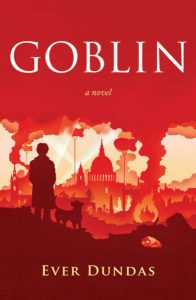

GOBLIN

Histories of the 20th century are numerous and, for those of us interested in understanding the present moment, fascinating. There is a commonplace schoolroom telling of developments, wars and upheaval, but there are also endless personal stories: journeys through the recent past that bring more emotional engagement to their setting, or look directly at events that might have slipped from the collective memory.

Histories of the 20th century are numerous and, for those of us interested in understanding the present moment, fascinating. There is a commonplace schoolroom telling of developments, wars and upheaval, but there are also endless personal stories: journeys through the recent past that bring more emotional engagement to their setting, or look directly at events that might have slipped from the collective memory.

Winning the Saltire Society’s First Book of the Year prize, Dundas gives us Goblin: a girl born in 1930, surviving London’s Blitz through World War II, who grows to be an elderly woman living in Edinburgh, in 2011. The War provides both an initial setting for the novel, and a central frame for much of its historic plotline, with attention returning to that time even when life has moved beyond it. Goblin grows from eight years old, to sixteen by the end of the War, and then onwards into adulthood, travelling through Europe. Our continual exposure to her autobiography continues well into the 1970s, balanced against a retrospective anchor as the story is written down in the 21st century with both narrator and reader firmly looking back, trying to make sense of past events.

Throughout, Goblin gives us a first-hand version of its titular character’s life, firmly embedded as it is in her point of view. The narration switches frequently between these ‘past’ and ‘present’ versions of the character, and Dundas handles this with precision. When writing in 1939, the narrative voice reads as a child’s; as a young woman the language evolves suitably, and then again to match Goblin the octogenarian storyteller. The childhood innocence can be beguiling, but a reader should not take the youthful nonchalance and starry-eyed affection as a sign that passionate grief and romance will not come later. This is also not to say that the character herself is inconsistent: Goblin’s passions, tendencies and priorities evolve fluidly throughout the novel, so that the reader can subtly track each quirk and foible as it comes into place.

The narrator is creative and tricksy, to the point of being unreliable. Revisiting London in 2011 recalls childhood fantasies more vividly than reality, blurring the present with almost Clive Barker-esque spectres and obscuring witnessed events. Memory, repression and trauma make up core themes – Goblin’s mantra of “let the past stay in the past” is regularly challenged, but since the reader is bound to a single storyteller, the past itself is held tantalisingly out of reach until the final chapters of the book. When it comes, it hits hard, and we are given a staggering climax to the untying of the novel’s great emotional knot.

Other themes flicker through the story: the mutability of identity, and the importance and impermanence of relationships and family. Our narrator’s defining external features shift, especially in her youth. She disguises her gender, takes on different names – the one “on her birth certificate” never being revealed. Across the years she has a Ma and Da, “pretend parents,” a Mum and Dad, a Grandma, and a string of romantic partners. Relationships are important to the book, but I would guess that half the named characters are non-human. With Goblin being Dundas’s debut novel it is hard to comment, but I suspect her passion for animal rights might become her leitmotif. The personality, but also the tenderness Goblin’s ever-evolving menagerie are given, suggest this is a matter close to the author’s heart, as well as the characters.

Goblin, then, is a deeply personal work, but one written with great finesse, especially for a first-time novelist. It provides a nuanced examination of the past, and how we should bring our memories forward into the present. With clearly drafted ideas and a talented use of language, Ever Dundas’s career may have just begun, but it will definitely be one to follow.

Leave a Reply