Jackson

Leave a Reply