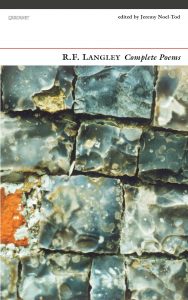

Complete Poems

Roger Francis Langley was a Warwickshire-born poet, as well as a close friend and contemporary of avant-gardist J.H.Prynne. Complete Poems is a summation of his writing spanning a relatively short career – from 1994’s Twelve Poems to his final collection The Face of It, published four years before his death in 2011. His poem, “To a Nightingale”, received the Forward Prize for the best single poem in 2011.

Langley’s poetry is often concerned with small things; the beating of tiny wings, the movement of leaves, the subtleties of gesture and expression, whether human, animal or botanical. At times, reading this collection felt like being with the poet on a field-trip; waiting, observing, recording, analysing and then recounting. The poems are precise, sharp and engaging, and although they can largely be categorised as “nature poems”, they are not just observational but contextual, with Langley’s own role in the writing and observational process often forming part of the lyric, serving as emotional field notes or personal annotations on sketches or photographs. In “Mariana” the poet observes a woman as she herself observes the beating of a Martins’ wings;

she

might have soon discerned her

self, seeing them. Not things,

but seeing things. And with

such care, it would be like

being shown what was not there.

The final line from the excerpt above seems to identify the underpinning philosophy of Langley’s work – it is “with such care” that he works through his method.

Stylistically, “Mariana” is a good example of the way Langley often works within his poems – short stabs of language punctuating deeper and more loquacious observations, the combination of which serves to break up rhythms in places, and occasionally give the poems a disjointed, disturbed feel, as evidenced by “The Long History of Heresy”:

Some folded

leaves. Some pierced. Others eaten

to the veins. The flies, in silhouette

moving about the memoirs. So deep

into the book. Improbable fiction.

Old smears.

This “poem-as-field-note” technique is never far from Langley’s pen, but is most consciously resolved in the poem which became his most successful, albeit posthumously – “To a Nightingale”.

A chiff-chaff. Purring of two

turtle doves. Voices, and some

vibrate with tenderness. I

say none of this for love. It

is anyone’s giff-gaff. It

is anyone’s quelque chose.

No business of mine. Mites which

ramble. Caterpillars which

curl up as question marks.

It is sparse yet meticulous, with rhyme hovering gently around it, pausing to alight here, there. Always delicate and considered, it is a fascinating pleasure on the page and in the mouth. Interestingly, an introductory note on technique by Langley himself is featured – a rare inclusion in a collection of poetry – and in this note he reveals something of his insecurities and uncertainties, as well as his technical approach:

I don’t write many poems, so each one has to be able to keep running, faster than I can, for as long as possible.

Langley’s pursuit of richness and his layering of meaning, while retaining an economy of words, is given full justification; he goes on to describe what Wallace Stevens called “the loneliness of thinking” – clear introspection which he possibly finds painful or difficult, but utterly necessary to his process. Langley revels in the “shocks of fear and joy” of specific moments, moments that both the poet and the reader constantly seek.

The editor notes Langley being taken by a preface from a guide to British spiders published in the 1980s. He notes how the discovery of a drawing or description of a find yields the excitement of someone “having been there before”. Perhaps Langley’s gift is to pass on the certainty that when we try to record something observed in nature, he (among naturalists, artists and poets across centuries and continents), has been there before, and tried earnestly to do the same.

Leave a Reply