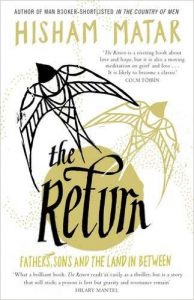

The Return (Shortlisted, 2016 Costa Biography Award)

Hishtam Matar

(Viking, 2016); hbk, £14.99

The country that separates fathers and sons has disorientated many travellers. It is very easy to get lost there. […] And the fathers must have known, having once themselves been sons, that the ghostly presence of their land will remain […]

The country that separates fathers and sons has disorientated many travellers. It is very easy to get lost there. […] And the fathers must have known, having once themselves been sons, that the ghostly presence of their land will remain […]

Hisham Matar’s debut In the Country of Men, was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize (2006) and more; his second, Anatomy of a Disappearance (2011), showed his was not simply a precocious flare. These fictional works began a necessarily obsessive literary journey now examined with clarity in this memoir.

New York-born of Libyan parents, Matar explores many dualities in The Return which tears, or tries to tear the veils that separate various paradoxes, duplicities and separations. In a childhood spent between Tripoli and Cairo, very sinister adult shadows began marking Matar and his brother Zaid, even in the calculated “safety” of their Swiss and English schools. Already, they owned double lives.

Central to the narrative is Libya’s presence and absence in the writer’s life, and most specifically the existence and disappearance of his beloved father, the writer and activist Jaballa Matar who was abducted by Qaddafi’s agents in 1990 when his son was 19 years old. Hishtam Matar’s sustained, courageous investigative work is a matter of open record but there is still no certainty about Jaballa Matar’s fate. He was last known to be alive in Tripoli’s notorious Abu Salim prison – that ironically dubbed “noble palace”. It is reasonable to believe he perished there, on the 29th of June 1996, when Qaddafi’s brother-in-law and closest aides directly instigated the assassination of 1,270 men. If so, for reasons clarified in the book, no physical trace of him can ever be found.

The Return opens in Cairo airport’s departure lounge, then switches between countries, times and tenses, outlining the writer’s search; Matar writes, “My father is both dead and alive. I do not have a grammar for him” and “I envy the finality of funerals. I covet the certainty”. Matar’s father’s kidnap follows quickly after the death of his own very aged grandfather; this connects and explores binaries concerning contradictions and challenges for the writer’s filial love. We note too the patterns in the grandfather’s own earlier dissidence: “History remembers Mussolini as the buffoonish Fascist, […] but in Libya he oversaw a campaign of genocide.”

Matar’s words are sometimes lyrical, elsewhere clipped; his use of metaphor beguiles, just as the graphic (but not gratuitous) nature of violence in other paragraphs shocks. Though his writing delivers documentary evidence when required, it also threads a (secular) Islamic beauty with an almost ghazal-like quality throughout (even though his literary references are paradoxically almost exclusively Western – Telemachus, Hamlet and more). That Koran-based cultural underpinning is also there in the book’s figurative imagery. Meeting at a real table, Matar notes: “To make up for the missing pillar, the once balanced structure of four columns was now in perpetual strain.”

Colm Tóibín describes this intensely personal memoir as “a moving meditation on grief and loss.” It is as resonant as it is jewel-like. Matar’s work is translated into 29 languages, but you will struggle to find any editions sold openly in Benghazi. As Syria’s tragedy unfolds (and these intertwined countries’ connections are written overtly), this is both a page-turner and a contemplative work. It is impossible to miss echoes of what Europe has done to and not for these lands. Matar’s documented contacts with senior U.K. government figures will chill with their duplicity, inappropriate humour and dark manipulation. Equally shockingly, a respected African statesman’s choices will haunt…“even a man as great as Nelson Mandela felt too indebted to Qaddafi to risk upsetting him.”

Whatever news we piece from the BBC, newspapers, even Al-Jazeera, likely we are still too ill-informed to understand Syria’s tragedy, or Yemen’s, or Libya’s … but this land in between, revisited 36 years after Matar’s departure, casts many kinds of light on matters personal and universal. This is a fitting, brave testament to Matar’s father, but its importance for us all is that it manages to be simultaneously globally relevant without losing its poignant intimacy.

Beth McDonough

Leave a Reply