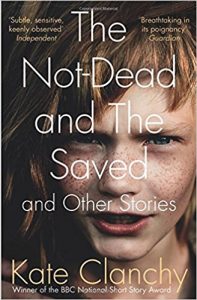

The Not-Dead And The Saved (And Other Stories)

From the very start of Kate Clanchy’s The Not-Dead And The Saved (And Other Stories), we fall straight into her powerless mess of human nature responding to a power-hungry, often pessimistic world. Clanchy’s collection of short stories considers various forms of motherhood in respect to personal development. Through dimensional, flawed characters, and with notable proficiency, she repeatedly builds the mother figure upon responsibility rather than biology .

From the very start of Kate Clanchy’s The Not-Dead And The Saved (And Other Stories), we fall straight into her powerless mess of human nature responding to a power-hungry, often pessimistic world. Clanchy’s collection of short stories considers various forms of motherhood in respect to personal development. Through dimensional, flawed characters, and with notable proficiency, she repeatedly builds the mother figure upon responsibility rather than biology .

“WILL DALE SEE MUM? shrieked the papers next, and Dale said no, no thanks.” In her first story “The Show,” Dale, rising teenage rock-star meets the birth mother who abandoned him as a baby for the first time. Immediately, there is a disconnect between the “woman” and her son. Clanchy, with finesse, implies that Dale’s inability to connect with the female sex can be attributed to the absence of his mother during childhood. Accordingly, the final scene in “The Show” finishes with Dale alone in a room with dominating male figure The Big Star.

The next tale takes a new twist on Clanchy’s theme. “Irene,” a mother who has failed as a maternal figure redeems herself as a grandmother. In the process, she admonishes her daughter, the narrator, for similarly falling prey to the cycle of detachment from her child. Here, she states: “A mother’s the woman who does the work […] Does the night feed, boils the clothes.” Irene’s return in old age inspires the disengaged protagonist to interest herself in the needs of her baby.

A personal favorite from the collection, “Black Bun” transcends the traditional view of motherhood; firstly, through the dialogue between a wife and her mother-in-law; and secondly, through the focus on an adopted son and his familial bonds. “Aunt Mirrie and the Child” also addresses a surrogate relationship between an integral caretaker and an orphaned niece.

“Brunty Country” uncompromisingly depicts another aspect of motherhood: legacy. It is a clever tale about an aspiring literary critic, who, upon reading a “hand-bound, hand-sewn, looney book of poems” seeks to find its author, Ellis Bell, in the vast countryside of Leeds. Eventually, she realises that Bell is in fact Elizabeth Brontë, a novelist from the early 1800s whose role in this short story is solely to represent her legacy in the literary world for future female writers.

Other tales discuss Clanchy’s theme by emphasizing a lack of maternal presence. In “The Invention of Scotland,” Clarissa is a passive mother who eventually loses the respect of her daughter Ophelia.

The Not-Dead And The Saved (And Other Stories) offers shades of James Robertson’s Republics of the Mind. Both are filled with stark, spontaneous voices staggered across generations. Scottish to the core, they draw upon their cultural heritage. In “Irene,” Clanchy rewrites the renowned nursery rhyme “You cannae shove yer grannie off a bus.” Evidenced in their short stories, both authors believe that growing-up is a continuous process; consequently, the ages of their characters do not necessarily determine their level of maturity.

Balancing between points of view, Kate Clanchy’s collection is a mixture of perspectives where motherly figures, whether conventional or atypical, are characterized by commitment to their role. Despite its focus on maternity, this selection of short stories analyses emotions that translate effortless across all ages and genders. The Not-Dead And The Saved (And Other Stories) considers motherhood with a beautiful blending of comedy and calamity.

Leave a Reply