Leásungspell

Hwæt!

Hwæt!

Whether you take that iconic, still-contentious word as an exclamation, an exhortation, or accept Heaney’s gently Hibernian “So”, whatever aspects of the Anglo Saxon epic you unravel in Leásungspell , from the first Bob Beagrie alerts you that all is not as it seems.

Huisht, lads, haad ya gobs [.]

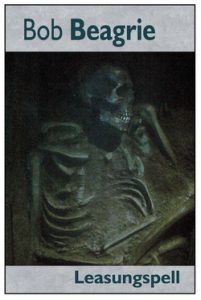

Set in Northumbria, 657 AD, Leásungspell (“a tale, fool’s tale, fable or fiction”) is in many ways at least a three-way hybrid: in its narrative, its setting and most quickly, in its language. As we follow our hero monk Oswin through trails and trials, we are always in the heartland of change, where past, present and future collide and challenge. Paganism, magic, Roman and Celtic Christianity interlace, in a tale which is an epic, and “also an anti-epic […] small tale of a nobody wandering alone through the Dark Ages.”

Bookended by a modern English prologue and epilogue, that first line gave the game away. Whatever scholarly debts Leásungspell acknowledges – Beowulf, Y Gododdin, all those scops and healing women (The Charm of the Nine Herbs in particular) – this is far from simply a cod-Dark Age epic. Certainly, there is a “clashing of broadswords” vibe, but in that crash of consonantal clusters and kennings there is also a subliminal thrash of electric guitars. Linguistically, it fuses Anglo Saxon, modern English and northern dialects. That very Geordie opening is not, in truth, particularly typical of the language, but in that rather more accessible language’s very separation from the main body’s density works very like the rallying call to listeners usually heard in hwæt. Periodically, that contemporary presence rears again, alerting the reader that all is not past by any means. “Godspell” for example is surely not there solely for first millennial purposes.

If poetry has to be read aloud to live, then that is particularly true here. Leásungspell is a ripping yarn, with page-turning tales within tales, potions and blood; it must be chewed in significant chunks to keep Beagrie’s linguistic broth bubbling … a recipe which is, after all, his own. Words like “glöm” are neither the contemporary “gloom” nor quite as the Anglo Saxons would know them. Helpfully the poet has offered a glossary, albeit thankfully resisting any temptation to over-gloss. Though there were odd words I struggled to discern (though it is surprising that a word like “thole” merited translation), in the main the powerful alloy of reading aloud and context will suffice for the tuned-in reader.

There is a feeling not only of northern England, but of the continuing North Sea countries’ saga traditions, just one of the many linguistic delights is Beagrie’s careful layering. You will note echoes of contemporary Geordie, Old Norse, Shetlandic and Icelandic in your reading, and respond to how the poet has separated the language of charms here, into something far closer to Anglo Saxon, effectively giving it a needed contextual archaic quality. One of the most charming passages unpicks Oswain’s surprise hearing an apparently doughty woman having a goodly dismissive snigger at the older ways. Leásungspell is not all a Blotmonað of pierced bone cages … those charms and songs pace the narrative effectively, as do the natural history descriptions. If occasionally there’s the merest knowing whiff of cheese, there is also:

I pluccede beries, feldswam, wyrt, root and nut.

ciewed netel, mallow, tickled troot, grubbed [.]

The glossary includes a plethora of older-named real places. I suspect this could be better-served by the book’s design – the kind of maps which lead readers through Tolkien’s imagined lands, and which plot Hardy’s Wessex would be a boon. Similarly, explanations of the various historical figures might also have been placed elsewhere. These are minor matters in a “visionary” poem, which the book itself suggests is best experienced with the accompanying soundtrack. Indeed Leásungspell calls for intermedial interpretations. Hwæt! I had no such luxury! I shall repair to the Mead Hall now to hear a work both fersc and mint.

Beth McDonough

I am regular reader, how are you everybody?

This article posted at this site is truly good.