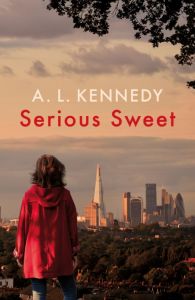

Serious Sweet (Longlisted for the 2016 Man Booker Prize)

A.L. Kennedy

(Jonathan Cape, 2016); hbk. £17.99

Dundee-born A.L. Kennedy needs no introduction, being extensively published in fiction, no slouch in non-fiction, and a respected commentator in various media. She sidelines as an acerbic stand-up comedian; all these abilities and honed forms of observation feed Serious Sweet. At the time of reviewing, this book has not made the leap from the Booker’s longlist to shortlist. Doubtless that’s disappointing for both writer and publisher; not having read the full list, I can’t judge, but my strong sense is that should not deter any reader. Serious Sweet works.

Dundee-born A.L. Kennedy needs no introduction, being extensively published in fiction, no slouch in non-fiction, and a respected commentator in various media. She sidelines as an acerbic stand-up comedian; all these abilities and honed forms of observation feed Serious Sweet. At the time of reviewing, this book has not made the leap from the Booker’s longlist to shortlist. Doubtless that’s disappointing for both writer and publisher; not having read the full list, I can’t judge, but my strong sense is that should not deter any reader. Serious Sweet works.

Ulysses-like, it’s set in a 24-hour space and for Dublin, find London; like Joyce, Kennedy’s writing is powerfully rhythmic and poetic, hymning a love song by exploring the processes of thinking in a way which is almost forensic, without any loss of written integrity. Justifiably typographically adventurous, the structure of this novel harnesses those passages of inner thought, and keeps a handle on her subtle plotting.

Superficially, a love story of two terribly damaged characters meeting after considerable correspondence might be stale. Being Kennedy’s protagonists, however, they don’t so much have baggage as several airport carousels, disgorging splitting luggage. Readers familiar with the writer will be aware of her italicised, very pure stream-of-consciousness monologues. Whilst such devices are not unique, what really impresses here is how nuanced these voices are. All too often in reading such passages elsewhere, I’m very aware of the writer’s undercurrents and voice, but less convinced of the characters’. Not here. The two characters dominate, but in their inner and their not always so very outer thoughts, there are four quite distinct, quickly unmistakable voices weaving the narrative, and sometimes these internal/external voices interact. Jon’s inner staccato, self-worrying feathering of ideas constantly self-corrects, trying to smooth his thoughts; outwardly his hands try to flatten his Savile Row tailoring. Meanwhile Meg’s equally nervous lack of self-belief manifests in a constantly undermining, yet occasionally gallus unspooling. Both characters exert a certain control in the non-italicised passages, and there is something impressively Jane Austen-like in Kennedy’s attention to idiolect, how it moves, develops in different situations and eventually interacts. After all, these characters don’t really cross until midway through the narrative, nor actually meet until significantly later.

That proportion of overtly unfettered troubled narration might go adrift in less skilful hands, but Kennedy fastens it to strong uprights in the form of significantly calmer, third person-observed sections, which not only set or gather in scenes, but also allow breathing space. I have no idea if Kennedy writes poetry, but her prose treads that thin line, suggesting she’d do it wonderfully. If that sounds heavily indigestible for a novel of more than 500 pages, then it should not; her humour paces through even the darkest places in the narrative.

“They smelt of Badedas and escalating fear.”

As well they might. Jon (or possibly Mr August, or Corwynn who “suffered from areas of sagging – afflicting both the trousers and the man”) and Meg (or Sophia), struggle under a great staggering of pasts and presents: illness, abuse, alcoholism (a subject often written well by the teetotal Kennedy) and a whole circumstantial disentangling. Jon’s outwardly respectable career with “Westminster’s distressed” covers shady dealings indeed, but these are both increasingly likeable, harmed people, struggling to make their necessarily compromised decisions in endangering environments.

There is no Molly Bloom level of ecstasy in their twenty-third hour, but there is – for Kennedy – an uncharacteristic surfacing of hope. I’m uncertain how much I would give to their relationship’s long-term prospects, but there is real optimism here.

Let’s forget the Booker. Dublin celebrates Joyce annually in Bloomsday; perhaps Dundee needs a Kennedy Day, where characters pop up at street corners, voicing her marvellous monologues to the unsuspecting. Unlike their Irish counterparts, they would be entirely contemporary and initially invisible. Perhaps in that caring listening, unravelling the unnoticed already among us we would have something of A.L. Kennedy’s essence.

Beth McDonough

Leave a Reply